A life well lived is a life lived in devotion to God and service to God’s creation. People who lead such lives provide valuable inspiration for those who seek to live meaningfully. Some of us may be blessed with the good fortune of personally meeting such people and being able to learn from them by being in their presence. But even if we don’t get to personally meet such people we can still be inspired by their example—through reading accounts about them.

Published accounts of the lives of men and women of God are a great way to gain inspiration and ideas for leading a more meaningful life. Irrespective of what our own beliefs may be, we can benefit immensely by reading about the lives of men and women of God from various religious and spiritual traditions, for goodness and wisdom know no religious or ideological barriers.

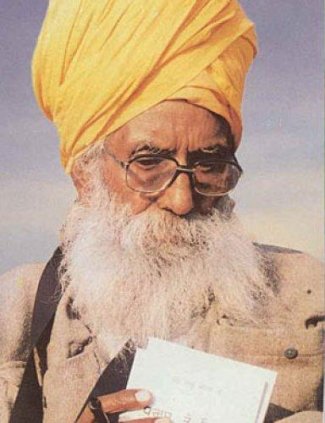

Recently, while at a bookshop, I picked up a copy of a book about one such inspiring person. His Sacred Burden: The Life of Bhagat Puran Singh, by Reema Anand which tells the story of a Sikh man from Punjab who did some wonderful things with his life. In his introduction to the book, the late Khushwant Singh, well-known writer, remarks, “In living memory, Punjab has not produced as great a man as Bhagat Puran Singh.”

Bhagat Puran Singh, or Bhagatji, was born in 1904, in a village in Punjab and was given the name Ramji Das. His mother, Mehtab Kaur, was a pious woman. Anand’s portrayal of how Mehtab Kaur tended to her child, inculcating virtues in him from a young age, underlines the important role that mothers often have in the spiritual formation of children who go on to lead truly meaningful lives. “Unconsciously or consciously,” Anand explains, “she was grooming sensibilities which would render in him the remarkable qualities he revealed very early in life and which he sustained till his death.”

From his mother, Ramji Das learnt invaluable lessons in love and compassion. She taught him, for instance, to look down while walking so that he wouldn’t step on little insects. Mother and son would spend the afternoons tending to the cattle, and Bhagatji was later to reflect: “As I saw them drinking water, a great surge of happiness would course through my being. An unfamiliar coolness would descend on me—as if it was my thirst which was being quenched’.

Mehtab Kaur was fond of trees, and Ramji Das would help her plant saplings. He would watch his mother pick up sharp nails, thorns, fruit peels and big stones that lay about. Following suit, he would ask her why she did so. She would explain that thorns and nails might pierce someone’s feet, while the stones might obstruct people’s path. Silently, Ramji Das absorbed this sort of sensitive reasoning and applied it to his own life.

The caring attitude towards humans and animals that Ramji Das’s mother cultivated in him became more pronounced as time went by. (Ramji Das’ once wealthy family suffered great economic loss, compelling Mehtab Kaur to work as a domestic help in someone else’s home in a distant place in order to earn, but even then, she never let up on her loving concern for her child, saving her meagre earnings to enable him to continue with his education.) Of his relationship with his mother, Bhagatji later remarked, “The best part of our interaction was that she never imparted her advice to me as a sermon; it always came with a reasoning I could digest”.

A major transformation occurred in Ramji Das’s life around the time when he had appeared for his matriculation exam, when he felt drawn to the Sikh faith on meeting some compassionate Sikhs and visiting a Gurdwara. He soon shifted to Lahore, where he started going to the Gurdwara Dehra Sahib daily. He now came to be known as Puran Singh.

A new chapter in Puran Singh’s life began as he began doing sewa or voluntary service in the Gurdwara. He started working in the hall where the langar (the community kitchen in every Gurdwara that is open to one and all) was held. His duties included kneading the flour, lighting the fire, cleaning the hall and washing utensils, for none of which he accepted any monetary reward. Then, after his duty hours were over, he would rush to a library, where he would devour books on a wide range of issues. Even though he failed to pass the matriculation examinations after repeatedly trying, he loved reading. (Though he never finished his basic schooling, Bhagatji was to later become a writer and a self-publisher. A Wikipedia entry on Bhagatji says “...he was not interested in studying his course books, which he felt were filled with hypothetical and theoretical knowledge with absolutely no connection or applications to everyday life. He, however, would spend hours browsing books in the Dyal Singh Library, trying to gain as much knowledge as he could.”)

Anand comments: “Puran Singh’s hunger for knowledge was not restricted to just school and academics. It was multidimensional... There was no discipline he left untouched. Whether sociological, psychological, physiological, emotional, religious or any other, he had analysed all sorts of problems with the passing years and offered solutions to those who sought them.”

Reflecting the important role that reading had on shaping his life’s vocation, Bhagatji later wrote, “Once I chanced to read about Florence Nightingale. Since them she became my inspiration for serving humanity... I was even more drawn to this benevolent lady’s personality when I learnt that to be able to serve the people better, she had remained unmarried.”

Anand relates that Bhagatji continued to read, write and print articles till the end of his life and became one of the most widely read personalities in the Sikh circles. People would often ask him, “Don’t you get tired of reading? What do you gain from it?” And he would reply, “Everything that pertains to the living creatures is of interest to me.”

