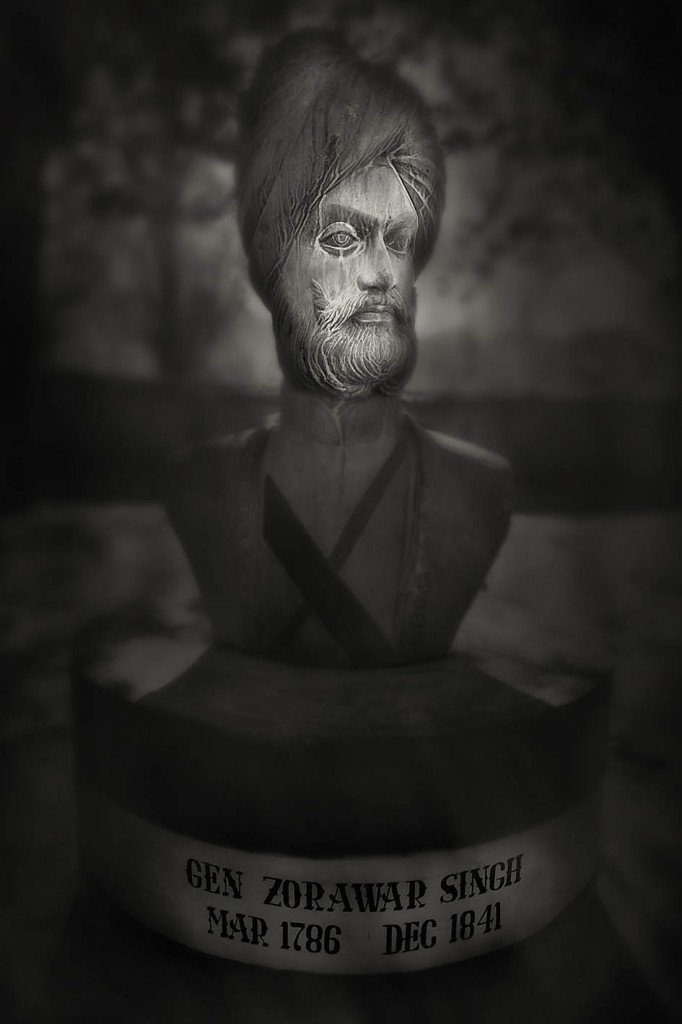

| Thirty years – In search of General Zorawar Singh (1786 – 1841) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hundreds of human skeletons, some with frozen flesh attached to them, can still be found around Roopkund (16,500 feet), a remote glacial lake in the lap of Trishul massif in Himalayas. The presence of these skeletons was first discovered in 1942 by the Himalayan ranger H K Madhwal.

I was fortunate to be schooled at The Doon School, Dehradun (India), an institution that valued the importance of growth by encouraging us to trek in the Himalayas. In 1983, when I was seventeen, a group of senior students successfully trekked to Roopkund, bringing samples of human bones. With a sense of curiosity, I asked my housemaster, Mr. Vaishnav, “Why are so many skeletons found around this remote lake?” Mr. Vaishnav replied, “These are believed to be the remains of General Zorawar Singh’s soldiers who got lost in the Himalayas while returning from the Tibetan plateau.” Who was General Zorawar Singh?

The plains of Indian sub-continent since 9th century had been continuously invaded, looted and ruled by many dynasties. It was only with the rise of the Sikh kingdom in Punjab, during the regime of Maharajah Ranjit Singh (1780 – 1839), the “Lion of Punjab”, this trend was reversed. Ranjit Singh’s military career can be divided into three phases.

