|

The last woman standing | ||||||||||

|

“She is worth more than all the soldiers of the state put together for any purpose of mischief,”

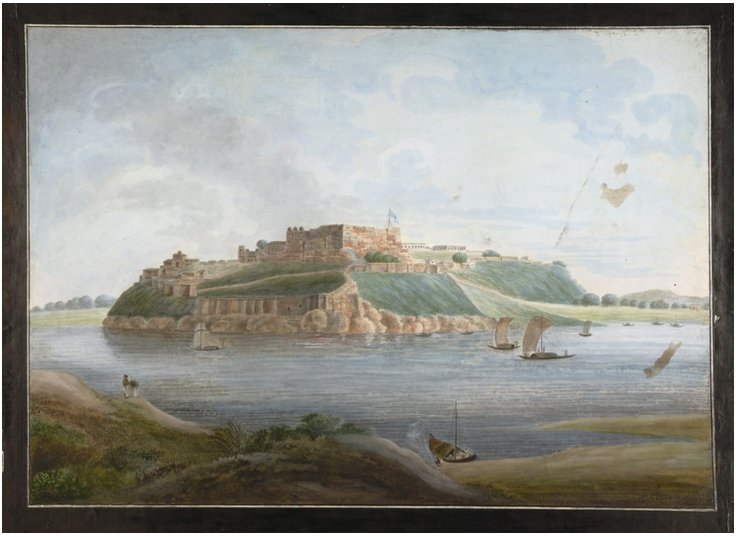

Here she was, a bewitching beauty, imprisoned in a high-security fort, secluded from everyone. “This lady is dangerous”, the guards were told and she was under constant watch. Almost two years had passed since she was incarcerated in this dingy corner of the fort. She had been losing her famed beauty and charm. But the lady! She was not one who would give up. She gradually endeared the guards with her stories. So much so, that on her pleading, she was permitted a maid that brought her fresh supplies of clothes and fulfilled her small indulgences like a massage, cleaned her dishes and brought her baskets of fresh fruit from nearby villages across the Ganga. The days used to pass in solitude with the solitary maid helping her with her chores as the guards switched duties behind the imposing walls of the impregnable Fort Chunar. Fort Chunar, fourteen miles south of Benaras, stands on a rocky bluff rising above a meander in Ganges and offers a vantage position for defence. The rocky face of the fort is impregnable due to its steep slope on one side and the mighty Ganga on the other side. Many crude cylinders were stored in the fort area to roll them down over any army of enemy soldiers attacking the fort. Most of the enclosed fort area consisted of plains overgrown with grass and a few trees.

