|

October 15, 2012. VRINDAVAN, India — Lalita Goswami was married only a few years when her husband, a Hindu priest who beat her and abused drugs, died of an apparent overdose. She was left with three young children.

Still, she said, being married was better than being a widow.

That ordeal has lasted for decades. After her husband died, the brother-in-law who took her in kicked her out, forcing her back to her parents' home in Kolkata. Her brother saw her as a financial burden and neighbors ostracized her. In a bid to keep peace, her mother exiled her and her two youngest children to Vrindavan in central India, a sacred town known as the City of Widows.

Today, nearly 15,000 widows live in Vrindavan, where the Hindu god Krishna is said to have grown up. Although it is believed they were first drawn for religious reasons centuries ago, many widows now come to this city of 4,000 temples to escape abuse in their home villages — or are banished by their husbands' families so they won't inherit property.

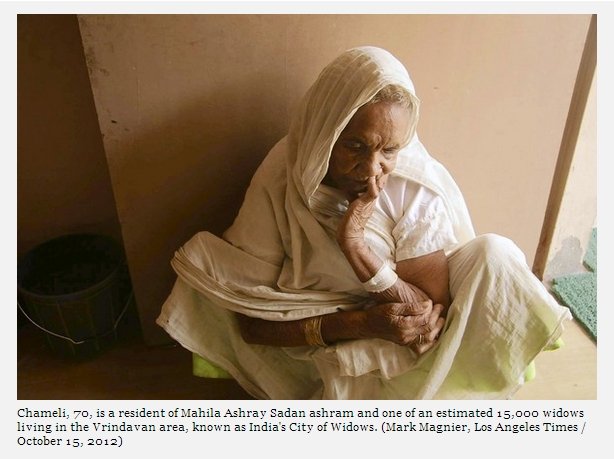

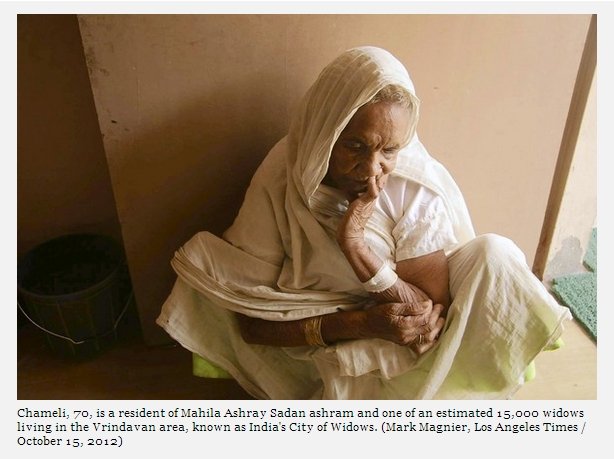

Goswami spends her time at Mahila Ashray Sadan, one of several widow ashrams supported by charities here.

"What else could I do?" said Goswami, a solicitous woman who strokes visitors' faces and touches their feet in a traditional sign of respect. She lives in a 30-bed dormitory laced with the widows' meager possessions.

Goswami recently lost her appetite and suffers from chronic diarrhea and nausea. The ashram gives her one meal a day and a $6-a-month allowance. Healthcare is scarce. "I'm 70, maybe 80," she said. "All I know is, my children have children."

For centuries, Indian widows would throw themselves on their husbands' funeral pyres, reflecting the view that they were of little social worth without their protector and breadwinner. Although that practice, known as sati, has been outlawed, widows are still traditionally considered inauspicious, particularly in Bengali culture, their presence at weddings and festivals shunned and even their shadows seen as bad luck.

Until a few decades ago, widows were often accused of causing their husbands' deaths — the mother-in-law in older Hindi films would accuse the new widow of "eating her son" alive. Even now, "unlucky" widows are scorned for remarrying, views reformers attribute more to India's male-dominated society than religious tenets.

"Widows are treated like untouchables," said Bindeshwar Pathak, head of the civic group Sulabh International. "Indian tradition is very full of heritage and knowledge, but some of our traditions are beyond humanity."

