He left no photos, no letters, but Sunta Gouger Singh was among 10 Sikh soldiers who fought with Canada in the Great War. And he was the first to give his life.

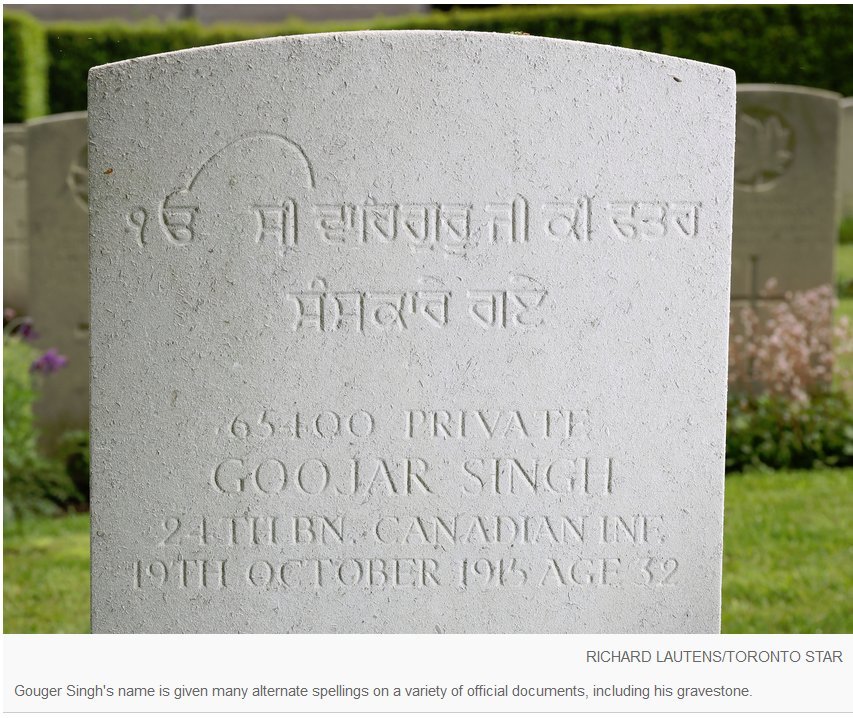

Sat May 03 2014: Kemmel — Sunta Gouger Singh was the first Sikh to die for Canada in the Great War, but his headstone in a rural cemetery outside Ypres is the only Canadian one without a maple leaf engraved on it.

At the outset of the war, most of the men who enlisted were immigrants — most obviously the British who felt a strong tie to the homeland. But there were people from many backgrounds, both new and old to Canada. Among them were 10 Sikhs.

The Sikh population in Canada was small at the outset of WWI, dropping from 5,000 in 1907 to fewer than a couple of thousand by wartime, largely because restrictions, including the head tax, made immigration difficult. Those who were successful usually landed in Vancouver, though many were turned away — most famously, the ship Komagata Maru was denied entry into Vancouver in 1914 because of exclusion laws.

Singh was born in Lahore, Punjab, India, in 1881 and signed up for service in Montreal. On his attestation papers, “complexion” has been crossed out and a word that looks like “caste” is written in its place: “Rugepoot. E. Indian,” which is perhaps a bungled interpretation of a Sikh Rajput.

“The Sikh community has had a long-standing military tradition,” says Pardeep Singh Nagra, the executive director of Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada, noting that photos of early Sikh pioneers in Canada show them wearing military medals. One interesting stat: Sikhs made up 22 per cent of India’s armed forces at the outset of the war although they accounted for less than 2 per cent of the population. Singh had been a member of the Punjab Rifles for three years before he came to Canada.

Gouger Singh's name is given many alternate spellings on a variety of official documents, including his gravestone.

La Laiterie Cemetery is a regimental cemetery; many men buried here were “trench wastage” — a term common in WWI to refer to a soldier killed by a sniper or a shell but not in a major offensive.

Singh’s grave is in the area farthest from the road, under a copse of trees, on the sloping land where the 24th battalion (Victoria Rifles) buried their men.

According to the battalion diary, they finished their tour of nearby trenches on Oct. 4, 1915, with an enemy that was fairly active with “sniping and artillery.” Just beside Singh’s final resting place, headstones marked W.A. Ward, E.A. Clift, mark the human toll of the diary’s neutral language.

On Oct. 13, the men bombarded the enemy’s line and threw smoke bombs. T.G. Smith, buried to Singh’s right, died that day.

On Oct. 16, the battalion was relieved: “Our second tour of duty in the trenches, apart from the bombardment was an uneventful one,” the diary notes. The graveyard and the luxury of hindsight tell another story: six Canadians buried.

While they were resting in billets, working parties were sent to rebuild trenches, day and night. Singh was likely involved in this work; he was killed in action on Oct. 19.

The bureaucracy wasn’t sure how to classify Singh in life or death. On the enlistment papers he belongs to the Church of England, on a death certificate he is Buddhist. At the cemetery, he is listed under “Gougersing” in the registry. His headstone — which spells his name Gougar instead of Gouger — is engraved with Gurmukhi (the most common Punjabi script) that translates as “God is one” and “Victory to God.”

Of the three Sikh Canadian WWI graves, two have maple leafs and one has a cross. Nagra isn’t sure why Singh doesn’t have a maple leaf but believes it might be related to the script, which overlaps the area where the maple leaf usually goes.

There are no photos of Singh, no letters. The museum does have a letter from Sikh Waryam Singh, describing fighting on the Somme in November 1916, where shells and bullets fell like rain and “one’s body trembled to see what was going on.”

“We went over like men walking in a procession at a fair and shouting we seized the trench and took the enemy prisoners. I didn’t think of our safety at all but felt that the Guru Maharaj was fighting in me. He is great and it is thanks to Him that I was able to do all I did … The bravery which we showed that day was the admiration of the British soldiers. After the fight they asked me how it was that I was so utterly regardless of danger,” he wrote.

There is only one name in the visitor book of this cemetery — Mrs. P. Jackson, April 19, 2014, from Carperby North Yorkshire. “Beautifully kept,” she writes.

Leaving the cemetery, the highest peak in Flanders (it is generously called Mount Kemmel, though just 156 metres) was a valued strategic prize in wartime. On the way to the top, past the bunkers where British forces were able to observe nearby Ypres and Messines, a grouse squawks and bursts out of the roadside bramble, the effect a cartoonish explosion.

Up the steep incline is the French ossuary honouring the soldiers who died here in April 1918 when the Germans finally broke through.

At a nearby hotel, we are given a room with a view. The man at the front desk says he’d do the same for anyone, from any country. Maybe not Germany, he says, smiling. They did take this place twice.

And as photographer Richard Lauten chimes in, on those occasions they didn’t make a reservation.