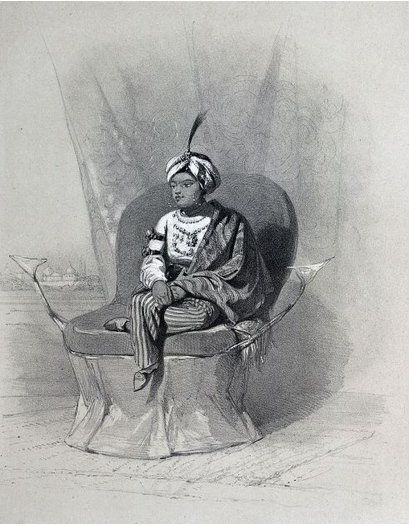

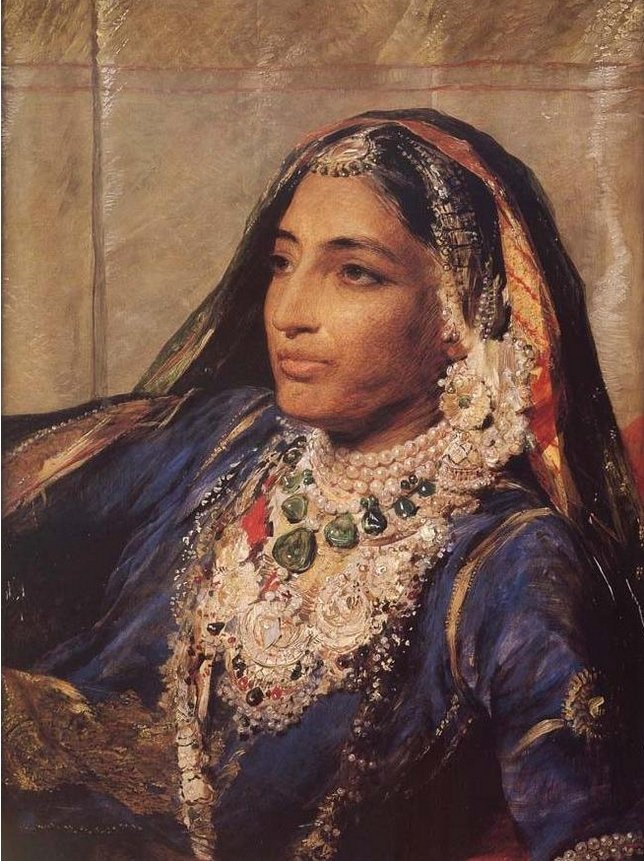

The British rulers accorded her small mercies and comforts though, of her own maid, and of wearing her large collection of jewellery. After all, she had once been a mighty empress! The empress of an independent nation larger than Germany and France combined. She was the widow of the mighty emperor who the British never dared to attack as long as he was alive, decades after they had won all the remaining princes and kings of India. Her emperor’s favorite queen and renowned for her beauty, she was widowed in her twenties.

After the death of her husband, the palace intrigue had been too much to handle and after the death of her step-son, she had to wriggle through many in-house machinations to hoist her 5 year old son on the throne; with herself as the Queen Regent and de-facto ruler. For around five years she had held control of the reign. But the British had become quite intrusive and had kept on attacking her kingdom. Finally they had managed to usurp her son and in a forced treaty had annexed her kingdom. The king had been sent to Britain and she had been imprisoned. Before being imprisoned in Chunar , she had been imprisoned at Sheikhupura near Lahore and at Varanasi and at several other places. At all places she had found a way to send secret messages or letters to her followers and friends spread across India.

In the middle of the night that day in Chunar Fort, she wrapped herself in the poor maid’s khadi sari while decking the protesting woman in her maharani garb, bejewelled and all, and left her in the cell shivering from fear while she veiled herself and walked out to her uncertain future beyond the walls of the fort, stealthily slipping out to the river.

The nearest independent kingdom was Nepal, 800 miles away. Her faith made up her mind to go there. She trudged on foot, all alone, slowly making her way out of the British Empire, through swollen tributaries of the Ganga and thick forests in the Himalayas. There is little record of how she made the long treacherous journey. But one fine day in April, 1849 she turned up at the court of the Prime Minister of Nepal – Jung Bahadur Rana, who having imprisoned the king was in fact the de-facto King of Nepal. Tattered and bruised she was, but the commanding voice with which she addressed Rana was enough to convince him that she indeed was who she claimed to be. She indeed was the Queen herself. The Queen – Maharani Jinda, the erstwhile empress of Punjab, the wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, once the possessor of the famed Koh-I-Noor diamond, the widow who had wielded great power as Queen Regent to her son, Maharaja Dileep Singh of Takht Lahore, Punjab. She had commanded armies against the British, as queen of the Khalsa forces. Her army was the last to fall to the British, almost a decade after they had won over the rest of India. During her regency, her army generals had treated Jinda with deference and addressed her as Mai Sahib or mother of the entire Khalsa Commonwealth. Leaving aside the traditional veil she had held court and had run the empire successfully.

In fact, a treaty had been signed with British and her powers were curtailed. But, the British found her too hot to handle, and on the charge of treason, she was arrested by the British and her son, the last independent ruler of India, Maharaja Dileep Singh was packed off to Britain. The British were too afraid to let her off like they had other erstwhile princes and royals with pensions.

So, she was in Nepal now after the escape from Chunar. It goes to the credit of the Nepalese that they gave asylum to the queen. She was given royal treatment in fact, a seperate quarter, royal trappings and a generous hospitality. Jung Bahadur gave permission to build a small Gurudwara in her compound at the Thapathali Durbar complex and her initial years were spent in prayers and charity. The Nepalese public even gave her an affectionate nickname, Chanda Kunwar.