In August, an outraged Supreme Court ordered government and civic agencies to improve the lives of women in Vrindavan after local media reported abandoned corpses being put in sacks and tossed into the river, a charge officials deny. The government of West Bengal state, where most widows who live here come from, has since promised to provide them with government housing and a stipend exceeding what they'd receive in Vrindavan, which is in Uttar Pradesh state.

But social workers, pointing to similar past initiatives, say follow-through is often lacking. Nor is it clear that the widows want to leave Vrindavan, said Yashoda Verma, who manages the 160-resident Mahila ashram.

According to centuries-old Hindu laws, a widow hoping to obtain enlightenment should renounce luxuries and showy clothes, pray, eat a simple vegetarian diet (no onions, garlic or other "heating" foods that inflame sexual passions) and devote herself to her husband's memory.

At least, that's the idea.

"Very rarely do you see people go to Vrindavan because they're devoted to the cause," said Rosinka Chaudhuri, a fellow at the Center for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. "Sometimes it's blackmail, or if you're not loved enough, you take yourself up. But the numbers are staggering."

Guddi, a resident in her 70s with a square face and a nose ring, said she came to Vrindavan after being abused by her daughter-in-law, a common complaint.

"What's the point if they feed me two rotis [flatbread] but beat me with a shoe?" said Guddi, who uses one name. "If I'd been born a man, life would've been better. There isn't much respect for women in India."

But social and generational changes are also evident. Even as prejudices linger in rural areas, a growing number of widows in urban areas or those from less-restrictive families remarry — sometimes to a brother-in-law — maintain careers and share the inheritance.

All widows over 60 are eligible for a $16 monthly government pension and food allowance. But up to 80% are illiterate and unable to navigate India's labyrinthine bureaucracy. Even those who do succeed complain that inefficiency and corruption siphon off some of their money.

Many supplement their income by chanting up to five hours a day at local temples — essentially singing for their supper — in return for 10 cents and a bowl of rice. Goswami gave that up when her health deteriorated.

Activists argue that policies should aim to make the widows financially independent rather than depending on minuscule handouts.

But others point out that some widows can earn a decent living at Vrindavan. Goswami's ashram forbids begging, but widows who live independently can earn up to $150 a month begging from the half-million pilgrims visiting each year.

The ashram believes begging is a social evil, particularly when residents' basic needs are covered. Verma, the ashram's manager, said some Vrindavan residents aren't really widows and use the earnings to support families back home.

In India, trained priests from lower caste still awaiting jobs

India to open door to foreign investment in some sectors

In India, emu scheme leaves behind distraught investors, birds

Ads by Google

"Many are faking," she said, adding that her ashram informally vets newcomers to limit the abuse. "Some lie for a nice place to live."

In sharp contrast with a nearby six-lane highway and new gated communities with names like Omaxe Eternity and Hare Krishna Residency, some of the government- and charity-run ashrams evoke the Victorian era.

Mahila's residents appear relatively comfortable, but at an adjoining ashram run by another civic group, bugs course across the floor, a diesel smell fills hallways that lead to dilapidated rooms and the plumbing is broken.

Goswami took a circuitous path to her ashram. On reaching Vrindavan with her two toddler sons — the in-laws kept her daughter, whom she never saw again — she said she worked for several years as a cook and maid until she was injured when a monkey attacked her, causing her to fall two stories.

One son went insane after "a girl from Bombay put a hex on him," she said, while the other followed his father into the Hindu priesthood. "He makes good money," she said. "But he's thrown me away."

Goswami said she thought about killing herself when she was widowed but resisted, given her responsibilities. "Sometimes I wish I'd committed sati," she said. "I didn't because of my sons, and look how they treat me."

As she spoke, she looked around the crowded dormitory decorated with images of Hindu gods. "The fact of it is," she said, "widows are doomed."

Tanvi Sharma of The Times' New Delhi bureau contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2012, Los Angeles Times |