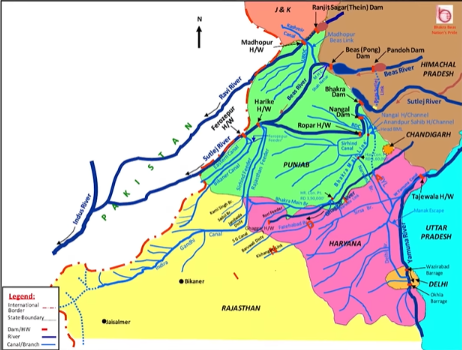

Punjab’s river water crisis started appearing just two years after the country’s independence when, in 1949, the Punjab government sent a proposal to the Central government to build the Harike Headworks. The Central government’s bad intentions became clear when it put the condition that this proposal would be implemented only if the Punjab government agreed that from these headworks, 18,500 cusecs of water would also be given to Rajasthan. Call it Punjab government’s carelessness, weakness, or helplessness, but Punjab approved this fully unjustified proposal of the Centre. Under these adverse conditions, the Harike Headworks were built and completed in 1952.

The surprising fact is that Rajasthan, for whom this water arrangement was made, had never before asked for or demanded water from Punjab’s rivers from the Central government. Actually, Rajasthan knew that being a non-riparian state, it had no right whatsoever over the waters of Punjab’s rivers. It also knew that if it demanded water from Punjab in this situation, it would have to pay for it, just like Bikaner used to pay for Punjab’s river water through Gang canal, which it could not afford. It also knew that Jaisalmer’s area was much higher than Harike Headworks and lifting water from a low area to a high ground is a very difficult task.

Due to its own incompetence, Punjab did not assert its claim over all of its rivers’ water. Hence, the World Bank team was told that up to 15.85 Million Acre Feet (MAF) of additional water from Sutlej, Beas, and Ravi rIvers could be used. The Centre then conspired to allot 8.00 MAF water to Rajasthan. At that time, Punjab should have properly planned for the future of its agriculture. Accordingly, it should have demanded 15.85 MAF additional water instead of only 7.25 MAF. It was really an egregious blunder by the government of Punjab. Also, the Union government went out of its way to help Rajasthan. While unduly favouring Rajasthan, it did not care at all about some sandy and dry areas of Punjab which were urgently in need of river waters. If the Centre was really unpartial, it could have reviewed the scheme and made it somewhat more favourable for Punjab.

Anyway, from Harike Headworks to Jaisalmer in Rajasthan, a 1680 Kilometer long and about one acre wide canal, one of the world’s longest and widest canals, known as the Indira Gandhi Canal, started being built in 1956 entirely with central funds. It was completed in 1965. From 1965 till now, a huge share of Punjab’s river water is being taken away to Rajasthan through this canal. Moreover, the canal’s 167-kilometer length within Punjab ruined 9,000 acres of the state’s fertile land, and the effects of waterlogging spread far and wide. Almost all canals flow from high to low ground, but this is probably one of the very few canals throughout the world that flows from a low area to a high ground. It may be mentioned here that Jaisalmer of Rajasthan is about 100 feet higher than Punjab’s Harike Headworks. To get water to this high area, powerful motors were installed at two places to lift water 60 feet each at both places.

Before building the Indira Gandhi Canal, the Indian government had taken advice from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation regarding this canal. After four years of deep study, in 1954, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had advised the Centre not to build this canal to irrigate the sands of Rajasthan’s desert. The American Bureau had further stated that with this water, it would be better to irrigate the areas near Punjab’s rivers. But the Centre ignored this sane advice and decided to go ahead with constructing the canal. Punjab lost its land and water, and that too for a non-riparian state (Rajasthan). It is crystal clear that, according to the world’s water-sharing principles, Rajasthan had no right or claim over Punjab’s rivers. Surprisingly, the Union government ensured that Rajasthan would get all this water and that too without paying for it. It may be mentioned here that, before India’s independence, the Bikaner State (part of modern Rajasthan) used to pay ‘seigniorage charge’ (royalty) to the Punjab government for using water from Punjab’s Sutlej river. Bikaner used to receive Punjab’s river water through the old Gang canal.