The story just gets more interesting here, of what this frail middle-age woman hoped to do after she had lost everything. From Nepal she wrote a long letter to the British Governor General, taunting him for not being able to imprison her for long. While in Nepal, she kept alive her attempts to somehow foment a rebellion in Punjab. During the Indian Mutiny of 1857, she wrote to the Maharaja of Kashmir to overthrow the British hegemony in Kashmir and move towards Gorakhpur, where the Nepalese army would join hands with him. She also told him about Nana’s and Tantya Tope’s presence in Nepal and exhorted him to fight in alliance with them. The letter was intercepted by the British and never reached Kashmir. But the British did not let her live in peace in Nepal, she was still a threat. She was under high surveillance of British spies and the Nepalese kingdom slowly felt the pressure of hosting her. Moreover, her no-nonsense and overpowering visage and her sense of pride was too aggravating for Jung Bahadur Thapa. Her activities were gradually curtailed, to the extent that she was again virtually under house arrest. The Nepalese were looking for a way to let go of her. She would however continue to remain in Nepal for 11 long years, all the time yearning for her beloved son, who had been snatched away from her. Till the day when she received a letter calling her to Calcutta. Her ten year old son, Dileep Singh, had meanwhile been taken to England and is said to have been a favorite of Queen Victoria and she considered him a royal member of her family. He was adopted to the wardship of the royal doctor and was given a seperate estate. He forgot all about his illustrious legacy and converted to Christianity, living his life as a British Aristocrat.

The contrast in treatment to all other royals of India is too evident to ignore. These two characters of history were too important and dangerous for the British to be pensioned off like all other royals of India. Yet, too precious to destroy. Killing them might have roused a revolt in the Sikh regiment which by now was the bedrock of British power in India. Maharaja Ranjeet’s Singh’s surrendered armymen had been recruited in the British Army as the famed Sikh Regiment (The Sikh Regiment still bears Ranjeet Singh’s insignia in conjunction with the Indian army insignia. This Sikh regiment in 1850s was the spearhead of British force, a counter-balance to the ‘Bengal Army’ which the Sikhs hated as a legacy of the Anglo-Sikh wars; an emotion that the British used to crush the 1857 Mutiny.) Dileep Singh tried and petitioned the British several times for news of his mother with a request to meet her. He was not allowed to meet her. So, on the pretext of a Tiger Hunt in India, he planned a visit to India. In 1860 he wrote to the British Resident in Kathmandu, enclosing his letter in one from his guardian Dr. Sir John Login so that it would not be intercepted or dismissed as a forgery. The Resident reported that the Rani had ‘much changed, was blind and had lost much of the energy which formerly characterised her.’ The British had decided that she was no longer a threat and allowed her to travel to Calcutta to meet her long lost son. It was then that she got a letter that called her to Calcutta, to meet her son. On 16 January 1861, Jinda met Dileep Singh at Spence’s Hotel, in Calcutta. It was a momentous day, it is said. Sikh Regiments was returning home via Calcutta at the end of the Chinese war. The presence of Sikh royalty in the city gave rise to demonstrations of joy and loyalty. The hotel was surrounded by thousands of armed Sikhs all eager for a view of their erstwhile queen and king. The atmosphere was of expectancy, and the prince was surprised at the love that he still enjoyed amongst his army. The British Viceroy, Lord Canning, got jittery and decided at the spot to remove both son and mother from India, dispatched to England by the next boat. And so, the erstwhile Maharani of Punjab set sail for the land of her conquerers. Her story does not end here. She was now with her son, a Christian in religion and a British Aristocrat in bearing. He had little idea of his past glory and was a faithful servant of the British empire. Landing up in Britain, Jinda was housed initially in a seperate housing but gradually moved in with her son, sick and frail, almost blind, with little of her former glory. Dileep Singh’s foster mother came to meet the erstwhile Maharani. It is reported about the meeting “compassion was aroused when she met a tired half-blind woman, her health broken and her beauty vanished. Yet the moment she grew interested and excited in a subject, unexpected gleams and glimpses through the haze of indifference and the torpor of advancing age revealed the shrewd and plotting brain of her” The British had confiscated all her jewels, worth a fortune. They returned some of these jewels to her. And during her visits to his son’s friends and foster family, she never failed to exhibit them. A portrait was commissioned of her in all her finery, and the poster is a testament to her determined poise.

She knew she was sick and was losing health fast. And she had a dream, of seeing Dileep Singh re-gain his power. She told him tales of his lost glory, of his magnificent father, and the indomitable spirit of the Sikhs, the Khalsa Raj of Lahore, the Raj that had stood independent for 60 long years when all around it everything other Indian kingdom had fallen to the British, the Raj that the British dare not attack even three decades after they had defeated the Marathas, half a century after they had killed Tipu Sultan and ages since the famed Rajputs had meekly surrendered in lieu of pensions, the Raj that had won Afghanistan, Bulochistan, Kashmir and had even had the gumption to attack the Chinese in Leh as far as Tibet and the passes around Mount Kailasa and Lake Mansarovar; the Raj that the British had defeated through treachery and back-stabbing. She brought him back to his faith as he started re-embracing Sikhism.

