|

| The lawyers Parijata Bharadwaj, left rear in a black scarf, and Guneet Kaur, center rear, talking to villagers about police violence. Credit Kuni Takahashi for The New York Times |

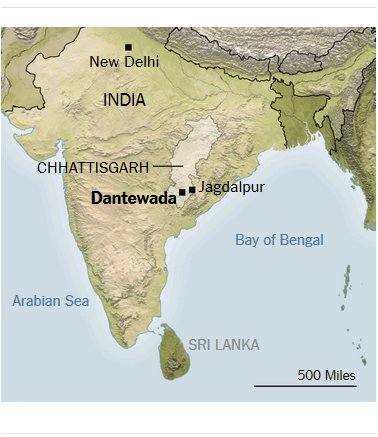

March 1, 2015: JAGDALPUR, India — On a quiet night last November, the human rights lawyer Shalini Gera was brewing tea in her drab, small-town office, which doubles as an apartment, when her basic Nokia phone began vibrating on a plastic table.

The call came from an informer in a remote village, several hours from her home in Jagdalpur, a dusty market town surrounded by forests that for the last decade has been the main theater of India’s war against Maoist guerrillas known as Naxalites, named after the town Naxalbari, where the guerrilla movement formed in the 1970s.

The local police had surrounded the village, aiming to coax out a man suspected of being a militant. When he did not emerge, the police instead arrested 26 bystanders and charged them with digging up part of a nearby highway, ostensibly part of a Maoist-led sabotage campaign. The caller warned Ms. Gera that the police had beaten many, some badly, before forcing them to confess.

Ms. Gera, 44, told her caller that she and her colleagues would travel to the village as soon as possible, though their operation is so bare-bones that they can afford to travel only by infrequent public buses. As usual, there was no hint of panic in her voice.

“We’ll only be able to prove that the police have beaten these people if we get these things called medical legal complaints made,” Ms. Gera said after ending the call.

“We’ll only be able to prove that the police have beaten these people if we get these things called medical legal complaints made,” Ms. Gera said after ending the call.

“Normally, that doesn’t happen.” Medical legal complaints are doctor-attested documents that let lawyers in India lodge legal complaints against the police for brutality toward those in their custody.

Ms. Gera likes to joke that, until recently, the closest she got to rural life was in San Jose, Calif. But here in Jagdalpur, in the central state of Chhattisgarh, she has become intimately familiar with the rhythms of a deeply troubled countryside — and the legal travails of the region’s indigenous people, known as adivasis.

Five years ago, she was a consultant in the Bay Area pharmaceutical industry, and a homesick member of the large Indian diaspora there. But on trips back to India, she became more and more passionate about social justice. Sudha Bharadwaj, a firebrand trade unionist and lawyer working mostly with laborers in steel plants and mines, urged her to look at Chhattisgarh, where human rights abuses are often overlooked in the clamor of a long-running conflict.

“What we really need here, more than anything else, are good lawyers,” Ms. Bharadwaj told her at the time.

Sick of engaging from the sidelines, Ms. Gera abandoned two decades of climbing the American academic and professional ladder, and set off on a drastic career change.

In 2010, Ms. Gera enrolled in Delhi University’s law program. There, she met Isha Khandelwal, 24, who also had redirected her trajectory from studying computer programming to studying human rights law in the capital. Together, and with the help of Ms. Bharadwaj, they founded a private legal aid group, operating on a shoestring budget comprising scholarships, donations, and personal savings.

Legal aid for adivasis is hard to come by. Article 39a in India’s Constitution mandates free legal representation for a huge percentage of the population. Still, more than two-thirds of inmates in Indian prisons — more than 265,000 people — are awaiting trial, according to the latest figures from the National Crimes Records Bureau. The situation is still more dire for the mostly adivasi defendants of southern Chhattisgarh, where both the Naxalites and the state’s armed forces have been accused of countless extrajudicial killings and the razing of entire villages, contributing to an entrenched security mentality.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Ms. Gera said. “We’re not saying that Naxalite attacks don’t happen. But when it comes down to it, most of these cases are completely baseless.”

In July 2013, Ms. Gera and Ms. Khandelwal, together with another recent graduate, Parijata Bharadwaj, 25, who is no relation to Sudha, moved to Jagdalpur and founded the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group, leaving behind fretful friends and families in cities far removed from the conflict. A year and a half later, the three are now four — joined by Guneet Kaur, 24, a recent law degree graduate from the University of California at Berkeley. The team of young lawyers is now known by a nickname reminiscent of a made-for-TV drama: JagLAG.

