A growing middle class in lesser-known towns presents a huge opportunity to marketers

|

| From Left: Hugh Sitton/Corbis; Shailesh Ravel/India Today Images; A Prabhakar Rao/The India Today Group/Getty Images; Adeel Halim/Bloomberg; Namas Bhojani/Bloomberg |

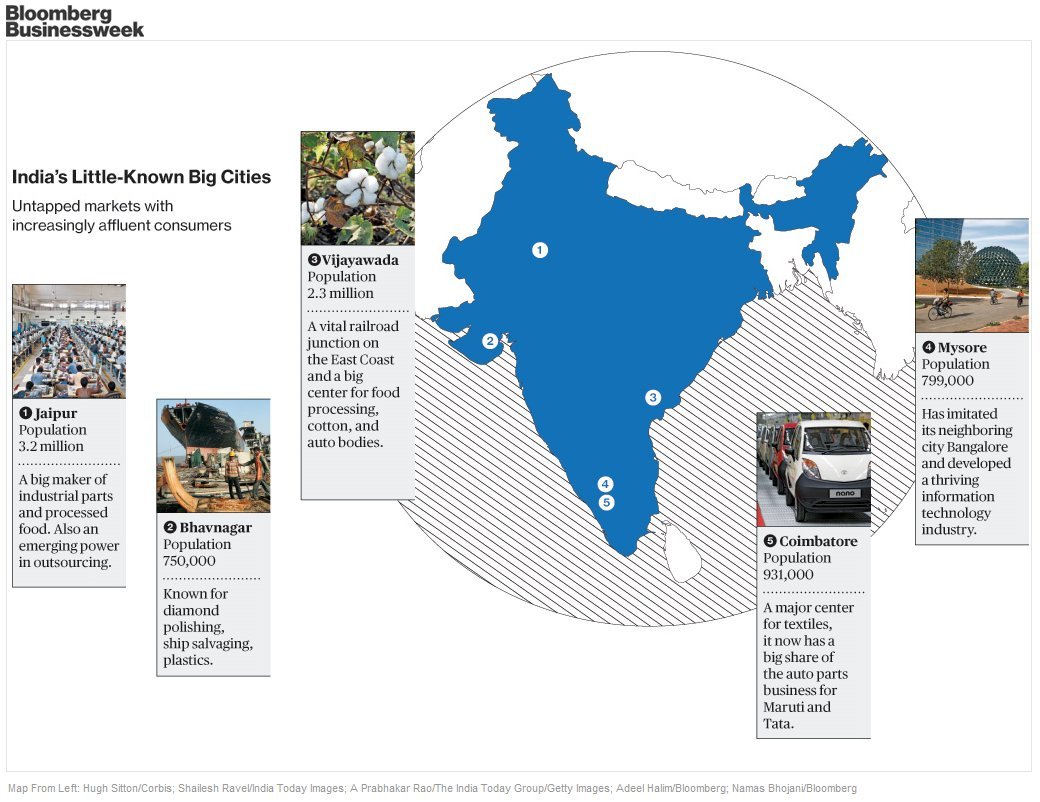

| India's Little-Known Big Cities ~ Untapped markets with increasingly affluent customers |

Sep. 30, 2010: Ever heard of Aurangabad, a dusty trading town in the heart of India? Neither, it seems, had Daimler (DAI), the No. 2 maker of luxury cars. So when a Mercedes-Benz dealership in Pune, a six-hour drive away, got a call from Aurangabad's chamber of commerce to place an order for 115 sedans, the sales clerk thought it was a joke.

It wasn't. In the last 10 years, Aurangabad has doubled in population to nearly 2 million, as Western companies such as engineering giant Siemens (SI) and brewer SABMiller built plants there and as Mumbai manufacturers found affordable sites for new factories. "Aurangabad has grown like anything, and people still thought of Aurangabad as this nothing town," says Sacheen Mulay, president of the local chamber of commerce and industry and a multimillionaire from his real estate projects. The idea for ordering en masse was cooked up by members of the chamber of commerce to get some attention for the new Aurangabad. "This is a place of potential buyers, new-generation entrepreneurs. People should take notice of that," says Mulay.