On 1 August 1863, shortly after 6:15 in the evening, the frail and partially-blind queen who had spent much of her life raging against the British Empire, died in her bed on the top floor of a Kensington townhouse. Cremation by Hindu/Sikh rites was then banned in Britain, so Dileep Singh requested the British to allow him to take her body for cremation to India. In Bombay state, on the banks of the Godavari she was laid to ashes, far away from Lahore; and a memorial Samadhi erected in her memory, till 1920s when her daughter-in-law took her memorial stones to Lahore and placed them in Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Samadhi. A headstone in Britain where she was buried for about an year awaiting her departure to India, has recently been unearthed in Kensal Green during renovations at the ‘Dissenter’s Church’. Her legacy lived a bit longer than her. Her son, reminded of his legacy gradually shook off his British up-bringing. He rebelled and wrote to the Russian Csar and tried to meet him to seek his help in his fight against the British. The Csar was however not convinced, being a relative of the British Tudors and Dileep’s attempts to persuade the Csar to invade India backfired spectacularly because British spies had followed his every move. Dileep Singh tried a few more tricks (that is a long story for another day), but the British were too powerful for him. Queen Victoria is however said to have a strong motherly relationship with him and saw him as a fellow royal. Even after he rebelled against the British Empire, she gave him a royal pardon but stripped him of some of his earnings. A number of historians now believe it was Jinda’s brief reunion with her son in the country she despised that rekindled Dileep’s desire to take back his kingdom. “In a way she had the last laugh,” says Harbinder Singh, director of the Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail. “When you look at the life of Duleep Singh the moment where he began to turn his back on Britain and rebel was immediately after meeting his mother. The British assumed that this frail looking woman, who was nearly blind and had lost her looks, was no longer a force to be reckoned with. But she reminded her son of who he was and where his kingdom really lay.” Dileep Singh died a pauper, in a decrepit hotel in Paris. None of Dileep’s children gave birth to an heir and his lineage died out within a generation. The Maharani died, the prince died, the lineage died, the legacy died; and with it died the story of this indomitable lady; the story of the Last Maharani of India, the last woman to stand eye to eye to the British. The story disappeared from the history books of India, never to be heard again. |

---------------------------------

Related Articles:

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/10-sikh-women-you-should-know-and-why-you-should-know-them

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/master-military-might

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/painting-maharaja-ranjit-singh-be-auctioned-march-18-new-york

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/photographic-bio-maharajah-duleep-singh-book-review

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/imperial-story-conspiracy-love-and-gurus-prophecy

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/princess-sophia-duleep-singh-biography

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/who-really-owns-koh-i-noor-diamond-part-i-op-ed

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/veil-duleep-singhs-restored-grave-near-london-tomorrow

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/should-koh-i-noor-be-returned-india

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/singh-twins-how-we-freed-last-maharaja-shackles-empire

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/10-badass-sikh-women-history

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/sikhs-britain-book-review

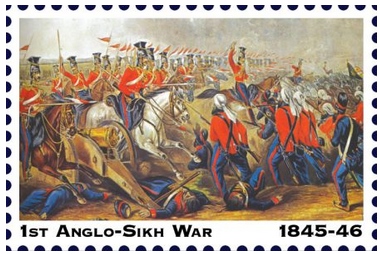

The British had not dared to attack Khalsa nation during Ranjit Singh’s rule. However, as soon as he died they started taking advantage of the instability created by his death. Jinda mobilized a vast army and waged two wars, the first and second Anglo-Sikh wars between 1846 and 1849. However, both wars were unsuccessful, and eventually led to the annexation of the Khalsa Raj to the British Raj in 1849.

The British had not dared to attack Khalsa nation during Ranjit Singh’s rule. However, as soon as he died they started taking advantage of the instability created by his death. Jinda mobilized a vast army and waged two wars, the first and second Anglo-Sikh wars between 1846 and 1849. However, both wars were unsuccessful, and eventually led to the annexation of the Khalsa Raj to the British Raj in 1849.