It began not in a temple, nor in a lecture hall, but in the quiet curiosity of reading. As a student of both philosophy and faith, I picked up a book on Hermetic alchemy, not expecting it to speak to my Sikh upbringing, but intrigued by the ancient mysticism it promised. What I found was startling: as I read the cryptic lines of the Emerald Tablet, a foundational Hermetic text, I felt as though I was reading echoes of Guru Nanak's Mool Mantra. It was not a perfect match; the metaphors, language, and historical settings were different — but the resonance was undeniable. This personal encounter spurred me into a deeper inquiry: how could a Hellenistic esoteric text and a 15th-century Punjabi spiritual revelation converge so profoundly on key ideas of unity, transformation, and divine realization?

The Emerald Tablet, attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, succinctly encapsulates Hermetic thought in a few enigmatic lines. Its most quoted maxim, “As above, so below,” proposes a metaphysical symmetry between the internal and external worlds — a reflection of divine order mirrored in both the cosmos and the self. ¹ The text emphasizes that all things come from a single source and can return to that source through inner refinement. This principle is central to Hermetic mental and spiritual alchemy, where the self is transmuted like metal: gross elements of ego, illusion, and fragmentation are purified into unity, insight, and divine alignment. ²

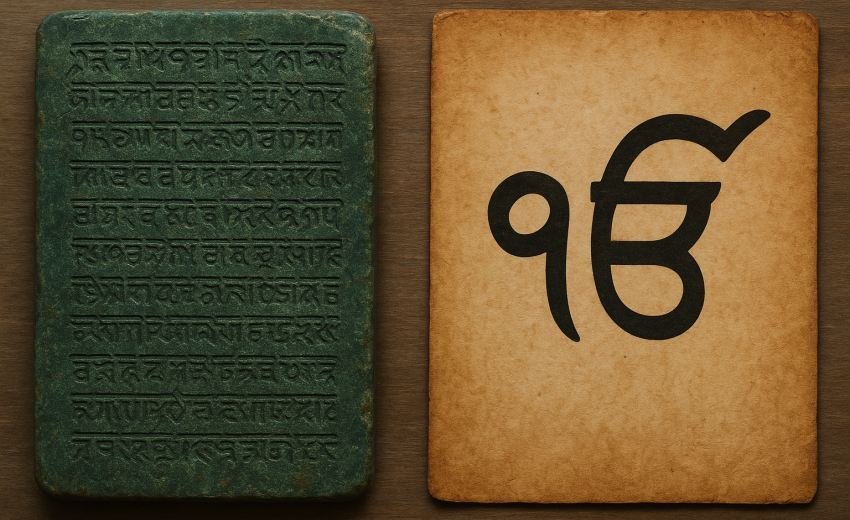

Guru Nanak’s Mool Mantra, the opening verse of the Guru Granth Sahib, provides a foundational Sikh theological vision. It begins with Ik Onkar — the affirmation that all existence is One — and continues with attributes of this Oneness: Sat Naam (Truth is Its Name), Karta Purakh (Creator Being), Nirbhau (Without Fear), Nirvair (Without Hatred), Akaal Moorat (Timeless Form), Ajooni (Unborn), Saibhang (Self-Existent), and Gurprasad (Realized through the Guru’s Grace).³ For Sikhs, this mantra is not only a metaphysical description but also a spiritual instruction: to live in remembrance of the divine, in harmony with truth, and in surrender to the eternal.

The similarities between these two texts are not superficial. Both insist on the absolute unity of all existence, not just as theology, but as lived metaphysics. The Hermetic phrase “all things have come from the One, by the mediation of the One” ⁴ resonates with Nanak’s concept of Mool Mantra. Both reject dualism. Where Hermeticism proposes that spirit and matter are expressions of the same divine order, Sikhism emphasizes the inseparability of Creator and creation (Ik as both immanent and transcendent).

Critically, however, the method and tone of each tradition reveal key distinctions. The Emerald Tablet presents its wisdom in veiled, symbolic language, suited to esoteric initiates and mystics. Its alchemical metaphors require decoding, often placing the burden of interpretation on the reader's intuition and discipline. Sikhism, by contrast, speaks plainly, compassionately, and communally. Guru Nanak did not reserve truth for the elite but walked among farmers and kings alike, offering Naam (the divine Name) as the path to liberation. ⁵

Still, the impulse at the heart of both systems is profoundly aligned. Each presents the human self as malleable and divine in origin, capable of refinement and transformation. In Hermetic alchemy, the process is metaphorical: turning lead into gold, ignorance into wisdom. In Sikhism, the process is spiritual: dissolving ego (haumai), practicing seva (service), and attuning to divine will (hukam). The result is the same — an awakened consciousness that reflects the divine unity underlying all things.

What struck me most as a critical reader is how these traditions — divided by centuries, geography, and language — converge on such deep metaphysical truths. This is not accidental. It suggests that spiritual wisdom may emerge universally in response to the same human condition: the tension between the finite and the infinite, the self and the cosmos. While we must avoid collapsing these systems into one another or ignoring their differences, we should also resist the temptation to keep them in separate silos.

There are clear contrasts. Hermeticism leans toward secrecy, symbols, and personal enlightenment, while Sikhism emphasizes devotion, community, and ethical action. One may risk spiritual elitism; the other insists on radical equality and divine grace. Yet both begin with Oneness and end in transformation. Both suggest that self-knowledge is not vanity but the key to universal knowledge — and that through inner work, the divine becomes not only knowable but lived.

This encounter between the Emerald Tablet and the Mool Mantra deepened my appreciation for both. It reminded me that wisdom, though shaped by context, transcends boundaries. What I first saw as spiritual coincidence now feels like a universal echo — a reminder that the truths worth seeking are often spoken across many tongues. And in those echoes, we begin to transform.

References

- Holmyard, E.J. Alchemy. Dover Publications, 1990.

- Hall, Manly P. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Philosophical Research Society, 2003.

- Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus. HarperCollins, 2001.

- Waite, Arthur Edward. The Hermetic Museum, Restored and Enlarged. Kessinger Publishing, 1999.

- McLeod, W.H. Guru Nanak and the Sikh Religion. Oxford University Press, 1996.