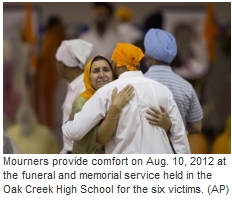

What did I learn in Oak Creek, Wis., responding to a disaster there that left six Sikhs dead in an act of hate? We don’t need signs telling us no blacks or Mexicans (or Sikhs) wanted. Many of us, with the best of intentions, follow the path of segregation subconsciously. And this is disturbingly apparent in our personal relationships.

If you live in a community where the majority of its members are from one race or religion, inevitably you become friends with primarily with members of that race or religion. It is not necessarily something you do deliberately – they are simply there and it is easy. And why bother making an effort to get to know the “other?” Why would a white Protestant real estate broker try to become friends with a Muslim immigrant working the night shift at a gas station?

The massacre in Oak Creek highlights why we need to expand the boundaries of our social circles. The tragedy introduced many Americans to Sikhism and Sikhs for the first time. On the streets, people approached me and my Sikh colleagues, extending heartfelt apologies and sympathies about the shootings against members of the Sikh community. As we thanked these kind people, many also told us that this was their first conversation ever with a Sikh. I also spoke with police officers at Oak Creek, who explained that the general community had no idea who Sikhs were and were wary, until the heinous actions of Wade Michael Page forced the two to interact and discover how much they had in common.

It is sad that the Oak Creek killings were the stimulus to initiate a much-needed dialogue between Sikhs and non-Sikhs. But it is only a start. The segregation in our personal relationships can also trickle into the workplace, where we spend a good amount of our lives and make many of our friendships.

As an employment discrimination attorney, I have worked with Sikh clients who have expressed a sense of isolation in the American workplace. This is especially prevalent among Sikhs who wear a turban and/or maintain unshorn hair (including facial hair) for religious reasons.

Co-workers may argue that it is not personal – it’s just that they doubt they can find common ground with a Sikh, or that an immigrant with an Indian accent is difficult to understand, or that the Sikh colleague is not reaching out to them, either. Perhaps, but it is these stereotypes that may lead the only turbaned Sikh in a workplace to eat lunch alone because he fears he will be taunted for his “smelly” Indian food, referred to as a Taliban or terrorist, and treated differently. Since most of our personal relationships are borne of circumstance, bias-based discrimination can have a devastating psychological effect on our colleagues left out of the water cooler discussion. Of course, the Sikh community also has a responsibility not to remain isolated and must vigorously build personal relationships with our fellow Americans.

Co-workers may argue that it is not personal – it’s just that they doubt they can find common ground with a Sikh, or that an immigrant with an Indian accent is difficult to understand, or that the Sikh colleague is not reaching out to them, either. Perhaps, but it is these stereotypes that may lead the only turbaned Sikh in a workplace to eat lunch alone because he fears he will be taunted for his “smelly” Indian food, referred to as a Taliban or terrorist, and treated differently. Since most of our personal relationships are borne of circumstance, bias-based discrimination can have a devastating psychological effect on our colleagues left out of the water cooler discussion. Of course, the Sikh community also has a responsibility not to remain isolated and must vigorously build personal relationships with our fellow Americans.

Do you know a Sikh? Have you talked to him or her? Do you know a Muslim in your community, a Buddhist, Catholic, a Somali, a Guatemalan, or any individual outside your cultural circle? If so, reach out to them, whether they work in your local deli, coach your spinning class, or read your X-rays. Get to know them and they in turn, will get to know you. Take a Sikh out to lunch. Under the turban, there is likely a person like you with hopes, dreams, family, a love for “Breaking Bad”, “South Park,” yoga, and the “Real Housewives of New Jersey.” By humanizing each other – through friendships - we further marginalize hate and bigotry. This massacre is a wake-up call for us to continue to work to create a more inclusive society – both for our own sake and for each other’s sake.

Gurjot Kaur is a staff attorney at the Sikh Coalition, where she provides legal services to victims of hate crimes, profiling, and workplace discrimination.