According to some rough calculations, if the price of water given by Punjab to Rajasthan is calculated, it would be about 11.75 lakh crore rupees (this estimate is based on the 2008 C.W.P.C. report; it was prepared in 2018). Now, in 2025, this amount will naturally increase very significantly. With such a whopping amount, the entire debt of Punjab and also of its farmers could be paid off, and even then, several lakh crores of rupees would be left, with which poverty and unemployment could be fully eradicated in Punjab.

If the Central government wanted, instead of making Punjab barren, it could have given water to Rajasthan from the Narmada or Sardar Sarovar Dam in Gujarat, but neither the Centre nor the Gujarat Government was prepared for it.

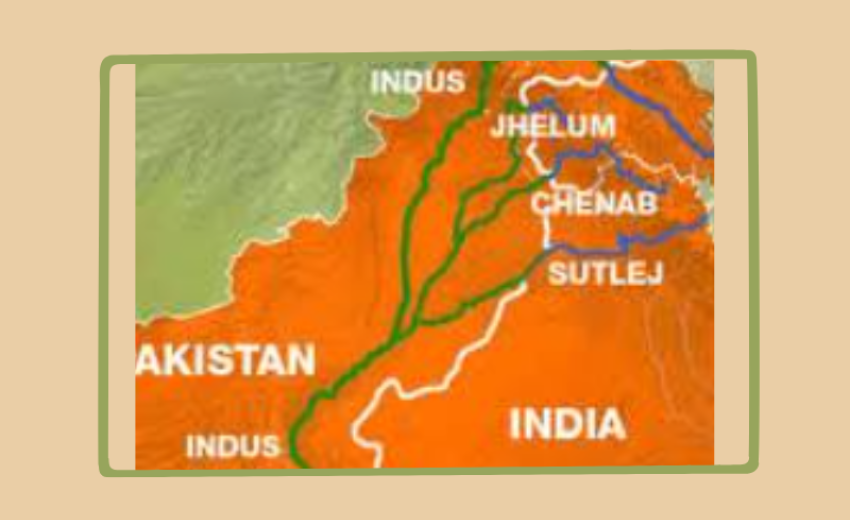

It would not be out of place to mention here that the Indus Waters Treaty, which was signed in 1960 between India and Pakistan, was very badly negotiated by India. While Pakistan was unduly favoured, India, particularly the Indian Punjab, suffered immensely by implementing the one-sided treaty. Once, when Nehru was asked about it, he had cooly said that he believed that India would have very cordial relations with Pakistan because of the treaty which unduly favoured that country. We all know that Nehru was repeatedly proved wrong by Pakistan.

Now, let’s turn to Haryana. After coming into existence in 1966, Haryana rightly believed that the political leaders of Punjab were very incompetent and simple-minded. If Punjab could give its river waters to Rajasthan for free without any proper reason, then why can’t they similarly serve Haryana also? Hence, Haryana claimed a right over Punjab’s rivers, stating that before the reorganization, it was a part of Punjab; so now it should get a share of the water from Punjab’s three rivers according to its area.

During the use of the Reorganization Act 1966, the Centre also added three clauses (78, 79, 80) that should not actually apply to inter-state rivers. Under these clauses, it was arranged that the leaders of Punjab and Haryana would sit together with the advice of the Central government and resolve the water issue within two years; otherwise, the right to resolve the issue would go to the Centre. As was rightly anticipated, no agreement could be reached between Haryana and Punjab, and, therefore, the Centre stepped in. In 1976, taking advantage of the Emergency in the country, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi forced her decision on Punjab allotting 3.5 MAF more water to Haryana from Punjab’s Ravi and Beas rivers. Haryana, striking while the iron was hot, said that to get this 3.5 MAF water into Haryana, a new canal should be built because the existing canal did not have enough capacity to carry this additional water. This planned canal came to be known as the Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal.

Ideally, as soon as Haryana became a separate state, all the small and big canals taking water from Punjab’s rivers to Haryana should have been immediately stopped, or Haryana should have been made to pay for the water. But Punjab’s political leaders did nothing like this. Haryana, despite being a non-riparian state, kept getting Punjab’s river water for free. As regards the SYL Canal project, under the stewardship of Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal, the parcels of land (which had earlier been acquired for the SYL Canal project) were returned to the original farmers and their descendants free of cost. Consequently, many farmers physically reclaimed and levelled their lands for cultivation. The Supreme Court later held that Punjab legislature could not unilaterally terminate water-sharing agreements or related court orders.

