It's not often that bathroom selfies go viral.

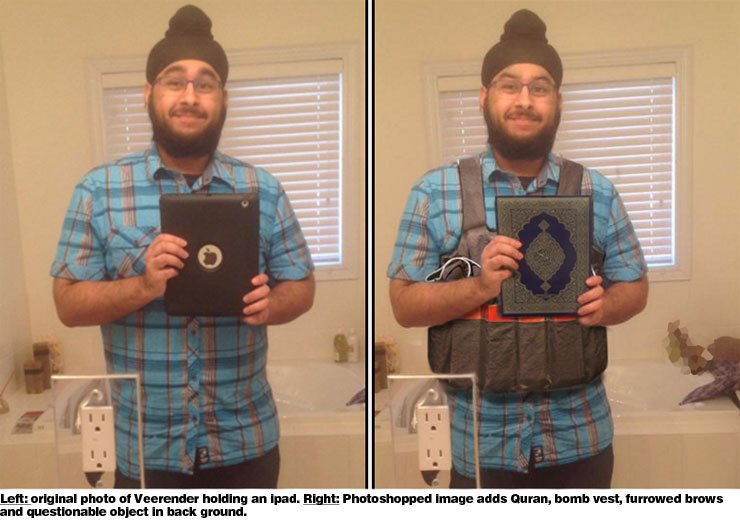

But last week, a picture of a man posing with a Koran and wearing a suicide vest went viral after some social media users claimed it was taken by one of the Islamic State terrorists that attacked Paris.

The only problem: It wasn't a terrorist but a young Canadian Sikh man named Veerender Jubbal.

The image was posted to several online news sites. And Jubbal's face appeared on the front page of Spain's La Razón newspaper with a caption labeling him "one of the terrorists."

Eventually, the media outlets posted retractions, and tweets circulated showing the original selfie next to the doctored image.

The suicide vest was fake, and the Koran was an iPad.

We've got to continuously explain that we are not Muslims -- but then say that even if we were, anti-Muslim animosity is unacceptable.- Simran Jeet Singh, senior religion fellow of the Sikh Coalition

Had any of the news outlets had even one Muslim or Sikh (or just someone who had a good Muslim or Sikh friend) working on the story, this could have been avoided. Even if you ignore the sex toy photoshopped in the background, there are too many things that point to the image being a fake.

Jubbal's patka, with a top knot, is unique to Sikh culture. It doesn't look like an Arab turban. And no matter how powerful or dangerous you may believe the Koran to be, it is similar to the Bible in that it can't take selfies.

But none of that mattered because the person who tweeted the photoshopped image likely knew that our ignorance of Muslims would result in us jumping to conclusions.

Despite data showing that, since 9/11, white Americans have committed the largest number of ideology-based attacks in the U.S., our collective imagination of what a "terrorist" looks like is a "Muslim." And because we don't know much, and don't seem to want to know much, about Islam — "Muslim" is often a code word for "brown."

Simran Jeet Singh, senior religion fellow of the Sikh Coalition, says that like many other groups that "look Muslim," Sikhs are often put in a dangerous position when attacks

"We've got to continuously explain that we are not Muslims — but then say that even if we were, anti-Muslim animosity is unacceptable," Singh explains. "It's a two-step process."

This process has become a sad reality for brown people across America.

In September, a Chicago Sikh named Inderjit Singh Mukker was hospitalized after being beaten unconscious. His assailant reportedly called him "terrorist" and "Bin Laden" and told him to "go back to his country." Mukker is a U.S. citizen who had been in the country for 27 years — longer than his assailant has been alive.

Last week, four people were removed from a plane when a woman reported "suspicious behavior" of one of the passengers. His crime? He appeared to be of "Middle Eastern descent" and he was watching the news on his phone.

The same day, an Uber driver picked up a passenger from a bar in Charlotte, N.C. The passenger asked if his driver was Muslim, and then beat him and threatened to kill him. The driver is a Christian from Ethiopia.

In moments of intense tragedy ... we see major spikes in hate violence against people who are viewed to be the enemy.- Simran Jeet Singh, senior religion fellow of the Sikh Coalition

Anti-Muslim sentiment knows no sacred boundaries. A Hindu temple in Ontario, Canada, had its windows smashed last week, while the head priest attended a vigil for the victims of the Paris attacks. In 2013, a vandal spray-painted "terrorist" on a Riverside Sikh temple — about a year after a man shot and killed six Sikhs at a Wisconsin temple.

In each situation, a community is forced to once again explain who they are and to denounce bigotry against a group they are not members of.

It's not difficult to connect the dots. "Muslim" is not a race — except in our imaginations.

"In moments of intense tragedy ... we see major spikes in hate violence against people who are viewed to be the enemy," Singh says. "Anybody who is Muslim, or appears to be Muslim, is subjected to serious violence." Because of this, Muslims — and anyone who "looks" like one — can feel pressure to preemptively denounce terrorism, so that we can know they're one of the "good ones."

It's especially important to note these trends when the nation is also talking about race-based micro-agressions that people of color face on a daily basis. The photoshopped image of Jubbal was produced well before the Paris attacks and was circulated among followers of Gamergate: a group of video game fans primarily known for misogyny, homophobia, racism and cyberstalking. They seem to have thought the doctored image was funny.

"Cases like [Jubbal's] demonstrate to us that there's no such thing as harmless racism," Singh says. "I know that people justify micro-acts of racism as being jokes, but you can see that every negative moment of racism perpetuates stereotypes, and that leads to serious consequences."

In this case, innumerable micro-acts of racism led to a young man's life being put in danger. Allowing Islamophobic jokes and abuse to go unchecked likely encouraged the Gamergate mob mentality that thought circulating a fake photo of Jubbal was an appropriate way to punish him for criticizing them.

These micro-acts of racism are also what have paved the way for more than half of U.S. governors and now some mayors, who are attempting to block Syrian refugees from entering their states or cities — even though such measures are likely unenforceable andprobably illegal.

Islamophobia, no longer just the purview of the powerless or the uneducated, is now a staple of a presidential platform. Donald Trump called Syrian refugees "the Trojan horse" and wants surveillance of certain mosques — even after walking back what many perceived as a suggestion for a mandatory registry. Ben Carson warned of "bad apples" among the refugees, after toning down a "rabid dog" analogy in describing how he'd handle incoming refugees. And Ted Cruz suggested that the U.S. should accept Christians from Syria but not Muslims. We sometimes ask our politicians to be more subtle with their speech, but in general we allow this fear-mongering to continue.

In a statement, Jubbal wrote that he sees the photoshop hoax as "an opportunity for all of us to hopefully grow together in our shared understanding for one another."

But as we begin that process, before we can grow together, we're going to have to acknowledge that the burden should not be on Muslims to apologize for the actions of terrorists, or for brown people to repeatedly educate us on their backgrounds. These communities are already showing patience, kindness, and compassion towards their fellow Americans.

It's the rest of America that needs to grow up.