Punjab, the land named after its five rivers, is today reeling under the devastation caused by those very waters. For more than two weeks, the state has remained in the grip of floods of an intensity unseen in recent years. The Ravi has overflowed in the border districts, while the Beas and Sutlej, swollen with monsoon rains and water released from dams, have submerged vast tracts of Majha and Doaba. Malwa too has come under severe threat, with smaller rivers and canals breaking their banks and causing immense destruction. Homes, crops, livestock, and entire means of livelihood have been swept away, leaving thousands homeless and destitute.

Although floods are natural disasters, the full weight of this calamity cannot be attributed solely to nature. Human errors and administrative negligence have compounded the destruction. Floodgates left unrepaired, delayed releases of excess dam water, and the lack of adequate preventive measures have aggravated the crisis. Technical shortcomings, if rectified in-time, could have minimized the scale of loss. The Indian Army has on countless occasions demonstrated its efficiency in disaster management—building bridges within hours and providing rescue operations during floods in Himachal, Uttarakhand, and Jammu. Yet in Punjab, questions arise as to why such swift measures were not mobilized with equal urgency. Amidst this devastation, one truth stands tall: the indomitable spirit of the Punjabi people. History bears witness that whenever Punjab has been scarred by foreign invasions, political upheavals, or natural calamities, its people have turned to one another for strength and stood upright in resilience. This strength is not accidental; it is deeply rooted in the Sikh spiritual tradition of Chardhīkalā—ever-rising optimism, fearlessness in adversity, and an unwavering commitment to humanity.

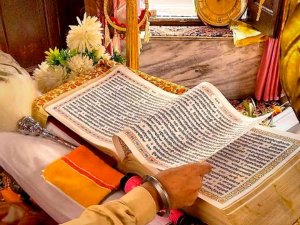

From the days of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, who proclaimed the essential unity of humankind, to Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, whose supreme sacrifice epitomized courage in the face of tyranny, the Sikh tradition has nurtured resilience as a moral and spiritual discipline. In the midst of floods today, this tradition is visible once again. Gurdwaras have opened their doors for shelter, the langar continues to ensure that no one sleeps hungry, and countless Sikh organizations and volunteers are wading through floodwaters to deliver food, fodder, clothing, and medicines. This is seva, selfless service, carried out not as charity but as a duty—an expression of the Sikh principle “sarbat da bhala” (the welfare of all). Equally moving is the sight of ordinary villagers, who despite losing their own homes and fields, are reaching out to save their neighbours, feed stranded cattle, and carry survivors to safety. Such acts recall Punjab’s age-old collective consciousness that has seen the people through Partition, wars, and earlier natural calamities. Even in personal loss, Punjabis find the courage to uphold others—a living testimony to the doctrine of Chardhīkalā.

The present calamity also raises troubling questions about governance. Successive state and central governments have often treated Punjab as a frontier to be defended or a granary to be harvested, but rarely as a society to be nurtured with empathy. Even today, many Punjabis feel alienated, as if “Delhi is far” despite physical proximity. Relief measures remain slow and inadequate, and the silence of many national institutions has been painful. Yet, in the absence of external support, Punjab once again proves to itself and to the world that it does not wait passively for rescue.The Sikh ethos has always taught that dignity lies not in lamenting fate but in actively shaping one’s destiny. The floods are devastating—fields are ruined, homes collapsed, diseases spread by stagnant waters loom large, and rebuilding will take years. Yet, in the Sikh worldview, adversity is never final defeat. Guru Gobind Singh Ji, when faced with immense personal tragedy, gave to the Khalsa the mantra of Chardhīkalā, urging his Sikhs to rise even higher in spirit during their darkest hour. That very legacy is visible in today’s Punjab, where instead of surrendering to despair, communities are rediscovering bonds of brotherhood, standing shoulder to shoulder, and transforming suffering into solidarity.

It is equally important to recognize the broader national responsibility. Punjab, which has for decades been the breadbasket of India, deserves not neglect but solidarity from every quarter. The floods are not Punjab’s private tragedy but a national calamity. The open-heartedness of Punjabis has always been well known; a small gesture of compassion is remembered and cherished by them for generations. This is the moment for governments, institutions, and fellow citizens to show Punjab that its pain is the nation’s pain.

Three and a half centuries after Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji’s martyrdom, his message rings with renewed relevance. Sacrifice, courage, and the defense of human dignity define the Sikh spirit. The people of Punjab will rebuild their lives, as they always have, but the measure of our humanity as a nation will be judged by whether we stand with them now.Punjab today is wounded, yet unbroken. Its fields may lie under water, its homes in ruin, but its people continue to embody Chardhīkalā—undaunted, compassionate, and ever-rising. The floods may test the endurance of Punjab, but they will never wash away the resilience, generosity, and spiritual strength that have always defined this land of the Gurus.