The Penguin Book of Indian Journeys, Edited by Dom Moraes

|

| The Penguin Book of Indian Journeys |

It’s been a couple of years since my wife and I returned from our six-month shoe-string budget backpacking trip (I am very romantic) through India. In every city we visited, from Srinagar in the North to Thiruvananthapuram in the South, we made utterly impractical trips to bookshops, where we bought heaps of books. Then we walked around like overburdened donkeys with our book-laden backpacks while fending off rickshaw-wallas and coolies. And of course we didn’t read any of those books while on the road. Instead, we chatted with people in our rail compartments, drank tonnes of kullar vaali cha, watched black market DVDs on our laptops, and ate lots of delicious, deep-fried and ghee-doused (for good measure) street-food.

Last weekend, on a whim, I started reading a collection of essays called Indian Journeys, a book I had picked up at a tiny bookshop tucked into the Dasaswamedh ghat in Varanasi. And the sole reason I’d picked it up was it had an image of a foot on the cover. The book is not available in the United States, as far as I know, but you can click on this link to read more about it.

I’ve read virtually everything by Salman Rushdie, and while I do find him to be a bit verbose (yes, I just used that word) in describing something trivial, I have an immense amount of respect for the rebelliousness in both the content and style of his writing. At least with Grimus, Midnight’s Children, and The Satanic Verses. He has been very outspoken with his criticism in both his fiction and non-fiction on Indira Gandhi, but have never before come across any of his writing where he even mentions the Sikhs. And yet there it was, in the most random of places, a collection of travel essays. Salman Rushdie’s essay in this collection is entitled “the Riddle of Midnight,” and the overarching theme is the notion of Indian nationality. But what surprised me was learning something about the 1984 Delhi pogroms I had never heard before, or to be perfectly honest, something I had never thought about: the ripping of beards.

Rushdie writes:

| “I heard about many of these deaths, and will let one story stand for all. When the mob came for Hari Singh, a taxi-driver like so many Delhi Sikhs, his son fled into a nearby patch of overgrown waste land. His wife was obliged to watch as the mob literally ripped her husband’s beard off his face. (This beard-ripping ritual was a feature of many of the November killings.) She managed to get hold of the beard, thinking that it was, at least, a part of him that she could keep for herself, and she ran into their house to hide it.” |

|

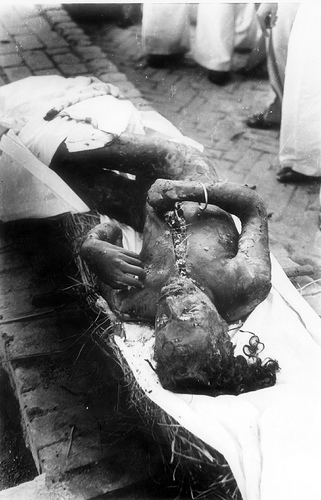

| Sikh victim of the Delhi Pogroms |

I have spent several years researching the events and human stories that lead up to 1984, and very little of the gruesomeness surprises me anymore. It still appalls and horrifies me though. I had heard of the distastefully titled “garland treatment” during the Delhi pogroms, a term used by Zail Singh, the “Sikh” President of India in 1984, in which “rioters” attacked Sikh men and boys, tying their hands together with their turbans, then cutting their hair off, placing a tire around their necks, pouring kerosene over their bodies, and then setting them on fire while their mothers, daughters, wives, and sisters looked helplessly on. I had read about how this particularly horrific form of torture was inflicted upon thousands of Sikh men and boys. I have seen photographs, and even spoke to people who bore witness to these traumatic acts of madness. But I never actually thought about how a single man’s hair was cut off, or his beard removed. With all the gruesomeness of everything else I knew of what had taken place, it hadn’t occurred to me that the beards were being ripped off faces, or hair ripped off heads.

My father, a poet and singer, wrote a very powerful poem showing the historical and religious significance of the Sikh turban, titled “Pag Di Saanjh: A Tribute to the Sikh Turban“ and many Sikh organizations, as well meaning as they all are, place a lot of energy into explaining the turban, and the beard has almost lost its place.

It is in this context that a larger question came to mind, a question that reminded me of a conversation I had with a friend of mine a few days ago. She is very anti-Bollywood because of the industry’s “depiction of Sikhs,” and yet is very aware of all the latest films, which of course she doesn’t watch.

