| Sikh Apparel Over Time

From Chinar Kameez to Denim Jeans: The Transformation of Apparel in the Family Archive |

|

July 8, 2015: I remember being very young and always curiously venturing into the living room of my childhood home, propping myself onto the sofa, and taking out stacks and stacks of old photo albums. I never quite knew what the allure of these photographs was: perhaps it was the South Asian nostalgia, the faded quality of the photograph itself, or the sweetness and humility that emerged from every face I lay my eyes on. I was constantly opening and re-opening the albums, taking out the photos to gaze at them more intensely, putting them back, and repeating the process. As I got older, I focused on the images that emphasized the diasporic experience of my family. I was fixated on the ones that depicted their daily lives in Southwestern Ontario, which were starkly different from those that showed them in the mountains of Kashmir and Punjab’s plains. Whether it was scenes of a picnic at Niagara Falls, showing a group of family members sitting on the grass, surrounded by Caucasians in the background and pots of Indian food on decorative Kashmiri blankets, or two men with beards and turbans posing proudly in front of a gas station, it was this fine balance between the Southwestern Ontario backdrops juxtaposed with immigrant brown bodies which haunted me.

It wasn’t until many years later, upon the completion of my undergraduate studies that I began to ruminate once more on these images, when I stumbled upon an old book in my childhood home. The book, Sikhs in Ontario (out of print since 1993) quickly became the perfect entry point for me to learn more about the history of Punjabi Sikh communities amid the South Asian diaspora in Canada. It was in this book that I read Hugh Johnson’s essay Sikhs in Canada, in which he beautifully crafted the story of immigration and assimilation of these early pioneers at the turn of the 20th century. When I read the story of Mrs. Dhan Kaur Johl, one of the first Indo-Canadian women to come to Canada, I was left speechless at the way Johnson resurrected her experiences, luring the reader into the harsh realities that South Asian pioneers faced in the aftermath of immigration. Mrs. Johl talks about being forced to wear Western clothes and the devastation she felt when her brother-in-law took all of her Punjabi suits and burned them in the stove, one by one. In Becoming Canadians by Sarjeet Singh Jagpal (out of print since 1994) I learned the story of another Indo-Canadian woman, Mrs Paritam Kaur Sangha, who recalled, Screen Shot 2015-07-08 at 10.47.08 AM

These horrific stories never left me, and I continued to realize the psychological impact and pressures white supremacy placed on South Asian men and women in Canada who were forced to fit into a hostile, racist Western society. Whether it was the racial taunts and slurs that men faced for sporting turbans and beards, or the burning of Mrs. Johl’s Punjabi suits, or the way Mrs. Sangha was dragged into the clothing store (that was doubly loaded with patriarchy) it was these small little anecdotes lost in history and only subtly resurrected in publications long out of print, which has allowed me to re-examine the transformation of my family’s apparel in a whole new light. I began to re-enter the family archive, staring at the photographs of my family in the diaspora through a completely altered lens. The isolation, loneliness, and a sense of communities being rendered invisible made me look at the ways in which these feelings existed not just in the story of Canadian South Asian pioneers but also in the archives of my own family photographs as well. I started to curiously probe my own mom’s abrupt shifting of clothing in a whole new manner. She told me that the western attire she adorned illustrated the choices she wanted to make regarding integration and identity, echoed by the assimilation around her. These choices have not just limited themselves to the story of women like Mrs, Pritam Kaur Sangha or Mrs. Dhan Kaur Johl at the first half of the 20th century, but have emerged again and again throughout history. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes that photographs are structured by a dialectic tension between the studium and the punctum. The studium, he states, reveals the banal nature of the photograph. The punctum however is a moment in the photograph that disrupts the studium, forcing the viewer to have feelings of apprehension or loss. I now look at old photographs of Indo-Canadian men and women in public archives at the turn of the century and my family archive photos cautiously aware of their punctums, ominously present through the transformation of their apparel.

