|

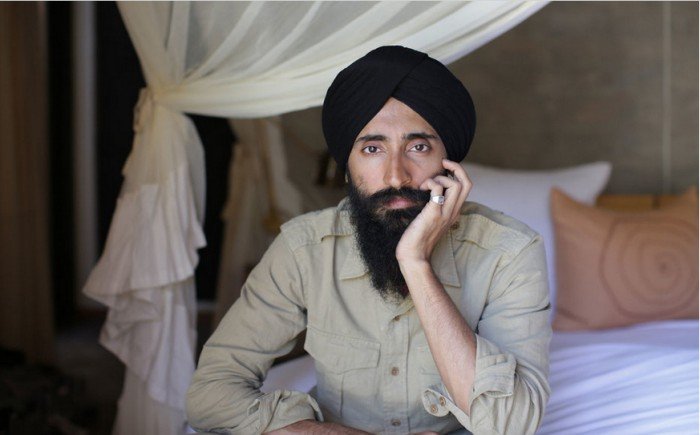

| Christopher Wray-McCannWaris Ahluwalia |

Here, the actor and designer talks with Travel + Leisure about security policies and travel as a means of cultural exploration.

February 16, 2016: Waris Ahluwalia, an Indian-American actor and fashion designer, took a public stand last week against religious discrimination in airport security after Aeromexico officials prohibited him from boarding his flight home to New York.

Ahluwalia had declined to remove his turban—or dastaar, an important garment in the Sikh religion—in public during a secondary security screening at Mexico City’s Benito Juarez International Airport. Though this was Ahluwalia’s right under Transportation Security Administration guidelines, the Aeromexico employee informed him he would not be allowed to board and should instead travel on another airline.

After a days-long social media campaign and negotiations led by the New York-based Sikh Coalition, Ahluwalia won both an apology from Aeromexico and a promise to strengthen employee training on screening religious headwear. But the incident reveals serious institutional gaps when it comes to a consistent protocol balancing airport security with human rights. It also demonstrates the breakdown of customer service when a passenger—even an actor from films like The Grand Budapest Hotel—lands on the secondary security screening list.

“This is not about Aeromexico,” Ahluwalia tells Travel + Leisure. “This is about every airline.”

Upon check-in at the Mexico City airport on Monday morning, Ahluwalia was selected for secondary screening—a familiar situation for Ahluwalia, who jokes that he’s managed to defy all the odds in being repeatedly selected for the purportedly random system. He passed through a metal detector at airport security without any problems, and reported to his gate. That was where the trouble began.

As expected, an employee at the gate noticed the secondary screening selection on Ahluwalia’s boarding pass and asked him to step aside. Once everyone else had boarded the flight, Ahluwalia went through the pat down and swabbing procedures that are standard for airport security screening. But then the employee told him to remove his turban.

That’s not supposed to happen. Years ago—under pressure from the Sikh Coalition—the TSA revised its guidelines to declare that Sikh travelers have a right to wear turbans. These guidelines make clear that asking a traveler to remove a turban is a last resort that comes if a pat down or screening with a metal detector wand triggers an alarm. In that case, security agents are supposed to offer a private screening room for the passenger to remove his turban.

Of course, the TSA was not the agency in play here—and that’s part of the problem. Gurjot Kaur, senior staff attorney for the Sikh Coalition, says it was unclear who was in charge of this secondary screening and whether that agency had any established protocol for screening religious headwear. There’s also some question of how foreign airlines are expected to apply the guidelines that TSA mandated for all in-bound flights after 9/11. Sure, global travelers have to abide by liquid rules, for example, but Kaur says that “we want to make sure [TSA is] exporting the human rights part of it, too.”

A note on the turban: in Sikhism, it is a symbol of equality, piety, courage, and justice. It was a reminder to the wearer to represent those virtues and a message to the rest of the world that he would uphold them. As Ahluwalia explains it, historically if you were in trouble and saw a Sikh man wearing a turban, “that’s who you’d run to for help.” So wearing a turban is a cherished part of the faith and removing it requires privacy. “A turban is not like a pair of shoes,” Kaur says, further noting that these private rooms should also be equipped with a mirror. Turbans are not exactly hats. They are tricky to wrap.

Since 9/11, the Sikh Coalition has uncovered a tremendous number of violations of Sikh religious liberties during air travel, Kaur says. Complaints from domestic travelers have gone down since the TSA implemented its new guidelines toward religious headgear in 2007, but the problem persists and is especially pernicious when it comes to this inconsistently regulated sphere of foreign airlines flying into the United States. Kaur says the Sikh Coalition is drafting a letter to the TSA to ask for clarity on this issue and to ask them to ensure American security policies also be applied to anyone flying into the U.S. “What happened with Waris was an important wake-up call for all airlines that fly into the United States and even airlines here in the United States and airport screening officials,” Kaur says.

But Ahluwalia says that what he faced in Mexico was not just an institutional failure but also a customer service failure. When he landed on that secondary security-screening list—and every time he lands on that secondary security-screening list—he was treated differently. Airports are high-pressure environment so he doesn’t exactly expect to get service with a smile, he says, “but when you get the SSSS people treat you like you’ve already done something.” He argues that he’s not looking for special exemptions or security lapses—after all, he half-jokes, he’s going to be on that plane, too—but he wants to be treated with humanity when he travels. “We’re the consumer,” he says. “If we don’t fly, the airline ceases to exist.”

Ahluwalia points out that there’s a real irony in this deficiency of cultural understanding that at times rears its head at airport security. “Why do we travel? We travel to explore other cultures, to be immersed in other cultures,” he says. “Travel is an amazing tool for understanding and an airport is the portal.”

He chose to stand up and protest his treatment as a way to further that understanding. After he was turned away at the gate, Ahluwalia tweeted and Instagrammed his experience, causing a furor both in social and traditional media. Aeromexico executives promptly apologized and offered him a boarding pass for the next flight to New York. But Ahluwalia refused. “I knew if I got on that plane that this would happen to someone else,” he says. “I couldn’t do that.” Instead, he stayed in Mexico City for another two days while the Sikh Coalition pressed Aeromexico into agreeing to the awareness training.

“Part of the conversation was explaining their religious rights infringement,” Kaur says. “Aeromexico was obviously very sympathetic and issued an apology immediately, but we wanted to make sure it wasn’t a one-off type of incident everybody forgot about. We wanted to use it as a tool to make sure that it doesn’t happen again.”

Ahluwalia also stresses that he’s not holding any grudges against Aeromexico—a sentiment illustrated in the Instagrammed photo he took with the pilots on his successful return flight on Wednesday. “I celebrate Aeromexico for committing to do this,” Ahluwalia says. He’s told his fans in Mexico not to apologize for the incident either. It’s not about that, he says. It’s about standing together.

In that respect, Ahluwalia encourages other travelers to stand up for themselves when facing discrimination at the airport, offering two rules: remain calm while talking with airport officials, and always remember that you have a voice, even if you don’t have the platform of an actor and fashion designer. Thanks to Twitter and Instagram, he says, “we’re no longer left with no option.” The Sikh Coalition also has a FlyRights app for iPhone and Android that allows all travelers—Sikh or non—to easy file complaints of discrimination.

And Ahluwalia says it’s on other travelers, too, to help curb discrimination in airports by telling the authorities what you’ve witnessed and that you find it unacceptable. While an airline might ignore one person tweeting about a bad experience, they’re unlikely to ignore 10 passengers tweeting in support of that one person. “You’re bonded, you’re travelers, you’re explorers,” Ahluwalia says. “You look out for each other.”