In 1934, two Sikh landlords visited Gurdwara Dehra Sahib. They brought with them a three-year-old boy who was partially deaf and dumb as well as mentally handicapped and left him at the Gurdwara’s entrance. The child fell sick with dysentery. Reminiscing about those days, Bhagatji wrote: “His condition was pitiable. He was left on a rubbish heap with sharp stones jutting out of it. He kept defecating and crawled a little away from the faecal matter each time. No one came to clean him. I also kept watching...watching the helpless boy and my own reactions. By evening, after defecating countless number of times, the poor boy was listless and feeling very weak. My eyes became teary and a deep sadness filled my soul. An anxiety coursed through my being and I felt restless energy in me transforming itself into a decision.”

The next day, Bhagatji bathed the child, dressed him in clean clothes and carried him on his back to the Gurdwara. In the main prayer hall, he cried as he prayed, “Oh, dear Guru! As your true disciple, a Gursikh, I adopt this boy as my own.” He informed a doctor about the child’s condition, and with proper medication and affectionate care, the child’s health began improving. Bhagatji named the boy Piara Singh, ‘the loved one’. Piara gave Bhagatji a reason to live, and for 13 years, Bhagatji roamed the streets of Lahore with Piara on his back. “Piara had become Bhagatji’s lifeline,” Anand says. “The joy he experienced in looking after him was divine.” His joy “lay entirely in looking after Piara.” Bhagatji wrote, “The kind of love I received from my mother until her death, I tried giving the same to Piara”.

In the middle of August 1947, when Lahore faced the frenzy of Partition-related violence, Bhagatji and Piara, along with many others, were forced to relocate. They shifted to Amritsar, where huge numbers of refugees had taken shelter. Bhagatji had not much money nor a roof above his head, and he had Piara to look after. But this man of God did not lose hope or a sense of mission. He went to the huge refugee camp at the Khalsa College, where he began looking after handicapped people who were in a terrible state. This he did with Piara on his back (there was no one under whose care he could leave him, and Piara apparently wouldn't stay without him for even 5 minutes.) Many of these handicapped people around the college grounds lay in their own excreta, covered in soiled and stinking clothes. Bhagatji’s main task was to keep them clean and arrange for food for them.

The Khalsa College refugee camp in Amritsar was full of misery. Bhagatji lived on roadsides for almost a year and a half, “like a beggar,” Anand writes, asking for food for his patients. He had a bell around his neck—he would ring it and go from house to house and obtain alms.

Later, Bhagatji set up his own camp, near the Amritsar railway station, for physically challenged destitute people. He wanted to set up a centre for handicapped people, where he would tell his sewadars, “there will be no physical or religious discrimination against anyone. All will be welcome; whoever shall need me, I will be there for him.”

Bhagatji’s main task till 1951 was washing the stinking clothes, soiled with faeces and pus, of the destitute and handicapped people he was tending to. He would also clean up their stools and urine himself. “I always kept this particular job for myself, not exposing my sewadars to it, for it was very repulsive and not every man’s cup of tea” he said. He’d make a big bundle of these clothes and go to the railway station and wash it there. “If I had started thinking about these jobs from the angle of repulsion, it wouldn’t have been sewa any more... Once I started looking upon them as my own children—just as I considered Piara—it was only love I felt”, he explained.

Khushwant Singh notes that at the Pingalwara, the home that Bhagatji set up for the people he tended to, “No discrimination was ever made on grounds of religion or caste: its inmates included Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims”. Anand observes that emotionally and physically ostracized humans were taken care of in the Pingalwara irrespective of their religion, caste, class or gender. She explains that Bhagatji took to begging on the streets and outside places of worship, asking people to help the needy. He had no grants or institutions to back him, she says, but his faith in God, as well as in his fellow humans, “was unshakable.”

When in 1950 Bhagatji shifted to an abandoned cinema hall, he had 90 invalids in his care. The complex gradually expanded, with new rooms being built and people making financial contributions for the noble cause. The Pingalwara became a refuge not only for people in distress but also stray or sick animals.

Today, many years after Bhagatji’s death in 1992, it continues as a home that tends to the castaways of society: the sick, disabled and abandoned, forlorn people.

Towards the end of his life, Bhagatji was very concerned with environmental issues. He would collect articles on the subject and get them printed and distributed. In the later years of his life, when financial contributions were available, and he could easily have afforded vans, he continued to use rickshaws to ferry his patients to and from hospitals and a tonga for himself. His constant advice to people, like a true environmentalist, was to walk at least eight kilometres a day!

When Bhagatji died in 1992, he wanted a broom to be kept beside his bier—so that people would know that a sewak or servant of the Guru had passed away. His wish was fulfilled.

Bhagatji’s eventful life beautifully highlights the basic ingredients of a life lived truly meaningfully, one spent in service of God and God’s creatures. It provides us valuable guidance for how we can spend our own life in a more meaningful way.

Some Salient Learning Lessons from Bhagatji’s Life:

- As Mehtab Kaur’s relationship with her son shows, mothers have a key role to play in the spiritual formation of their children. They need to pay attention to passing the right values to their children through their own personal example and sacrificial love.

- Experiential knowledge is important, not mere academic knowledge. Bhagatji didn’t complete his basic schooling, but yet grew into a wise and compassionate man.

- A meaningful life is one based on devotion to God.

- Devotion to God must be expressed through service to God’s creatures, especially the needy.

- Love for God’s creatures must be universal, transcending boundaries of religion, creed and caste. As Bhagatji’s example shows, it should embrace all creatures of God, including animals and plants.

You can learn more about Bhagatji and Pingalwara here