They live together, sharing spartan quarters in the office-cum-apartment. Mealtime conversations revolve around the dozens of cases they are juggling. There are no weekends, and trips home are few and far between.

Ms. Gera goes almost every week to the district court in a nearby town called Dantewada. On a recent morning, in an empty hallway of the court, she took a black sports coat out of her backpack, unfolded it, put it on, and affixed a white advocate’s collar around her neck. In a country where court complexes are ordinarily filled with commotion, this one was a scene of relative serenity. Barely a handful of people milled about. Lawyers and judges sat on plastic chairs in the courtyard, sipping tea in the winter sun.

Ms. Gera goes almost every week to the district court in a nearby town called Dantewada. On a recent morning, in an empty hallway of the court, she took a black sports coat out of her backpack, unfolded it, put it on, and affixed a white advocate’s collar around her neck. In a country where court complexes are ordinarily filled with commotion, this one was a scene of relative serenity. Barely a handful of people milled about. Lawyers and judges sat on plastic chairs in the courtyard, sipping tea in the winter sun.

It is not that there are not cases to process — in fact, hundreds of cases are pending in Dantewada. According to government statistics on jails in Chhattisgarh, only three out of the 600 or so inmates in Dantewada’s prison are convicts. The rest await trial in a jail that was only built for a capacity of 150, sleeping in shifts for lack of floor space.

Most of the accused are poor and adivasi, and more than three-quarters of the cases deal with grave crimes such as murder. Charge sheets are filled with insinuations that the accused are tied to Naxalite factions, and bail is rarely granted because the accused are seen as national security threats.

The swell of so-called “undertrials” does not reflect an increase in arrests but an achingly slow judicial process. The rate of arrests in the region is roughly the same as in the rest of India, but only 10 percent of cases in Dantewada are wrapped up within a year, and more than 40 percent take more than two years to conclude, Ms. Gera and her colleagues found when they reviewed court documents.

It was while poring over those documents that JagLAG discovered the cases of Midiyam Lachu and Punem Bhima, who had spent six and a half years in an overcrowded jail awaiting trial. The four women were the first to discover that neither Mr. Lachu nor Mr. Bhima’s names appear even once on the charge sheet pertaining to the attack in which they stand accused. The lawyers surmise that neither the judge nor the men’s previous legal aid lawyer had ever bothered to read the charge sheet. After pointing out the oversight, JagLAG procured bail for them last year, though the judge has declined to drop the case entirely.

Sudha Bharadwaj, who mentored the JagLAG lawyers, said she believed that the authorities used stalling tactics to sideline people they thought were potential Naxalites. “The police, in collusion with the courts, are draining the water to kill the fish,” she said. “The state is conflating adivasis with Naxalites.”

When Naxalite attacks do happen, an already hostile environment gets more hostile. Last Dec. 1, 14 officers from a counterinsurgency unit of the police were killed in the most deadly attack of 2014. Weeks earlier, people thought to be Naxalites killed a nephew of the president of Dantewada’s Bar Council. At a condolence meeting, however, lawyers and judges directed raw feelings toward JagLAG, questioning its motives and political affiliations.

Even a simple mention of JagLAG can unleash a stream of invective in some antiterrorism and law-enforcement circles.

“All you people are responsible for this havoc,” said S.R. Kalluri, the inspector general of the police based in Jagdalpur, referring to the JagLAG lawyers and a reporter who accompanied them to Dantewada. “I know very well you are Naxalite supporters.”

Even prominent national activists have been arrested under suspicion that they sympathize with the Naxalites. Binayak Sen, a doctor and civil liberties advocate in Chhattisgarh, was sentenced to life in prison in 2010 on charges of sedition that many say were based on fabricated evidence. Twenty-two Nobel laureates signed a petition protesting his incarceration, and the European Union sent observers to monitor his trial.

“The police and the state are showing a classic terrorism-era attitude here — you’re with us or against us,” Ms. Gera said. “But really, there are other options.”

A version of this article appears in print on March 2, 2015, on page A4 of the New York edition with the headline: Shoestring Legal Aid Group Helps Poor in Rural India.