Daimler took note after Mulay and his colleagues went down to Pune with a PowerPoint presentation. The carmaker ultimately sold 148 autos to Aurangabad customers, the largest order in Asia, the company estimates. "We're clearly focused on these tier-two cities," says Wilfried Aulbur, chief executive officer of Daimler's India unit, who got involved personally in completing the order.

Most multinationals build a large presence in the top 10 cities of emerging-market countries such as Brazil, China, India, and Indonesia, so Rio, Shanghai, Delhi, and Jakarta get their state-of-the-art autos, cell phones, and retailers. Yet this focus comes at a cost. In a survey of multinationals, Boston Consulting Group found that most of the companies ignored cities with smaller populations and less apparent potential. Cities such as Aurangabad, Curitiba in Brazil, Xiaochang in China, and Yekaterinburg in Russia get lumped together, BCG found, with the mostly poor, rural populations that few companies, with notable exceptions such as Unilever (UL), are eager to pursue. "The next billion consumers, who are far above the poverty line, have high consuming power, and they are just not coming onto people's radars," says Sharad Verma, a partner at BCG.

Cities with fewer than 5 million residents make up 83 percent of emerging markets' urban consumers, BCG estimates. By 2030, 1.3 billion more people will live in emerging-market cities, driving 67 percent of global gross domestic product growth. Fewer than a fifth of these consumers will live in megacities such as Mexico City. The rest, who will be able to afford new cars, iPhones, and flat-screen TVs, will be spread out among 1,100 cities with populations over 500,000, up from 717 such cities today. Some 460 million people, earning $5,000 to $10,000 a year, will join the middle class in the next five years.

In the few smaller towns where the world's top marketers do show up, the impact is immediate. Amritsar, a town in Punjab best known for the Sikh Golden Temple, is now a thriving trading center for rice and wheat. The Indian conglomerate Bharti teamed up with Wal-Mart (WMT) to build the Arkansas retailer's first Indian store in Amritsar. Last summer, when reporters were given a tour, a traffic jam stretched a kilometer and a half down the road as farmers in tractors and Amritsaris in BMWs thronged the entrance.

Car sales are a good indicator of how much companies can gain from these towns, says Deepesh Rathore, managing director of IHS Global Insight India (IHS). Indians love cars, a visible marker of prosperity and a necessary purchase in places with little or no public transport. Yet General Motors' Chevrolet brand has less than 5 percent of the Indian market, even with eight models ranging from cheap to very expensive. "The most successful car for GM sells 4,000 units a year, which compares to a moderately selling car for Maruti Suzuki, the market leader," says Rathore. "GM has such a limited sales and service network that there's a big chunk of the population they just can't tap." Maruti has 802 sales centers in 555 cities; GM has about 200, mostly in the bigger cities.

Some Indian companies are quickly moving into smaller towns. PVR Cinemas, a Gurgaon-based chain whose shares have risen 75 percent since 2009, is betting its future on places most people can't find on the map—towns such as Nanded, Ujjain, and Vijayawada, says CEO Pramod Arora. "Smaller towns and cities offer immense opportunities, where the consumer base will grow at a phenomenal rate, while the bigger cities will taper off," he says.

Today, PVR has 70 percent of its multiplexes in cities such as Delhi and Mumbai. In those markets most customers pay $6 to $10 to be ushered into slick lobbies, where ads on LCD TVs hawk popcorn and sandwiches. Some even pay $22 for a reclining leather seat and waiter service. In the next two years only half of PVR's screens will be in the big cities, says Arora. Smaller theaters with fewer frills, charging $2 to $4 in cities such as Latur, will soon make up most of PVR's sales. Margins are expected to go up as PVR adds Mumbai-like amenities and customers make enough money to afford higher prices.

Back in Aurangabad, the 148 Benzes are expected to arrive in October. The owners can then drive to the new $66 million mall, one of Asia's largest, which opens in a month under the management of India's Provogue, a men's apparel maker, and London-based Capital Shopping Centres Group, which owns nine of Britain's largest malls. Coimbatore, Indore, and Nagpur will get malls next, says Capital Shopping CEO David Fischel. On YouTube (GOOG), meanwhile, a 3D walkthrough of the Aurangabad mall triggers such comments as "It's really heaven come to our city" and "Bravo, we are waiting for it." Sounds like a sales opportunity.

The bottom line: Smaller cities in Indian and other emerging markets offer the next big growth opportunity for multinationals.

Srivastava reports for BusinessWeek from New Delhi.