|

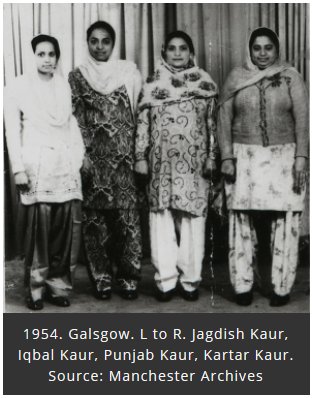

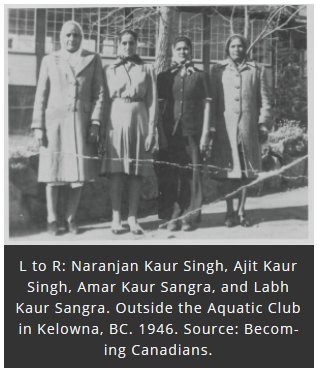

One of the things that compelled me most about the photographs was how my family members’ apparel transformed over time. The early photographs showed women first arriving in the Americas sporting Punjabi dupatta suits in one photograph and a Kashmiri chinar kameez in another, their eyes twinkling with the excitement of being in a foreign land and imagining the vast opportunities that Canadian soil must have for them. A few years later, the photos showed these same women in denim jeans, skirts, and dresses as if they had been violently stripped of the traditional Kashmiri Punjabi garb they arrived in.

One of the things that compelled me most about the photographs was how my family members’ apparel transformed over time. The early photographs showed women first arriving in the Americas sporting Punjabi dupatta suits in one photograph and a Kashmiri chinar kameez in another, their eyes twinkling with the excitement of being in a foreign land and imagining the vast opportunities that Canadian soil must have for them. A few years later, the photos showed these same women in denim jeans, skirts, and dresses as if they had been violently stripped of the traditional Kashmiri Punjabi garb they arrived in. “On the day I arrived in 1932… my husband took me to the shop to get new clothes right away. I pleaded with him that I hadn’t had anything to eat and that I was starving but he did not listen. First, we got the new dresses and later we got something to eat. It was the rule then to dress like the white ladies and keep our hair covered with a scarf at all times.”

“On the day I arrived in 1932… my husband took me to the shop to get new clothes right away. I pleaded with him that I hadn’t had anything to eat and that I was starving but he did not listen. First, we got the new dresses and later we got something to eat. It was the rule then to dress like the white ladies and keep our hair covered with a scarf at all times.” The 21st century has seen, if one ventures into the neighborhoods of Southall, Brampton, and Surrey (towns on the periphery of Toronto, Vancouver and London England) a large, thriving South Asian community. These towns, along with many other towns throughout England and the Americas where a South Asian diaspora is present, show the ways in which apparel has been transformed once again, with many South Asians now adorning their Punjabi garb proudly on the streets and not just having these clothes be confined in the domestic, safe spaces of their homes or the local Gurdwara. Perhaps this is due to the overt decrease in racist western attitudes and rooted ideologies, but there has been a greater sense of resistance to Anglicized culture that has emerged. However, one must never look at these communities with just a sense of resilience seen through the wearing of traditional juxtaposed with western apparel and forget the sacrifices that the pioneers of these communities endured. These feelings of marginality and discrimination continue to linger today, but a sense of hope and optimism to fighting white supremacy is now stronger then ever. It is through an intensive examination of the apparel in these photographs that has forever changed my own perception on just how deep the psychological impacts of immigration into a western society is and continues to be.

The 21st century has seen, if one ventures into the neighborhoods of Southall, Brampton, and Surrey (towns on the periphery of Toronto, Vancouver and London England) a large, thriving South Asian community. These towns, along with many other towns throughout England and the Americas where a South Asian diaspora is present, show the ways in which apparel has been transformed once again, with many South Asians now adorning their Punjabi garb proudly on the streets and not just having these clothes be confined in the domestic, safe spaces of their homes or the local Gurdwara. Perhaps this is due to the overt decrease in racist western attitudes and rooted ideologies, but there has been a greater sense of resistance to Anglicized culture that has emerged. However, one must never look at these communities with just a sense of resilience seen through the wearing of traditional juxtaposed with western apparel and forget the sacrifices that the pioneers of these communities endured. These feelings of marginality and discrimination continue to linger today, but a sense of hope and optimism to fighting white supremacy is now stronger then ever. It is through an intensive examination of the apparel in these photographs that has forever changed my own perception on just how deep the psychological impacts of immigration into a western society is and continues to be.