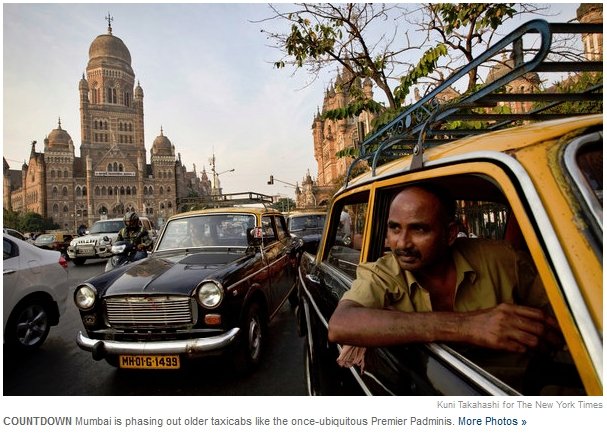

MUMBAI, India: ON a recent evening on Marine Drive here, Amrit Jaiswal, clad in an all-white taxi driver’s uniform, sat in his weathered black-and-yellow Premier Padmini cab waiting for rush hour.

On his dashboard sat a shrine to the Hindu goddess Durga. A plastic likeness of the monkey-god Hanuman hung from his rearview mirror, and the entire interior was covered in floral-patterned gray velour. As the sun sank behind the Arabian Sea, Mr. Jaiswal flipped on a red dome light that gave his cab’s interior the louche atmosphere of a bordello.

To Mr. Jaiswal, 49, who owns his 1994 model Padmini after years of loan payments, the car represents freedom. “The car is strong, it gets good mileage, parts and maintenance are cheap, and if it breaks down you can find a mechanic anywhere,” said the mustachioed taxi driver, who wore several days’ worth of gray stubble. As for the decorations, he said, “I want it to look attractive to the customer.”

|

Multimedia |

Mr. Jaiswal, who paid around $2,900 for his car and license, will feel the loss acutely. “I’m proud to be the owner of this car, but I’ve got only seven years to go,” he said, adding that he could not afford a modern car to replace it. “It’s scary.”

With 58,000 Padmini taxis on the streets in the car’s mid-1990s heyday — countless others were driven by private citizens — Mumbai had the highest density of one car model of any city in the world, according to A. L. Quadros, general secretary of the Mumbai Taximen’s Union. Today there are only 9,000 left, he said, most of them ramshackle but still reliable.

Some in Mumbai are not sentimental about the car’s slow disappearance. “It represented all that was wrong with India’s highly regulated socialist economy,” said Hormazd Sorabjee, the editor of AutoCar India magazine. “The quality was appalling, yet there was an eight-year waiting list to get one.”

A taxi driver, Manoj Yadav, 45, said that his 1995 Padmini was in “A-1 condition,” but conceded that “most customers prefer the new cars.” These include the fuel-efficient Tata Indica and Hyundai Santro small cars and the Maruti Suzuki Omni microvan.

Though the Padmini’s notoriously sticky door handles have a habit of popping off in customers’ hands, and passengers can often see the road through holes in the floorboard, the Padmini still has its adherents, primarily because it is slower and therefore perceived as safer than zippy newer models. And because the Padmini was the first car many Indians rode in, it stirs up wistful feelings.

The Padmini has its roots in a 1952 license agreement that allowed Premier Automobiles of India to produce a version of the Italian Fiat 1100, or Millecento, said Maitreya Doshi, Premier’s managing director.

In socialist-leaning post-independence India, the auto industry was tightly controlled. “The government believed we were making a luxury product, and there was an attitude that it really should not be part of India’s growth story,” Mr. Doshi said. Changes to prices, production or to the car itself had to be cleared by the government, he added, and requests were routinely refused. Production was capped at 18,000 cars a year, he said, though demand was much higher and taxi sales were subsidized.

