"Naanak Satheeaa Jaaneeanih J Birehae Chott Marannih"

Celebrating the Resolve Of Survivors & Humanity Of Those Who Helped

INTRODUCTORY

Next year, 2013, will usher in the 30th anniversary year of the November 1984 killings of thousands of Sikhs, mostly in the Capital city of Delhi right under the nose of the Central Government and the Delhi Administration. The orgy of violence and the manner of its execution will likely remain unparalleled as perhaps one of the most ruthless and deliberate selective killing of a minority group instigated by the ruling political elite of a country in the recent human history.

A summary review of the event and its aftermath point to some developments in the recent years that go part of the way to assuage the Sikh hurt but the expectations about delivery of justice have mostly been belied. This has brought the situation to an almost static position that is not quite easy to read or predict the future. The purpose of these Articles is to explore if while the judicial and other processes wind their way through the various systems, there is any other option that may help alleviate some of the continuing hurt and improve the lay sentiment. The option considered is memorializing as a way to honor those who might have contributed to helping the distressed, blunting the momentum of violence, struggling to seek justice, helping transcend the urges for revenge and save the next generation from bitterness and apathy, and thus, through their acts promoted some level of societal peace and harmony.

A summary review of the event and its aftermath point to some developments in the recent years that go part of the way to assuage the Sikh hurt but the expectations about delivery of justice have mostly been belied. This has brought the situation to an almost static position that is not quite easy to read or predict the future. The purpose of these Articles is to explore if while the judicial and other processes wind their way through the various systems, there is any other option that may help alleviate some of the continuing hurt and improve the lay sentiment. The option considered is memorializing as a way to honor those who might have contributed to helping the distressed, blunting the momentum of violence, struggling to seek justice, helping transcend the urges for revenge and save the next generation from bitterness and apathy, and thus, through their acts promoted some level of societal peace and harmony.

THE EVENT

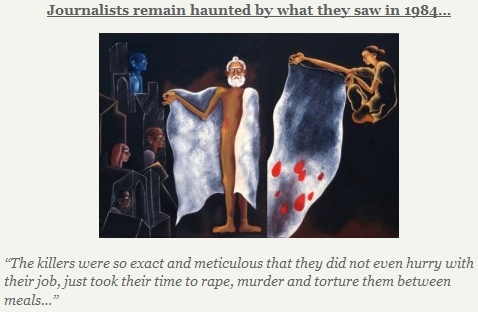

The event was a politically inspired pogrom let loose on Sikh men, women and children in Delhi after the killing in 1984, of Indira Gandhi by two of her Sikh security guards piqued by the Indian army's assault to clear militants holed up in the Golden Temple complex. Three days of organized mayhem followed in the Indian Capital in which over 3000 Sikhs were killed mercilessly, many with their families helplessly looking on, while Police idly stood by.

Sikhs recall 1984 as the most traumatic year in their recent history. In June, on the day their fifth Guru was martyred, the Indian Army attacked the Golden Temple complex at Amritsar, using helicopters and tanks, to flush out militants holed up in the Temple complex. This was preceded by a sustained media blitz to paint the entire Sikh community as secessionists and unpatriotic militants.

Gurdwaras in various colonies were vandalized or torched.1 All Sikhs felt insecure - none was safe. In most localities Sikh houses and businesses were marked so that these could be easily identified and selectively attacked by the hoodlums. Mostly the attackers were from outside the localities though in some cases some local elements joined in. Victims identified some of them and a list of individuals is included in the report entitled 'Who are the Guilty'. It names around 200 persons including a number of politicians, police personnel and Muslims - all of them known persons. The manner of killing of Sikhs seemed to have been fairly consistent in that the victims were burnt alive by putting a tire around their necks, sprinkling kerosene mixed with a white powder, believed to be phosphorous, and lighting it with a match stick. In all this mayhem the killing was mostly carried out in some localities - it was avoided where the local people of good will came together or by timely intervention by volunteer groups and in a couple of cases where the Sikhs under attack were armed and able to offer resistance.

Sikhs in India and particularly in Delhi felt insecure for a long while following this pogrom. Delhi Sikhs recall that they did not use loud speakers in Gurdwaras or took out early morning prabhat pheris at festival times for several years.2 Many families migrated to the safety of Punjab or to foreign lands, if they could find a way to do it. A number of families that had left the more affected localities in Delhi did not return to their houses in those areas. Sikhs mostly avoided market areas, railway stations, airports, cinemas and other public places, during evening hours. Many parents decided to get the hair of their sons cut in order to avoid bullying and risk to their lives. Sikhs were targeted for special checks by security personnel, often in rough and intrusive manners.

THE MISLEADING SEMANTIC TWIST

The political establishment and the state controlled media labeled the event as an anti Sikh riot implying it to be a spontaneous violent outburst against Sikhs arising out of mass anger at their co-religionists killing Indira Gandhi. It was also openly talked that Sikhs deserved 'to be taught a lesson' because of the violence Sikh militants had committed against Hindus in Punjab. Rajiv Gandhi seemed to be echoing the same line of reasoning when he matter-of-factly said that 'Some riots took place in the country following the murder of Indiraji. We know the people were very angry and for a few days it seemed that India had been shaken. But, when a mighty tree falls, it is only natural that the earth around it does shake a little.' The media were very pliant and did their bit to play up the disturbed conditions in Punjab and widely used the press releases by the Government controlled sources regarding the Delhi happenings. Misra Commission almost took the cake in underplaying the event as a law and order problem with lower castes looting the wealthy with the complicity of police-criminals-politicians nexus.

Human rights organizations People's Union for Civil Liberties [PUCL] and the People's Union for Democratic Rights [PUDR] however opined that 'far from being spontaneous expressions of madness and grief and anger at Mrs. Gandhi's assassination as made out by authorities, [it] was rather the outcome of a well organized action marked by acts of both commissions and omissions on the part of important politicians of the Congress (I) at the top and by authorities in the administration.'3 Citizens for Democracy stated that the purpose was 'to arouse - Hindu chauvinism - to consolidate Hindu votes in the election held on December 27, 1984, which was indeed massively won by the Congress (I).'

Report of the Citizen's Commission observed 'The disturbances in Delhi did not involve clashes between any two warring factions, each inflicting whatever damage it could on the other. They were entirely one sided attacks on members of the Sikh community and their property, often accompanied by arson and murder, rapine and loot. In some localities the outrages amounted to a massacre of innocent persons.4' Commenting on the role of political parties the Citizen's Commission said 'eye witness accounts to the Commission have specifically and repeatedly named certain political leaders belonging to the ruling party --- accused of having instigated the violence, making arrangements for the supply of kerosene and other inflammable material and of identifying houses of Sikhs ---- We have been equally disturbed by the apathy and ambivalence of other political parties --- It is a sad commentary on the political life of the Capital that at the moment of its direst need, political activists should be accused of either active instigation or inexcusable apathy.'5

It therefore would seem only reasonable that the notion of the event being a communal riot or an expression of mass societal anger against the Sikhs must be rejected. The evidence leaves no doubt that the violence was meticulously planned, well coordinated, directed specifically at Sikh males and executed in almost identical manner in all localities. Given this, the most lenient term that may be used to label it would be a 'pogrom' - an organized and officially encouraged massacre of a minority group - of Sikhs in locations where they were vulnerable.

A PEEP AT THE BACKGROUND Sikhs as a community and the Indian Central Government, led mostly by the Congress Party since the Country's independence on 15 August 1947, had a certain sub-text of tension in their relations. Sikhs nursed a sense of being victims of and the biggest losers due to partition of the Country. They not only had suffered the highest loss of life and property but they were also separated from some of the most sacred of their holy sites left in Pakistan due to the endemically adverse relations between the two Governments. Another source of Sikh anguish was their failure, during the protracted negotiations preceding the Partition, to secure any tangible gain or assurance about their future in the divided Dominions.

Having cast their lot with India and the Hindus, Sikhs soon started feeling that policies of the Central Government were not likely to answer their expectations. Article 25 of Constitution adopted in 1950 put Sikhs within the Hindu pantheon. In 1956 when most of the Indian States were reorganized on linguistic basis, Punjab was left as is because of the Punjabi Hindus disowning Punjabi as their tongue. After persistent agitations, a Punjabi state was ceded in 1966 but the division left many unresolved issues including non-inclusion of Chandigarh as its Capital town. In a climate of increasing polarization, Anandpur Sahib Resolution passed by the Shiromani Akali Dal sought a federal structure at the center with more devolution of powers to states, increase in the pace of industrial development, share of river waters and Chandigarh as the exclusive capital of Punjab along with some other minor demands. The Central Government responded by characterizing the Resolution as secessionist and went all out to stigmatize Sikhs as anti national in the state controlled media.

The ensuing tense political climate offered the opportunity for Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the head of powerful Sikh Seminary, Damdami Taksal, to tap into the Sikh discontent. He supported implementation of the Anandpur Sahib Resolution and strongly condemned the Article 25 of Indian constitution. The preacher in him challenged Sikhs to pull back from the path of declining Sikhi practices. His fiery speech and rhetoric of defiance marginalized the influence of political leaders as well as the Government that allowed different interest groups to manipulate the climate of unrest into a wave of killings of civilians as well as police. This was attributed by the Indian government to Sikh militants. In a fast deteriorating environment Bhindranwale moved into the Golden Temple Complex in 1982. Allegedly planted at the behest of Giani Zail Singh to weaken the SAD, Bhindrawale now had become a challenge for Indira Gandhi who ordered the Indian Army to attack the Golden Temple Complex to capture or neutralize him.

The assault made on June 6, 1984, the martyrdom day of Guru Arjan when the complex was filled with pilgrims, caused destruction of the Akal Takht, killing of Bhindranwale and his main associates as well as an unspecified number of Sikh worshippers and Gurdwara Clerics.

Sikhs the world over were shocked by the attack on their most sacred Gurdwara and outraged by the concerted media campaign to paint the community in bad light to justify the offensive by the Army. The killing of Indira Gandhi by her two Sikh bodyguards on October 31, 1984, ostensibly piqued at her ordering the army attack on the Golden Temple was tragic but not unexpected. It however was used to set off a second sequence of mass violence, this time in Delhi, the capital of India. It lasted for four days and resulted in death of nearly 3,000 Sikhs. That is the event and its aftermath that we are reminiscing about.

WHO WAS THE OFFENDER?

There is broad agreement among analysts that the pogrom was instigated by the Congress [I] politicians helped in its execution by Delhi police and a section of Hindus. Van Dike [1996] is of the view that the passive stance of Central Government indicates that the pogrom was organized for it by forces that government had created. Looking at the scale of violence that was unleashed in such a short time, Kothari [1985] speculates that the attack might have been planned possibly since Operation Blue Star. Brass [2006] suspects that an institutional riot structure had been readied to be available in Delhi.

That spontaneity is ruled out is supported by credible evidence collected by a number of voluntary agencies pointing to the conclusion that it was Congress [I] leaders who gathered the perpetrators, led the mobs, distributed weapons and identified targets. Prominent names mentioned as instigators in the affidavits filed by the witnesses are Dharam Dass Shastri, Jagdish Tytler, H.K.L Bhagat, Sajjan Kumar and Kamal Nath.

Given the sullen mood of Sikhs post Blue Star, the killing of Indira Gandhi could not have been ruled out and when it did happen, the response that was orchestrated bore the stamp of meticulous planning, with the pogrom as its centre piece. The message was clear: Blood shall flow as recompense for blood. Sikhs are separatists and a danger to the unity of India and must be taught a lesson.

The attacks everywhere started simultaneously and Gurdwaras were the first targets. Modus operandi was to grab and pull Sikh men out, tear off their turbans, beat them with iron nods or knives, neck-lace them with a tire and set it on fire [Grewal, 2007]. Women and children were spared though some women were killed and many gang-raped, often in front of their relatives. The properties were looted and set on fire. The Congress leaders were assisted by gang leaders from the resettlement colonies that had been set up to relocate slum dwellers during the Emergency. Some Jats, Gujjars and Bhangis also participated in looting the well-off Sikhs.

The Delhi police was conspicuous by absence or if there, in encouraging and even indulging in violence. The police disarmed Sikhs who tried to protect themselves by force and did not record FIRs after the pogrom. Nanavati Commission noted that there was ample material to show that no proper investigation was done by the police even in cases which were registered by them. Police vans went around announcing that Sikhs had poisoned the city water supply and that a train had arrived from Punjab full of dead Hindus. Active acts of rumor mongering by Police only aggravated the situation.6

The title of the first citizen group enquiry into the pogrom soon after its occurrence by Justice Sikri and his volunteer team was 'who is guilty?' This enquiry clearly holds the Government agencies, the Police and Congress Party political leaders as the guilty.

WHO WAS THE VICTIM?

Let us recall that the pogrom did not target any specific Sikh activists or community leaders who may have had something to do with causing the sense of disaffection to grow among the lay Sikhs and thus could have been the object of ire of the authorities in the same manner as some specific persons have been targeted by the Israelis in Palestine and Americans in Iraq or Af-Pak region in the course of recent and ongoing conflicts there. The target was the Sikh community and the objective was to teach them a lesson - an abridged version of the doctrine of 'Shock and Awe'7 that determined the American strategy at the start of their War Against Terror and that draws on experiences of massive, benumbing destruction like at Hiroshima and Nagasaki intended to break the will of those identified as enemy.

A recognition that often eludes even well meaning and thinking Sikhs is their inability to see through the risks that such policy would entail even for Sikhs who may have been opposed to the approach that the militants among them had chosen. The fact is that even if persons like Dr Manmohan Singh who had been staunch Congressites all along had been seen walking the streets by the marauders they would have had no hesitation in hacking him to pieces as they did to other Sikhs. Thus those who actually suffered harm were not specifically picked targets - any other Sikh would have equally merited being the target just for being a Sikh.

In October 1984, 500,000 Sikhs made up 7.5% of Delhi population. The victims were mainly Sikh males in the 20-50 age group. Women were spared though some suffered violence, mainly rape showing the incapacity of Sikh males to protect their women. The official death toll was 2,733, leaving over 1,300 widows and 4,000 orphans [Kaur, 2006]. Besides, more than 50,000 Sikhs left Delhi after the pogrom. The worst affected were the poor Sikhs in the resettlement colonies who had actually been close supporters of Congress - the middle class neighborhoods saw more looting than killing. The survivors, mainly widows, orphans and old people, went to relief camps, Gurudwaras and relatives' houses.

Interestingly when we talk of victims our thoughts always go to those directly affected by the pogrom and suffered loss of life and property. The face of victims is the group of widows that survived their husbands and were burdened with responsibilities for their families. They form the core of victims but do not constitute the totality of them. This realization is important not because it fits into the shared Sikh hurt but also because the character of the pogrom was more akin to genocide even though the Commissions of Enquiry have been more about seeking simple justice for those killed, compensation issues for their families etc. If the identity of victims is recognized at two levels i.e. at the level of community as Sikhs without reference to their affiliation or location and as those whose near and dear ones came in the way of harm, it would help us in better understanding of the complexities this community wide spread of those who feel aggrieved about the pogrom adds to the resolution of issues.

SOME BITS OF AFTERMATH & MY SEARCH

In the immediate aftermath of the November pogrom while the Government seemed implicit in the killings, media stood silent and the Nation apathetic, it was some groups of concerned citizens across the religious boundaries who took the courage to launch initial relief efforts and independent investigations into what had transpired. The Government appointed a Commission of Enquiry, followed by other commissions and till to-date in spite of several Commissions of Enquiry and investigations by the CBI neither has justice been delivered nor are the Sikhs closer to any sense of closure to the traumatic event.

No doubt the long and laborious process of helping the widows and thousands of kids to cope with their loss and get on with life was the most important humanitarian task. After the initial help of interfaith groups, mostly the Sikh communities, Sikh volunteer groups and Gurdwaras undertook this onerous and long term commitment. The stories of those directly affected are a testimony of the resolve of the widows who drew on their inner strength and religious beliefs while trying desperately to raise the kids to be able to cope with a world that could not have been crueler.

