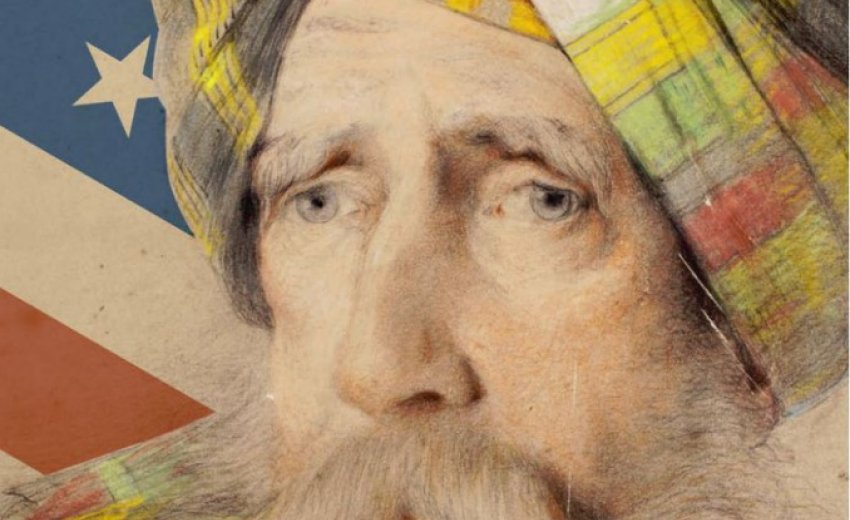

The Turbaned Human Kaleidoscope - Book Review: The Tartan Turban: In Search of Alexander Gardner

Look for a minute into the eyes of the man pictured on the left. A steely, almost worried look stares out from under furrowed brows. John Keay's new history on adventurer Alexander Gardner, published by Kashi House, animates the story behind that distant stare.

Gardner was an American adventurer. His story reads like a 19th century James Bond novel. Sometimes the details of his story are murky, but during a long life on the move, Gardner would come to serve the greatest empire of its time: the Sikh Empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Now, shift your focus to his face. Already, symbols of Alexander Gardner's past make themselves known. Long, salt and pepper whiskers jut out and curl upwards in the Rajput fashion. Perhaps his style was influenced by his patron, the Dogri Rajput Maharaja of the then- newly established Princely state of Kashmir. The maharaja's late brother, one of the three infamous Dogras, was Gardner's former retainer and one of many in a line of scheming viziers, ambitious rulers, and political agents that Gardner called boss.

The checkered tartan of his turban and matching suit speak more to his penchant for personal flair than the Scots regiment to which they belonged. The turban itself says more. It speaks to Gardner's ability to adapt and blend into the many disparate cultures through which he moved. From the barrens of Central Asia to the lush plains of the Punjab, Gardner's outward appearance and purported ancestry shifted to match the culture that surrounded him. His official conversion to Islam while traversing the brutal Islamist Khanates of Central Asia in the early 19th century is possibly the most potent example of his ability to adapt for survival. In Turkic Central Asia, being labeled an infidel was sometimes as good as a death sentence.

An egret plume is affixed to the top of his turban, swept back like a Musketeer, revealing his courtly status. Commanders who risked life and limb for their retainers were rewarded with such status symbols for their loyalty and bravery. And brave Gardner was. Despite reports that he maintained a sprightly gait in his later years, the Colonel's body was riddled with bullet wounds and the scars of sword slashes. A testament to his resilience, Gardner once had his throat cut by an enemy sword and survived. Gardner was then forced to close the cavity with forceps whenever he ate for the rest of his life.

His Sword could be booty held over from his time serving the Sikh empire in Punjab under the mythic Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Perhaps it was wielded while carrying out any number of gruesome deeds for his many masters in the Sikh court. Whether murdering rival courtiers alongside the Dogra brothers or ambushing Turkestani bandits, Gardner was a killer. He does not come across more or less bloodthirsty than his contemporaries, but the needle of his moral compass was likely a gold-filigreed scimitar. Wealth and survival were his imperatives and sometimes the securing of one led to the jeopardy of the other.

As much as we search Gardner's haunted eyes to understand the man that many called a charlatan, Keay vividly paints the world and characters that they looked upon. Tolkien-esque descriptions of the bleak world of the Pamir Mountains, contrasted by vivid accounts of the swirl of colors, cultures and indulgences of 19th century Lahore, originate from the Colonel's piecemeal memoirs and prodigious contemporary sources. As the kaleidoscope of Gardner's story turns, the many little pieces that make up the record of this man's life and times begin to fall in place. The image that the reader is eventually faced with is equal parts beautiful and horrific - perhaps a touch more of the latter. Any readers familiar with the bloodshed surrounding the succession of the Peacock Throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the eventual implosion of the Sikh empire will understand why.

The questions of veracity surrounding Gardner's purported adventures are understandable. Like some kind of 19th century space probe thrust through a tear in the dimensional fabric to explore new worlds, Gardner moved through a sizable chunk of the planet that no one in the "civilized" world had ever seen and lived to report. How do you verify the story of a man who tells you he marched through lands that were unlabeled on maps? Keay meticulously pulls apart Gardner's timeline and uses existing and newly discovered sources to set the record straight.

Gardner's time spent among the Sikhs will likely draw particular interest, especially among the pre-existing Kashi House fans. Mercifully, Keay gives us a glimpse into what was one of 19th century Asia's superpowers in all of its glory. In its day, the Lahore court was a legitimate military and economic rival to the might of the British Empire. Along with that power came incredible wealth that lured travelers, merchants, and mercenaries from every corner of the world. Gardner's arrival feels like a sigh of relief after his harrowing journeys through Central Asia. He impresses the old emperor with his self-taught artillery skills and secures a station commanding a small battalion.

The respite is brief. Maharaja Ranjit Singh dies not long after Gardner's arrival and the empire begins its slow march into the sea. After the third post - Ranjit Singh regicide, it would be excusable for the reader to shout at the text in frustration. If only one of the many vain, power hungry, murderous agents could hear our pleas to, well, stop murdering each other. Maybe if the Khalsa Army didn't murder Jind Kaur's crazy brother or Jind's crazy brother didn't murder Peshora Singh, favored by the Khalsa, or if Peshora Singh didn't illegitimately declare himself Maharaja and defy the Lahore court, they could have avoided the Anglo-Sikh wars and remained trading partners with the British. Alas, the story does not unfold that way.

No one is innocent nor explicitly guilty in the demise of the Sikh empire. There are too many players. Through the stark lens of history, illuminated by Keay's exemplary research, the oft deified Sikhs of yore look like just another group of human beings wrapped up in the machinations of empire. Internal strife caused by greed created external vulnerability and the rival British eventually seized their opportunity to consolidate their hold on the Sub-Continent. Somewhere in the middle of this whirlwind of blood and gold, Gardner played his part and, as he had always done, survived.

Keay's handling of this vast story demonstrates his skill and the quality of his literary aesthetic. At no point did I feel like I was reading dry history. Each chapter was a sudden turn in the kaleidoscope, shifting to reveal a new facet of Gardner. Known to embellish and exaggerate, Gardner's story is not a simple one to get straight. Keay comes as close as we likely ever will and the process is a joy to follow.

Detail of miniature depicting the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh