View more images - Photos by Zoe Strauss

Joseph Artmont Sr. is among the last standard-bearers of Millbourne’s old guard. Sixty-nine years old, the volunteer fire chief moved here as a child from West Philadelphia, where white middle-class families like his were moving out and lower-income blacks were moving in. He’s been here long enough to observe sweeping changes in tiny Millbourne — a less-than-one-tenth-square-mile Delaware County borough wedged between West Philly’s Cobbs Creek Park and Upper Darby — and long enough to know he’s unhappy with them.

Two decades of large-scale immigration are transforming the region. Philadelphia, after losing a quarter of its population in a post-industrial free fall, in 2010 grew for the first time in 50 years thanks to new arrivals from Latin America, Africa, Europe and especially Asia. Across greater Philadelphia, there are 59,987 Indian immigrants, more than any other national group. But the immigrant population has ballooned even faster in the suburbs — and nowhere more so than Millbourne. Today, 56 percent of Millbourne’s 1,159 residents are Asian, and fully 30 percent are Indian.

Two decades of large-scale immigration are transforming the region. Philadelphia, after losing a quarter of its population in a post-industrial free fall, in 2010 grew for the first time in 50 years thanks to new arrivals from Latin America, Africa, Europe and especially Asia. Across greater Philadelphia, there are 59,987 Indian immigrants, more than any other national group. But the immigrant population has ballooned even faster in the suburbs — and nowhere more so than Millbourne. Today, 56 percent of Millbourne’s 1,159 residents are Asian, and fully 30 percent are Indian.

“Sometimes, very big difficulties with that,” says Artmont of his borough’s newfound diversity. “People don’t talk your language. It’s hard communicating.”

Alongside the old bowling alley and the auto-parts store, Indian-owned businesses now line the side of Market Street that belongs to the microborough (where infamously scrupulous meter maids are on seemingly constant patrol). There’s also a Korean restaurant, but no prepared Indian food for curious visitors, unless someone invites you to dinner. Indians, I was told twice, don’t much see the point in eating out.

The Sikh temple is on the borough’s western border, and a neon-orange cloth reading “Philadelphia Sikh Society” is available if you, like me, arrive without your own head covering.

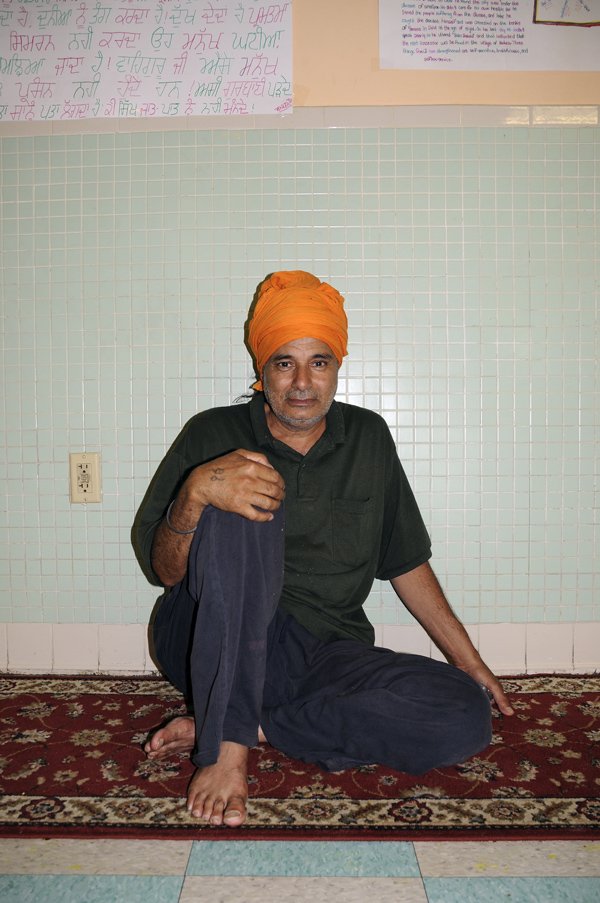

“All that food?” says Harbhejan Singh, surveying the rows of people sitting on long mats, a crowd gathered for Sunday’s communal meal. “I’m paying for it.”

Singh — and, as a statement of equality, most Sikh men have the last name Singh, meaning lion (women take the name Kaur, which translates to princess) — pays for the daily meal, or langar, once each year. Men who are not lounging mop the floor and scrub pots and pans. Sikh temples, or gurdwaras, are famously spotless.

As to how a hub of Sikh and South Asian culture landed in this dense pocket of small-town development, cab driver Iqbal Singh explains what many others will tell me: He came to Philadelphia because he already had family here. And anyhow, New York is too expensive.

Paramjit Singh, a soft-spoken priest who wears an equanimous smile, a crisp white tunic and a long black beard below a neatly coiled turban, guides me to the adjacent room. This Sunday is the Sikh summer-camp finale, and children march to a podium to deliver historical lessons in front of a few hundred community members. They alternate between Punjabi and English, standing before a PowerPoint backdrop.

