|

| Jill Ruitenberg, president of design firm Ruitenberg Lind Design Group. - (ANJALEE KHEMLANI) |

The 15th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks holds a different significance for Sikh Americans: It also marks 15 years since they became a target of unprovoked violence.

Balbir Singh Sodi, a gas station manager in Mesa, Arizona, was shot and killed just four days after the terrorist attacks. His assailant was upset about 9/11 and told a friend he was “going to go out and shoot some towel-heads.”

It was just the first of many similar violent attacks on Sikhs at gas stations, on streets and at Sikh temples across the country.

Despite Sikhs having a presence in the country for more than a century, they have only recently been seen more visibly in the public eye.

“When Sikhs first came to the U.S. over 100 years ago, most people thought they were Hindus,” said Simran Jeet Singh, a religions professor at Trinity University and Sikh Coalition senior religion fellow. “Now, they think we are Muslims. Our community has constantly been trying to identify itself as an independent religion.”

A mass shooting of Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012 — more than a decade after the attacks — was probably the first time mainstream America was aware of the problem, Singh said in a phone interview last week.

Since then, efforts by individuals to create awareness and increase education about Sikhism have been on the rise to combat the prejudice faced by the community.

Take, for example:

- Kamaljeet Kalsi, the first Sikh American in the U.S. Army to be allowed a turban after their use was banned by the military in the 1980s.

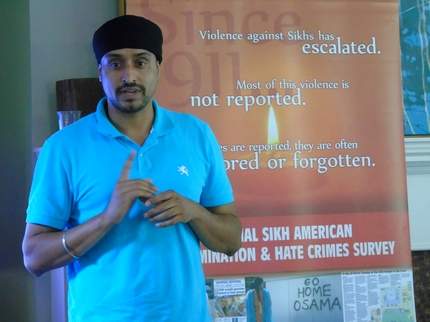

- Gurv Shergill, who is fighting for Sikh police officers to be allowed a turban while serving in the New York Police Department.

- Waris Ahluwalia, a fashion designer and model who was kicked off a flight in Mexico for wearing a turban

There are also a handful of organizations around the country trying to fight prejudice.

But, too often in the past, Sikhs ended up preaching to the choir — that is, speaking to members of their own community.

Singh said that is because Sikhs “don’t have a practice of really going out and tooting our own horns. The entire Sikh belief system is to get rid of your ego and pride, and it’s not in our nature to go out and talk about ourselves.

“Our tradition is to have conviction internally and do a good deed. There’s nothing in our DNA that tells us we have to go out and tell people about ourselves.”

The most vulnerable population within the community is the older generation, especially those who don’t speak English well.

“I was born and raised here and speak English. I’m speaking from privilege and can access resources,” Singh said. “But that’s not most of the community. I think about this a lot. We don’t have a concept of ourselves as victims. There is no word in our language, and we don’t think of ourselves as victims.”

Dr. Jaideep Singh, a historian and co-founder of the Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund, said many members of his community don’t realize the avenues available to them to report verbal or physical attacks.

For example, Sikh Americans who are born in the U.S. and speak English well can call a real estate agent to see an apartment. Before showing up, the agent will say it’s available, but as soon as the Sikh individual shows up — with his turban and beard — the agent will say it has been rented, Singh said.

“That’s the type of racism our community (sees),” he said. “And most of us don’t even realize we have a right to contest that. So we need to change that.”

Singh spoke to a group of mostly Sikh individuals in Skillman last week at the home of Jill Ruitenberg.

For Ruitenberg, Sikh turbans are the opposite of terrifying.

“If I see a Sikh person, I automatically know that I’m safe,” Ruitenberg said.

Ruitenberg, president of design firm Ruitenberg Lind Design Group, said her introduction to the religion was through Fortis Healthcare CEO Bhavdeep Singh. She said that, in April 2015, he invited her to the Glen Rock Gurudwara for a holiday celebration and, there, she fell in love with the Sikh religion.

The Indian hospital executive is a friend of Ruitenberg’s husband, Paul.

Since then, she has gained many Sikh friends and considers many of them her family, she said.

|

| Gurv Shergill is fighting for Sikh police officers to be allowed a turban while serving in the New York Police Department. - (ANJALEE KHEMLANI) |

She began to quietly learn about Sikhism from the internet, and recalls how much of her time searching landed her on sites that discussed the violence and prejudice faced by Sikhs in the U.S.

She plans to officially convert to Sikhism in February in India, and also now goes by the name Jagjeevan Kaur.

Ruitenberg was born Jewish, and was bullied as a child, which is why she said she understands the importance of standing up to hate crimes and prejudice against a community.

Simran Jeet Singh said the attitude that Sikhs have historically had about microaggression, and the reason behind a lack of reporting on it, is because it is seen as too much of a hassle.

“Like a fender-bender,” he said.

Meanwhile, Ruitenberg has invested in helping Sikh organizations thrive, in hopes of helping Sikhs become more visible.

She offers to make signs for free for Sikh charities and temples.

“I want Sikh businesses to spread. It’s important,” Ruitenberg said.