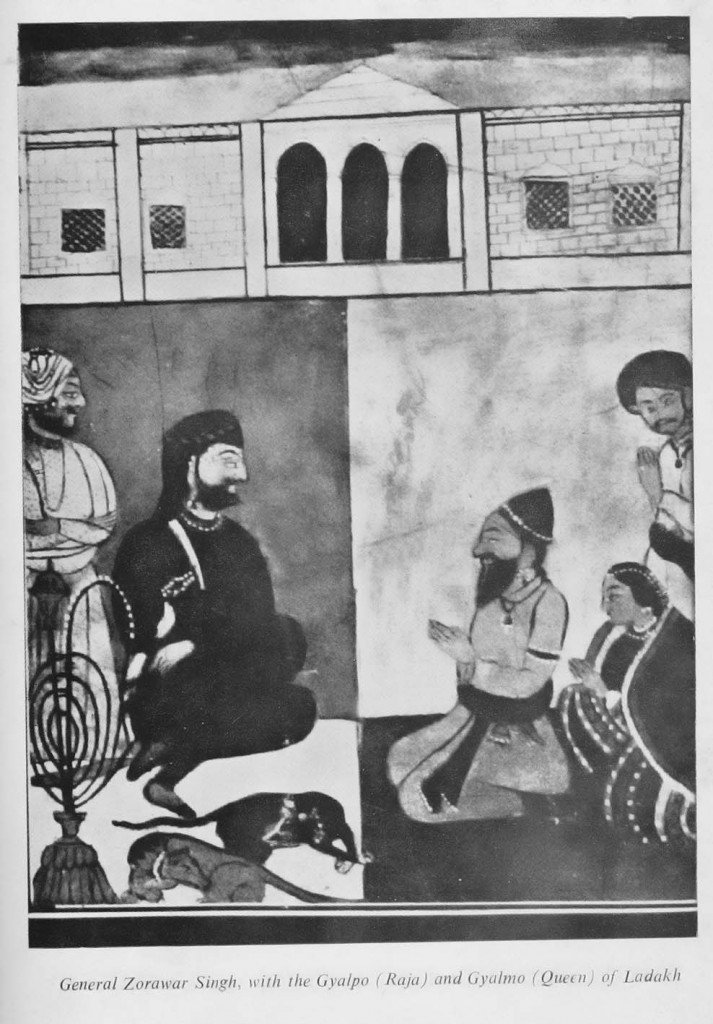

The British had conquered the entire India, falling East of river Sutlej and were now limited by the treaty of Amritsar, signed with Maharajah Ranjit Singh, that stopped them from making a westward advance into Punjab and beyond. It also limited Ranjit Singh from capturing territories east of river Sutlej. The only option for expansion of the Sikh kingdom was North of Kashmir into Ladakh. Zorawar Singh was born at Khalur, now in the state of Himachal Pradesh, which was then a part of Punjab. At a very young age, he rose to become a General in Maharajah Ranjit Singh’s army. In 1834, General Zorawar Singh led an expedition to Ladakh via Kishtwar, Dachin, Marwah, Warwan, crossing the Lanvila pass at 14,500 feet. At Suru and Leh valley, his forces constructed forts for administration of the region.

In October 1835, Zorawar returned to Kishtwar but on hearing reports of rebellion, he immediately turned back and this time took a shorter but more arduous route via Umasila pass at 17,300 feet into Zanskar and Leh, which he reached in ten days. An army crossing at these heights, especially in winter month of November, is one of it’s kind in the annals of world military history. Inclusion of Ladakh in Maharajah Ranjit Singh’s territory is of significant geo-political importance for the present day India. If not for the success of this expedition, with China’s conquest of Tibet in 1950, today it would be a part of China.

Having conquered Baltistan, General Zorawar Singh returned back to Leh via the Khapalu – Chorbat – Nubra valley route. Nubra valley is a high altitude cold desert at 10,000 feet. It is on the historical silk route.

In 1841, General Zorawar Singh turned his attention to the roof of the world, which led him to Western Tibet. Crossing Pangong Tso lake at 14,300 feet, at the Ladakh – Western Tibet border, he travelled via Guge kingdom, Tholing, Purang to Mount Kailash and Mansarovar.

In an operation lasting three and a half months, some 550 miles of Tibetan territory was captured by General Zorawar Singh. In July 1841, GT Lushington, the British Commissioner of Kumaon in India learnt that extensive territories in Tibet have been captured. British were alarmed and decided to send Captain JD Cunningham to the Sikh Darbar in Lahore to discuss the matter as this was seen as a threat to British India. Lahore Darbar remained evasive of Cunnighams queries thus letting General Zorawar Singh have more time to complete his task. By now the winters were fast approaching. General Zorawar Singh decided to move to Tirthapuri and prepare for the offense in the coming summer months.