A teenage girl explains that Sikhs frown on divorce and that, though Sikh men are beginning to marry non-Sikh women, they should not. Then Paramjit takes the stage behind the tabla while two young girls play harmoniums. “The guru, the perfect, true guru, has blessed me with peace and tranquility,” the chorus sings in Punjabi.

An elderly man waves a wand with a yellow frond before an altar swaddled in bright-pink cloth. Congregants approach and place dollar bills on a growing pile.

Ann Alto, 48, grew up Catholic in Yeadon but has been a Sikh for one year. “It’s focused on God and prayer and common meals,” she says. “But I still haven’t abandoned Catholicism. Trying this out. Catholicism is beautiful, too.”

The transformation here isn’t just cultural. In recent years, Millbourne has joined the growing number of municipalities that — thanks to new arrivals: immigrants from overseas and African-Americans from Philadelphia — are challenging the Delaware County Republican Party machine. Over the last few elections, Artmont Sr. and his white Republican allies, including son Joseph Artmont Jr., were ousted from the five-member Borough Council, which is now controlled by two Bangladeshis, one Punjabi Sikh, one Keralite Indian and one white Democrat named Jeanette MacNeille.

“Most of the immigrants are brought up being Democrats,” Artmont Sr. laments. “That’s basically what the problem is. Now, do they understand what really, really goes on, and what they’re voting for? They can’t talk and understand what they’re reading when they get here. But they tell them, ‘Here’s what to vote,’ and that’s what they do.”

Mayor Tom Kramer, the last Republican standing, is a liberal who ran on the immigrant-heavy Democratic ticket. First, Kramer defeated Kurian Mathai — a local landlord and tax delinquent who owes more than $130,000 in property taxes — in the Democratic primary. By September 2009, just two months before the general election, the atmosphere was tense. Minutes from a Borough Council meeting record Republican incumbent Mayor William Donovan Jr. accusing Council candidate Khiet Luong, who had brought a digital recorder to the meetings, of using “some sort of listening device, which he should show Council.”

The diverse Democratic slate, however, gradually took over the board. These days, says Kramer — who wears sandals, shorts and a shirt unbuttoned to mid-chest as he leads me on a tour down the borough’s few streets during a heat wave — the issue is really immigrants leaving.

“When people buy into the American dream of a two-car garage and a swimming pool,” they see Millbourne “as just a way station before they move to Broomall.”

Koreans moved out over the past decades, just as Greeks and Italians had before.

Councilman Alauddin Patwary, a Bangladeshi who has lived in Millbourne for 23 years and owns a shop in Kensington, says he plans to stay. He is involved, he says, because “sometimes people are complaining, they don’t like this, ‘Blah blah blah.’ So I set my mind: I am interested in running for Council.”

The borough’s most pressing issue is a long-standing one: How to fill the vast empty lot abutting the borough’s Market-Frankford El stop. It’s a blight on what Kramer estimates is one-third of Millbourne’s land, where Sears shut down in 1988 to relocate to Upper Darby (where it ended up closing this year). Kramer wants someone to build a multi-ethnic Little India food mart there.

The borough’s most pressing issue is a long-standing one: How to fill the vast empty lot abutting the borough’s Market-Frankford El stop. It’s a blight on what Kramer estimates is one-third of Millbourne’s land, where Sears shut down in 1988 to relocate to Upper Darby (where it ended up closing this year). Kramer wants someone to build a multi-ethnic Little India food mart there.

Delaware County Democrats predict that Upper Darby, Millbourne’s 82,795-person next-door neighbor, will also fall to the demographic tide.

Councilwoman Marah Manners, a Dominican immigrant, was in 2011 elected as Upper Darby’s only Democrat. Her district is incomparably heterogenous: Vietnamese, Korean, Jamaican, Indian, Bangladeshi, Irish, Greek, Mexican, South American and African.

Mayor Thomas Micozzie says Upper Darby Republicans will win immigrant votes as long as they can deliver voters a high quality of life. “I respect their religion, they respect mine. … I’ve been at the Sikh temple. I eat oxtail with Haitians. I think they’ve learned enough in the voter process here that, if you take care of the people that take care of you, then you have a good culture.”

Sheikh Siddique, a Bangladeshi who owns an Exxon station in Lansdowne, is a leader in the Upper Darby Democratic Party and narrowly lost the primary to Manners.

“We are working shoulder-to-shoulder with the other Democrats, the whites and African-Americans,” he tells me while selling lottery tickets and gas from his bulletproof dais. “We’re working together to get control of Upper Darby Township. We’re talking about another five years. We’re very close.”

Back across the border in Millbourne, Artmont is, again, not happy about all of this. But he does seem somewhat resigned. He is even a little enthusiastic about two Indian-American teenage girls who now volunteer at the Fire Department. “They came in, and I was very surprised to see them. … They’re doing a very good job.”

But Artmont keeps the world just as he likes it tucked away in his basement, where a complex set of intersecting train tracks pass through an expansive diorama of small-town Americana.

“Something different,” he explains. “You know what I mean?”

This project was made possible by a fellowship from the French-American Foundation-United States. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views of the French-American Foundation or its directors, employees or representatives.