They succeeded only partly - many kids could not cope - they became school drop outs, took to drugs, some committed suicide. Some widows also resorted to suicide to end their misery. While still struggling with their grief and grinding poverty, the widows have grown into old and tired women and the children have grown into men and women still living in poverty and consciously aware of their grief and grievances. In spite of almost three decades of suffering, no one from among the victims' families is known to have indulged in any act of revenge, rioting, violent crime, hate incident, terrorism or any other socially disruptive or anti social behavior. That it happened is a fact. That it happened in a world that continues to revel in tit for tat, eye for an eye kind of spiraling hate crimes and terrorist acts is also true.

How did it come about? What happened? Could there be something to learn here for the rest of the deeply divided world consumed by un-diminishing passion for revenge and hate? My initial search was driven by questions as above with a view to understand this unrecognized and unexplored fallout from a gruesome happening. I also was curious to find out how some Sikh pockets had survived during those days in villages from where some of the hoodlums could have been recruited by the organizers of the pogrom.

In this pursuit, I spent time with the leadership and activists engaged with Nishkam and the Sikh Forum who had a wealth of information and were willing to share it. Nishkam had been involved with the relief and resettlement of the victim families from the beginning and many of the widows were still in almost day to day contact with them. They were helpful in organizing meetings with several members of victim families and a full day town hall type interaction with a group of widows and two of the kids, now grown men.

Nishkam also facilitated a visit for me to four/five Sikligar sites in Western UP along with the Chairman of Meerut based Mata Gujri Seva Society who were actively engaged with these communities. These villages possibly were the type of communities from where the ring leaders of the pogrom had been able to muster the men to form their marauding gangs. The Sikligar populations in these communities were left untouched possibly because the dominant Tyagi zamindars and Sikligars had a relationship built on mutuality of respective needs - Sikligars needed place to live and the zamindars needed their muscle to control their interests.

As I proceeded with my search, I found in my conversations with the widows that neither had they forgotten nor did they want their children to forget what had happened to them. So while they wanted the memories to survive they did not want their children to be consumed by hate, animosity or a burning impulse for revenge but instead to learn to live with their trauma and remake their lives. They were deeply resentful that neither had any of the prominent organizer s been found guilty nor had they received the compensatory help that they had been promised from time to time by the Government. Peaceful response by them therefore was a deliberate choice, not the result of amends being made by the organizers of the pogrom. The Sikh community seemed to have moved on by putting the problem on the back burner - not forgotten but not just now - kind of attitude.

This led me to attempt an analysis of factors that were complicating this issue and inhibiting its moving out of its static posture. The discussion in the papers that follow is intended for us to look at the various imperatives, initiatives and options that often come to our minds when we think of this event and try finding a comprehensive way forward that may be in harmony with the Sikh aspirations and Sikh ethos of societal peace and harmony.

-

Nirmal Singh,

New Cumberland, PA

---------------------------------------

Notes:

1 - The orgy was not confined to Delhi. Sikhs and their Gurdwaras were targeted in several places in the country. One of the Gurdwaras demolished was 450-year-old gurdwara Gyan Godhri set up at Har-ki-Pauri in memory of Guru Nanak who visited the place in 1504-05. The Sikh community of Uttarakhand has been demanding that the shrine, which was demolished during 1984 anti-Sikh riots, should be restored at its original place. SGPC is now pursuing the matter with the state Government [16/9/12].

2 - Verbal testimony by some of the speakers and participating Sikhs at a memorial meeting organized by the Sikh Forum on 2 June, 2012 at IIC Annexe New Delhi.

3 - Who Are Guilty? Report of a Joint Enquiry into the Causes & Impact of the Riots in Delhi from 31 October to 10 November, PUDR-PUCL, 1984

4 - Report of the Citizen's Commission, !8 Jan, 1985, p. 38

5 - Ibid, p. 32

6 - This summary is based on a large number of books, and articles including the books, reports, web resources etc. variously mentioned in the text of this paper.

7 - Shock and Awe is a military doctrine based on the use of overwhelming power, dominance over awareness and spectacular display of force to paralyze the adversary and destroy its will. Written by Harlan K. Ullman and James P. Wade in 1996, it is a product of the National Defense University of the United States.