|

| By Schalk van Zuydam, AP United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon speaks during the conference on climate change in Durban, South Africa, on Tuesday. |

The European "road map" toward a new accord that would take effect after 2020 is a centerpiece of negotiations among 194 countries at a U.N. climate conference in the South African coastal city of Durban.

It has been presented as a condition for Europe to renew and expand its emissions reduction targets under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which expires next year.

"We must be realistic about expectations for a breakthrough in Durban," said U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon as he opened the final ministerial stage of the two-week conference. "The ultimate goal for a comprehensive and binding climate change agreement may be beyond our reach for now."

Political differences, the worldwide financial crisis and a divergence of priorities among rich and poor countries are barriers to an agreement on a future negotiating path, Ban said. But he urged nations to resolve lesser issues.

"We must keep up the momentum," he said. "It would be difficult to overstate the gravity of this moment. Without exaggeration, we can say the future of our planet is at stake."

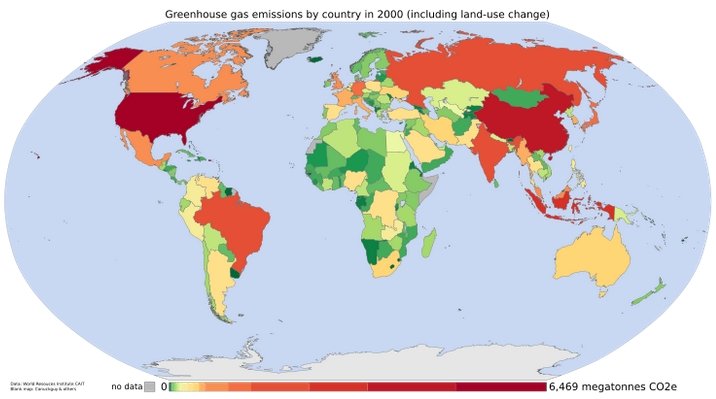

As the conference moved into high gear, EU and U.S. officials said that China made it clear in private meetings that it will not accept international limits on its carbon emissions in the future.

China has publicly stated it is willing to embark on negotiations on a legally binding post-2020 deal, but it has never explicitly stated that it would accept binding restrictions for itself.

"It is not my impression that there has been any change at all in the Chinese position in regard to a legally binding agreement," U.S. envoy Todd Stern told reporters after meeting with the Chinese delegation.

An EU delegate said that China unequivocally rejected the idea of assuming internationally binding limits on its emissions during a closed meeting on Monday with EU climate commissioner Connie Hedegaard.

The delegate spoke on condition of anonymity because the negotiations were still in an early stage.

China maintains that it is still a developing country with millions of impoverished people, despite its huge cash reserves. Most research also agrees with Beijing's contention that it is moving faster than most countries in closing dirty industries and developing clean energy.

As for the U.S., Stern said it was prepared to talk about the next phase of fighting climate change, but not to declare in advance that the objective is a legally binding treaty.

Such a goal would be difficult with Washington insisting any future agreement relate to all countries with equal legal force. Currently, industrial countries have legally binding emissions obligations, but any action by developing countries is voluntary.

"Some countries have projected the question of a legally binding agreement in the future as a panacea for climate change. This is completely off the mark," said Indian Environment Minister Jayanthi Natarajan, speaking also for China, Brazil and South Africa, the world's four fastest developing economies, known as BASIC.

"Developing countries should not be asked to make a payment every time an existing obligation becomes due on the part of developed countries," she said.

BASIC said it was essential that the industrial countries renew commitments to cut carbon emissions as laid out in the Kyoto Protocol, moving into what is described as a second commitment period beginning in 2013.

The U.N. chief urged the industrial countries to keep Kyoto alive, calling it the closest thing to a climate treaty.

"I urge you to carefully consider a second commitment period," Ban said, drawing applause for the only time in his 15-minute address to the 15,000 participants.

South African President Jacob Zuma said the dispute over continuing Kyoto was threatening other issues. If it is not resolved, he told the conference, "the outcome on other matters will become extremely difficult."

Also Tuesday, scientists and U.N. agencies reminded the delegates that carbon emissions were still climbing and the Earth still warming while they were seeking political solutions.

An international treaty on climate change wouldn't be enough to avert a dangerous rise in global temperatures, and countries need to voluntarily make deeper cuts in carbon emissions, said Achim Steiner, the head of the U.N. Environment Program.

A UNEP report, released last month and formally presented to the host government South Africa, said the world is losing ground in controlling heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

"We are not moving fast enough," Steiner said. "We are losing time."

© Copyright 2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.