Unfortunately, the rules relating to the distribution of river waters between various states of India are applied differently in case of different provinces. In 1953, during the reorganization of Madras (Chennai) state, Andhra Pradesh was separated from it. Before the birth of the new state, three rivers—Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri—were flowing in Madras state. After the division, Andhra Pradesh got Godavari and Krishna rivers. Hence, Madras state became a non-riparian state for these two rivers. In spite of repeated requests by Madras state, Andhra Pradesh refused to give any water to that state from these two rivers. In fact, the water flowing in Godavari and Krishna rivers is even more than four times than that of Punjab’s rivers (Godavari = 100 MAF, Krishna = 60 MAF, Sutlej+Beas+Ravi = 34.3 MAF). After the division of Madras state, Andhra Pradesh never claimed any right over Kaveri river because it became a non-riparian state for that river. There are scores of such examples in India as well in other countries where, after division, non-riparian states, regions, or countries did not get water from other rivers. Servai’s Constitutional Law of India is already available on this subject, which is universally accepted. Unfortunately, however, exceptions have always been made in the case of Punjab, thus depriving this state of its own precious river waters.

After 1966, Haryana became Punjab’s neighbourly state. At that time, Punjab should have asked for water from Haryana’s Yamuna river (just as Haryana had demanded water from Punjab’s rivers). But Punjab’s incompetent leaders never forcibly laid their claim for this. Now, Punjab gets only 8.00 MAF from its own rivers. At the same time, Haryana is taking about 7.00 MAF from Punjab’s rivers, 5.60 MAF from the Yamuna, and 1.10 MAF from the Ghaggar. In total, compared to Punjab’s 8.00 MAF only, Haryana is using 14.50 MAF.

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Shiromani Akali Dal President Sant Harchand Singh Longowal signed an agreement on 24 July 1985, known as the Rajiv-Longowal Accord. Out of its 11 clauses, clauses 9.1, 9.2, and 9.3 pertain to the distribution of Punjab’s river waters. This accord clearly shows that Longowal miserably failed to safeguard Punjab’s interests (particularly the ones relating to the distribution of Punjab’s river waters).

All of the agreements made so far regarding Punjab’s river waters—whether the 1955 decision, or those of 1966, 1976, 1981, 1985, or 2002—are actually unconstitutional, and illegal. All of Punjab’s rivers flow through Punjab’s land, and according to Article 246 of the Indian Constitution, only the Punjab Legislative Assembly has the authority to make any decision regarding them. Yet, all these agreements have been made under Articles 245 and 262, which are applicable only in case of inter-state river disputes.

What is the meaning of the Rajiv-Longowal Accord? Rajiv Gandhi had no connection to the Punjab Legislative Assembly, nor did Harchand Singh Longowal. Rajiv Gandhi was the country’s Prime Minister, and Harchand Singh Longowal was the president of a regional political party, and an ordinary citizen. According to Article 246 of the Constitution, neither the Prime Minister nor the Akali Dal president has any authority to make decisions regarding Punjab’s river waters without the Assembly’s approval.

On 5 November 1985, Punjab’s Chief Minister Surjit Singh Barnala rejected Darbara Singh’s 1981 agreement in the Punjab Assembly, but did not say anything about rejecting the Rajiv-Longowal Accord of 24 July 1985, even though both agreements were illegal and unconstitutional.

The fact is that, from 1950 to 2025, the Akali, Congress, Akali/BJP, and AAP governments in Punjab, for their own narrow political interests, have repeatedly sacrificed Punjab’s vital interests and deceived its own people. For their vested interests, Punjab’s most political leaders sacrificed the real interests of Punjab (particularly the ones relating to Punjab’s river waters).

Between 1960 and 1970, several important events occurred, such as the inauguration of the Bhakra Nangal Dam in 1963, the opening of the Indira Gandhi Canal for Rajasthan in 1965, the loss of Haryana during Punjab’s reorganization in 1966, the transfer of some hilly areas of Punjab to Himachal Pradesh, and the first Green Revolution in 1965-66. All these events gave a new direction to Punjab’s economy, society, and future.

The Bhakra Nangal Dam, for which Punjab had been waiting for more than five decades, was handed over to Himachal Pradesh during Punjab’s reorganization in 1966, and its control was given to the Bhakra-Beas Management Board, leaving the helpless Punjab government to watch silently. Extremely huge volumes of water from Punjab’s rivers were handed over to Rajasthan, Delhi, Haryana and Chandigarh for free, and the Green Revolution was imposed on Punjab.

