How an Amazonian Tribe Is Mastering the Modern World

Part 2: Two Worlds

It takes an hour to drive back in time from one world to another.

It takes an hour to drive back in time from one world to another.

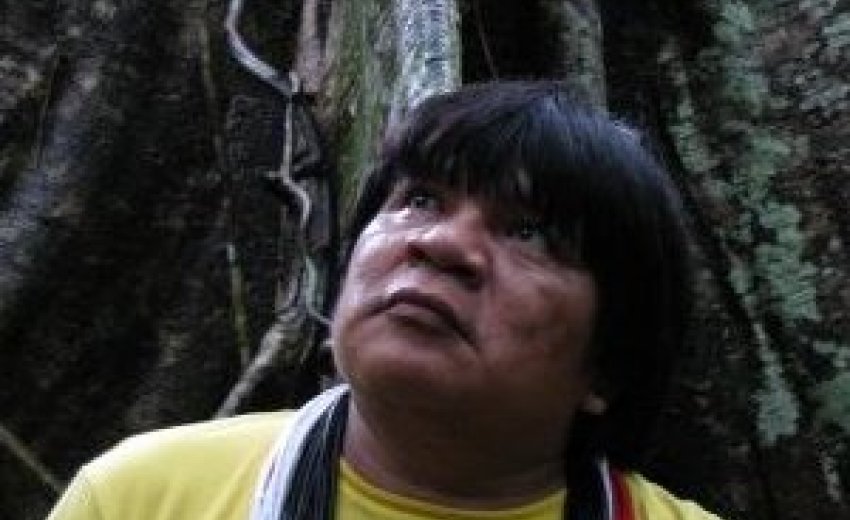

In one world Almir Surui has two wives, one in Cacoal, the other in Porto Velho, as well as five children, a house with a garden and a dachshund. In this world he is something akin to the foreign minister of the Amazonian Indians. He has traveled to 26 countries, been at the United Nations in New York, taken part in the Copenhagen climate summit, and had an audience with Prince Charles in London. Al Gore intends to pay him a visit in the near future. In December the Brazilian magazine Época named him as one of the hundred most important Brazilians, together with soccer star Kaká, model Gisele Bündchen, and writer Paulo Coelho. He is a member of two government commissions, and during the elections in the summer he will be standing for a parliamentary seat as a member of the Green Party.

His other world is Lapetanha, the place of his birth in the reservation, the village where he was elected chief at the age of 17 because his father had been a chief before him and perhaps also because they sensed that he was somewhat special. In this world, the people eat grubs and only got electricity four years ago. Here he paints dots and lines on his face and body during religious festivals, the remains of which can be seen as faint blue coloring shimmering on his skin.

This is the world which was rocked by modernity 41 years ago when workers cleared a path through the forest as a prelude to the construction of a highway. This road brought with it settlers, cattle, cars, and telephones. Today, in many settlements you can find a chest freezer in which the villagers put the peccaries they hunted with bows and arrows.

Lost Harmony

This other world begins at the end of the fields where the forest suddenly grows dense again. Only a narrow track leads to the village comprising a few huts, a school, a church, three computers, and 102 inhabitants. Almir Surui parks his pickup outside the wooden house of his parents. Marimop, his 87-year-old father, is lying in a hammock wearing a green crepe shirt and orange shorts. His mother is squatting on the ground drilling holes in an armadillo shell.

Both have two blue lines across their face. Almir's father explains that it is the symbol of the Surui, and that all men and women used to have this tattoo. "But young people don't want that anymore." I ask him what has changed since his people were involuntarily connected to the outside world. "The spirits used to keep the forest and the weather in harmony," the old man explains. "But the spirits are no longer what they used to be in the time of great tranquility." In other words, before 1969.

The loss of tranquility was accompanied by a loss of tradition, primarily pride. Outsiders sneered that the Surui were stupid and indolent, and they became embarrassed to call themselves indigenous people. Since then they have been at pains to appear as Brazilian as possible. Whenever they travel to the city, they wear carefully ironed shirts and meticulously polished shoes. Those who can afford to tile their terrace. A handful even own a car. And the most important person in the village is no longer the shaman, but a man from Germany. Every Wednesday, the missionary comes to the village to preach -- though mostly about the Apocalypse and Genesis because little else has been translated.

Looking at the chief sitting between his parents, you can imagine what a huge leap he must have taken to venture out into the other, alien world. Almir was the first Surui to go to college. He studied biology in Goiâna, a city of 1.2 million inhabitants, where fellow students ignored him because he didn't talk, look or eat like they did. Almir only ate soft-boiled meat, preferably pork, and no vegetables or sauce. Although the Surui have adapted in many ways, their nutritional habits have not changed.

Technology and Tradition

The young Surui therefore sought refuge in the Internet and joined the battle against the World Bank and its Planafloro development project, which envisaged building new roads, dams and settlements on Indio land, but ignored the country's indigenous people. The Indios took on the World Bank -- and won. When the chief returned to his village, he brought with him a computer and an idea: that the Surui's only hope for survival lay in combining the two worlds of technology and tradition. It was the dawn of a new era.

|

|

| Juliane von Mittelstaedt / DER SPIEGEL In one day he generated 49,600 hits. He has five different e-mail addresses, and 324 friends on Facebook. |

Almir Surui, the Indio from the Amazon rainforest, is now famous.

It all began in 1997, the year of the Kyoto Protocol. Almir Surui was 22 when he hatched a 50-year plan that was as simple as it was ingenious: The Surui would themselves heal the wounds the loggers had inflicted on their reservation. And within 50 years their forest would be as pristine as it once was. Almir believes this is the tribe's only hope for survival because there had always been some Surui who would cooperate with the logging mafia, some to escape poverty, some out of sheer greed.

* Part 1: How an Amazonian Tribe Is Mastering the Modern World

* Part 2: Two Worlds

* Part 3: 'An Email from the Heart of the Rainforest'

* Part 4: Forest Could Vanish by 2100