Growing up in a small English town near London, my parents instilled into us that Sikhi was not just something to do over the weekend at the Gurdwara, but a part of our existence, a way of life. We were taught that Sikhi started from the inside and eventually manifested itself in the outward appearance. This outward appearance is something my sister and I took for granted. Most of the Sikh men my parents knew, and some of their sons, wore turbans; some had long flowing beards, while others trimmed their beards. But they had actual beards, not the designer stubble that passes for a beard today.

The anti-Bollywood sentiment is an understandable one, but one that I don’t share. I’ll go ahead and say it. I am a huge fan of old school Bollywood films and some of the newer stuff (none of this modern day gritty film noir rubbish though). And I know many will disagree with my position, but I do not boycott films that have offensive Sikh caricatures like Akshay Kumar’s Singh is King, where the Sikh characters have everything from stubble to goatees, and even Snoop Dogg is sporting a turban like it’s some kind of rock star adornment. I watch these offensive films, taking plenty of notes, and then complain about them on blogs, forums, social media, and I cite plenty of examples. But despite some films like “Singh is King” which many Sikhs I know chant the title of as though it’s something to be proud of, it gives me hope that Bollywood is finally starting to have leading characters who just happen to be Sikh. Rocket Singh, starring Ranbir Kapoor (son of Rishi Kapoor), is one of the few films I liked because it told a clever story with a Sikh lead who a) had a real beard and b) wasn’t relegated to being the jovial, larger-than-life idiot sardar, or a mindless violence-prone gunda. And nobody perpetuates the idiot sardar/violent sardar image in Bollywood better than Punjab de puttar, Sunny and Bobby Deol.

I agree that the Sikh portrayal in Bollywood is far from perfect. But, you have to admit, for making up only 2% of India’s population, we’ve developed quite the reputation, and every leading Bollywood actor today, from Amitabh Bachchan to Akshay Kumar to Salman Khan to Ranbir Kapoor, has played a Sikh. Bollywood is an international obsession, with films being dubbed in languages like Hausa, Mandarin, Arabic, and even Greek. So for 2% of India’s population to positively influence the perception of Sikhs on fourteen million Indians who go to the movies everyday (and that’s just Indians in India. I’m not even counting NRIs, or non-Indians altogether) is nothing to be scoffed at, even if it isn’t perfect. It’s an encouraging start.

|

| From top left: Ranbir Kapoor in "Rocket Singh," Snoop Doggy Dog in "Singh is King," Sukshinder Shinda, and Malkit Singh |

What really troubles me are the turbaned and clearly shaven faces of “Pop” Bhangra: Punjabi “Sikh” superstars with melodic voices like Malkit Singh, Sukshinder Shinda, Gupsy Aujla, the two brothers of RDB, Balwinder Safri (ironically of “Putt Sardaran Da” fame) – and that’s just for starters. Whenever a Bollywood film comes out with a film showing a Sikh character playing the lead, there are countless watchdog groups and general rola-ruppa paun vale upset about the way these characters are portraying Sikhs because they look like . . . .well . . . .”modern” Sikh Punjabi Bhangra singers. Where are those watchdog groups when “Sikh” singers like Sukshinder Shinda and Jazzy B (as spiritual and religious as they may be) wear their turbans, but clearly shave their beards on the cover of a religious album just in time for Vaisakhi? Or when they transition from these religious albums to their regular music videos featuring scantily-clad kudiyan dancing all around them while they’re chilling in the club wearing dark sunglasses?

|

| Nice Turbans. What happened to the dahris? |

I am in no way suggesting that there is such a thing as a “Sikh look,” but I do know there is such a thing as a non-Sikh look and these singers are embodying it. Trimming of the beard is a grey area, and one that many Sikhs engage in today and have for centuries (contrary to popular belief, it was not a creation of British colonialism in India). But outright shaving the beard, or cutting the hair, and still wearing the turban is clearly something else. We place a lot of energy into educating people about the Sikh turban and its place in history, but neglect to think about the actual significance of the beard or the hair under the turban.

It reminds me of a Chinese proverb I read on the back of a box of coriander dumplings I bought in Beijing once: “Han Dan Xue Bu,” which literally translates to “Han Dan learns to walk.” It comes from a story about a man from the State of Yan, who heard that people in the state of Han Dan had a very elegant way of walking. So he went there and studied how the men, women and children walked. But try as he might, he wasn’t able to imitate their way of walking, and in the process forgot how to walk the way he used to, then ended up having to crawl back home.

Perhaps before making sure other people are portraying Sikhs properly, we should make sure we’re portraying ourselves properly? But, on the other hand, we could just sing “la-la-la-la,” do the “Punjabi clap,” and continue boycotting Bollywood in righteous indignation, while stocking up on bhangra tunes.