As is well known, water is of paramount significance for agriculture. Out of the surplus from Ravi and Beas rivers, Punjab was left with only enough water to irrigate about 25% of its land. It was crystal clear that if Punjab wanted to irrigate the remaining 75% of its land also, then it would have to rely on groundwater through tube wells. Thus began the era of tube wells in Punjab. The Green Revolution, water, and electricity became interconnected. The number of tube wells increased, and so did the need for electricity. For a while, the additional electricity from the Bhakra Dam and other sources met the need, but as the number of tube wells and the population grew, the demand for electricity rose so much that power cuts became routine. It would not be wrong to say that today, just to irrigate 75% of the land with groundwater, more than 16 lakh tube wells are running in Punjab, requiring about 1,150 crore units of electricity each year, costing around 5,800 crore rupees. This much electricity is produced by four large power plants. Over the years, during the last 50 years or so, Punjab has consumed more than 2,32,000 crore rupees worth of electricity just for irrigation. Each tube well costs at least 3 lakh rupees to install, and over the last 40 to 50 years, due to falling groundwater levels, farmers have had to dig new bore wells 3 to 4 times, with each farmer spending about 12 lakh rupees, and for 16 lakh tube wells, the total cost comes to about 1.2 lakh crore rupees. In other words, Punjab and its farmers have spent about 3,52,000 crore rupees just to irrigate 75% of the state’s irrigable land.

This does not include the costs of setting up and running power plants, salaries of employees, and the loss of valuable land submerged by these plants. All this expenditure could have been avoided if Punjab’s river water had remained within Punjab. There would have been no need for so many tube wells or power plants.

If, in recent times, Punjab’s governments had been sincere about Punjab’s rights, today Punjab would not be struggling for water. Today, in Punjab, 9 to 10 government and private power plants burn about 4.38 million tons of coal each year, producing 1.46 million tons of hazardous radioactive uranium, which causes cancer and other diseases among Punjabis. Today, because of these power plants, Punjab’s soil, water, and air are so polluted that out of 138 blocks, 110 have been declared dark zones. Now, Punjab is known as the cancer capital of India.

Punjab is importing coal from other states, and according to a NASA report, Punjab is heading towards becoming a desert. Today, Punjab’s government has been pleading with the Centre to waive farmers’ loans. We all know about suicides by Punjab’s farmers.

In December 2019, Himachal Pradesh had signed an MOU to sell its share of Yamuna water to Delhi at 21 crores rupees per annum. But Haryana opposed Himachal Pradesh’s plan to sell its share of Yamuna water to Delhi, contending that its “canals did not have the capacity to carry extra water from Himachal Pradesh to Delhi.” Thereafter, Himachal Pradesh also backed out from the agreement. It shows that some Indian states could wriggle out of their agreements subsequently due to political or other reasons. However, Punjab was never allowed to cancel its river water agreements with some states when it realized that the concerned agreements were against the interests of Punjab.

The Centre as well as several states undoubtedly wanted to harm Punjab, but Punjab’s own political leaders did not hold back either. If our own leaders had not sacrificed Punjab’s future for their personal interests, billions and trillions of rupees could have been spent on Punjab’s development . Even though it is already is too late, Punjab’s political leadership should come forward to fight valiantly for it’s just rights.

Before the 2016 assembly elections in Punjab, the Akali government had passed a resolution in the Assembly on 16 November 2016, stating that the Central government should be asked in writing to recover the price of water given to Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi. Who wrote this matter and what happened to it, no one knows. Such great resolutions are only passed when elections are very near, and everyone forgets about them after the elections are over. It is all just politics for votes, and nothing else.

Public Interest Litigation

In 2018, a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in the Punjab and Haryana High Court seeking a compensation of 80,000 crores rupees to Punjab for supplying river water to Haryana and Rajasthan for free for more than 70 years. The PIL sought setting up of an independent authority for calculating the costs for supplying Punjab’s river water to Haryana, Chandigarh, Rajasthan and Delhi.The PIL had been filed by 19 persons, including MP Dharamvir Gandhi and former High Court judge Justice Ajit Singh Bains. In their plea, the petitioners stated that Punjab is deficient of water and even the groundwater stands depleted in at least 14 lakh tube well areas. The petitioners sought the quashing of the 1995 Government of India’s decision to allocate Punjab’s river water to Rajasthan and other non-riparian states.