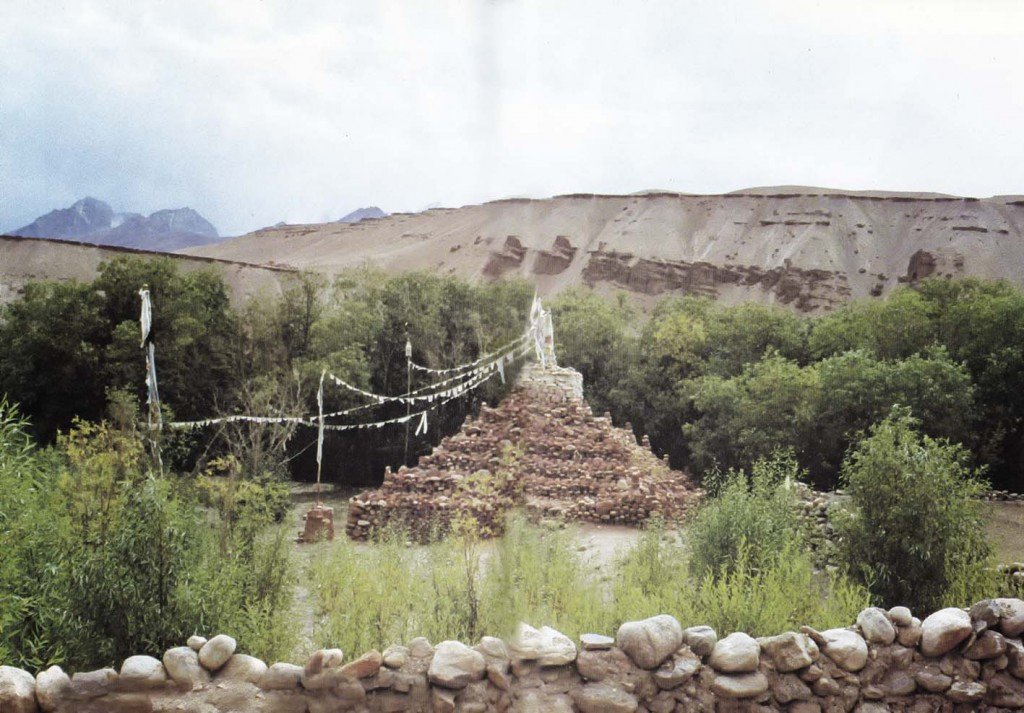

On 12th December, 1841 General Zorawar Singh was hit by a bullet on his left shoulder and died at Taklakot. Even though the morale of the forces was broken, it was only by January 1842 that the last fortifications, under the command of Basti Ram (military officer of General Zorawar Singh) abandoned their positions. With him, many soldiers crossed the Tibetan plateau but only 242 of them reached Askot in Kumaon, which was in the British India territory. From here they continued the journey to Ludhiana and entered the Sikh kingdom to the east of river Sutlej. General Zorawar Singh’s severed head was carried to Lhasa where it was placed at a thoroughfare for public viewing.

About the soldiers who were taken into captivity, Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, who served as Tibet’s Secretary of Finance from 1930 -1950, writes on page 243 – 244 of his book, TIBET – A Political History : “Over three thousand Sikhs were killed in the course of the foray. Seven hundred Sikhs and two Ladakhi ministers were taken prisoners. The remainder of the defeated army fled…. Those prisoners wishing to return to their country were allowed to do so….. One third of the Sikhs and Ladakhi prisoners elected to remain in Tibet. The Sikhs were resettled in warmer regions of Southern Tibet by the government and many married Tibetan girls. The Sikhs are known to have introduced the cultivation of apricots, apples, grapes and peaches into the country.” So what about the skeletons at Roopkund lake? Are these of the retreating soldiers accompanying Basti Ram, who may have lost their way and perished at the high altitude? A recent expedition to Roopkund lake by a National Geographic team retrieved about 30 skeletons and their carbon dating has placed the time of mass death to 9th century AD. The National Geographic documentary can be viewed at this link. Rookpkund National Geographic While the mystery of Roopkund, through scientific investigation has negated it’s linkage to the Tibet expedition of General Zorawar Singh, but a curious conversation with Mr. Vaishnav at The Doon School in the year 1983 has sub-consciously led me to these remote places, tracing the footsteps of General Zorawar Singh. A journey performed over thirty years and I hope to continue to discover more places where the General had once stepped. |