The Punjab government has supported the claim that an initial 1955 decision mentioned that the allocation of water cost would be taken up separately, but that never happened.

Narendra Modi, Amit Shah and Bhagwant Singh Mann

At his election rallies in Punjab in November 2016 and January 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had made the statement that Punjab ki dharti (land of Punjab) should get the advantage of additional river waters. He had mentioned that the water from the Indus, Sutlej, Beas, and Ravi rivers, over which India had a right under the Indus Waters Treaty, was flowing into Pakistan without being fully utilised in India. He had promised to stop this ‘wasted’ water from going to Pakistan, and instead divert it to the farmers of Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir.

In response to the horrifying terror attack in Pahalgam on 22 April 2025 where 26 innocent Indians were gunned down, India suspended the Indus Waters Treaty. Home Minister Amit Shah stated that after suspending the Treaty, the river water flowing to Pakistan would be diverted through new canal systems primarily to Rajasthan. (From the time of Nehru till now, India’s successive Central governments have gone out of the way to provide excessive volumes of Punjab’s river waters to Rajasthan while adopting a step-motherly attitude towards Punjab. While special efforts have been continuously made by the Centre to transform Rajasthan’s desert areas to green lands, direct and indirect efforts have been regularly made to convert Punjab’s green fields into desert or semi-desert areas). From Amit Shah’s statement, it appears that after suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty by India, some volumes of river waters can also be diverted to Haryana and Delhi. While Punjab deserves to be the main beneficiary because it has immensely suffered in the past, it appears that Punjab might get very little volume of the river water. Punjab Chief Minister should take up this matter forcefully with the Centre without any delay.

It is a matter of satisfaction that at the Punjab’s special Vidhan Sabha session convened in May 2025, the opposition parties fully supported the Aam Aadmi Party’s resolution to reject Haryana’s demand for additional water via the contentious Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal. Punjab has repeatedly asserted that it has no spare river water to give to Haryana. At a meeting between the Chief Ministers of Punjab and Haryana held in October 2025, Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Singh Mann proposed an alternative solution – utilising water from the Chenab river (a western river previously allocated to Pakistan) to address the water-sharing conflict between the two states while shelving the SYL Canal project altogether. He urged the Centre to divert the Chenab river’s water to Indian dams like Ranjit Sagar, Pong, and Bhakra, emphasizing the need for new canals and infrastructure in Punjab. He suggested using water from the Chenab river, arguing that it could be shared with Haryana and other states also, which would make the SYL Canal project unnecessary. It is an amazing proposal and the Centre should pressurize Haryana to accept it. Punjab should also put pressure on Haryana to share its Yamuna river water with Punjab.

Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Singh Mann should seek unwavering support of the leaders of all political parties of Punjab for the permanent solution of Punjab’s river water crisis. If water flowing to Haryana, Delhi, Chandigarh and Rajasthan cannot be fully stopped, then their volumes should be significantly reduced. Also, Haryana, Delhi, Chandigarh and Rajasthan should be compelled to pay Punjab for using its river waters (one cusec of water is worth more than one crore rupees), similar to how states are compensated for other natural resources like minerals.

A high power delegation consisting of Chief Minister Mann, Punjab’s other important political leaders, and the state’s top concerned ministers and bureaucrats should meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi. All relevant facts and figures regarding grave injustices done to Punjab relating to its river waters should be properly explained to him. After suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty by India, Punjab’s river waters have almost stopped flowing into Pakistan. All such river waters will obviously be used by India now. As Punjab has suffered too much in the past, it should be ensured that Punjab would be the major beneficiary now.

If, unfortunately, Punjab’s high power delegation fails to get a suitable response from the Prime Minister, then the Punjab Government should avail the services of India’s top lawyers to get justice from the country’s Supreme Court.

Acknowledgement: The scribe has liberally used facts and figures mentioned in several newspaper reports and articles, but he particularly wishes to express his gratefulness towards Dr. Malkiat Singh Saini (Former Dean, Academic Affairs, Punjabi University, Patiala) for using exhaustive information contained in his amazing article that was published sometime back.