The government insisted that the car become indigenous. By 1973 Fiat was out, and the Millecento became the Premier President until a bureaucrat objected to the name, which he said denigrated a government office. From 1974 until production finally wound down in 2000, the car has been the Padmini, named for a 14th-century Rajput princess. To the company’s chagrin, many still call it a Fiat.

The remaining Padminis that patrol Mumbai’s roads today are essentially Fiat 1100Ds, circa 1963.

Until the early ’80s, only one type of car in each class was produced in India. There were the small, sporty cars made by Standard Motor Products, which were indigenous versions of a British Standard-Triumph, and the bulbous Hindustan Ambassador, a copy of a 1956 Morris Oxford III that is still favored by many government officials. The four-door Millecento was the car for those aspiring for the middle class.

In the early ’70s, Mr. Doshi said, taxi drivers began switching from Ambassadors to Padminis because they were more fuel-efficient and easier to drive. “It became the preferred brand, although there was not much to compare it to,” he said.

Padminis excelled as taxis in Bombay — as the city was known until 1995 — because they had a large trunk and their 1.1-liter 4-cylinder engine provided a good power-to-weight ratio, Mr. Doshi said. “It had lots of cargo applications,” he added. “So you’d see film crews with five people inside, their paraphernalia on the roof, stuff in the trunk and this little car coughing and sputtering and carrying on, able to pull the load.”

A few modifications were made, with the most exciting ones coming in the mid 1970s. “When we started offering a floor shift and bucket seats it created so much hype in the city,” Mr. Doshi said. “They were perceived as the differentiator between the young and cool and the old and fuddy-duddy,” he said. “And, as a sort of ‘wow’ accessory, we used to offer seat belts.”

Air-conditioning and diesel engines were offered in the mid ’80s. (Since 2002, all metered taxis have been converted to run on natural gas.)

Because the Padmini was such a basic car, it allowed owner-drivers to make their own modifications, or to decorate the cars as they saw fit.

“It was a simple car,” said Adil Jal Darukhanawala, editor of the ZigWheels car magazine. “No electronics, no frills. It was like an Indian version of the Ford Model A, and you could modify it to your heart’s content.”

Loud patterns adorned the interiors, and the bodies and windows were covered in decals announcing the driver’s home neighborhood, nicknames like “Night King” or “Big Boss” or titles of Bollywood songs.

The first ominous sign for the Padmini came in 1983 with the introduction of the compact Maruti 800 “people’s car,” which owed more to Japanese engineering, courtesy of a Suzuki joint venture, than to Indian state planning. After import restrictions were loosened in 1991, foreign cars began to stream into India, making the Padmini seem like a dinosaur.

Mr. Doshi, the Premier executive, said the end was hastened when cabdrivers started replacing their worn-out motors with Kubota marine engines that coughed black smoke and gave the Padmini a reputation as a serial polluter. Production finally ceased in 2000.

The demise of the Padmini has had a corollary effect on the ancillary industries that grew to support it. “There were people who were experts in interiors, or repairing worn-out parts, or fixed cars that had been in accidents,” said Manohar Mistry, whose shop, Swami Arts, creates custom decals made by layering bright-colored stickers. Now, repairs are done by the dealerships, he said.

Mr. Mistry said his business had declined to less than half what it used to be. “The new cars come completely decorated with whatever details you want,” he said, showing a reporter a photo of his magnum opus, a rear window-obscuring decal depicting a 17th century warrior-king prying open the mouth of a lion. As vision-restrictive as they may be, such stickers are no impediment to the cars’ passing an annual inspection.

Since Padmini taxis started disappearing, collectors looking for parts have also suffered. “Fewer and fewer cars are coming to scrap,” said Karl Bhote, a member of the Fiat Classic Car Club of India. “It is unbelievable how much things have dried up in the last two years.”

But Mr. Bhote said that as the Padmini taxi disappeared, he had seen a surge of enthusiasm among collectors. “Nostalgia is kicking in,” he said.

Because of the dearth of parts, Rony Vesuna, a vintage car collector, has put as much effort into accumulating the spare Fiat and Premier parts that fill his Mumbai apartment as he has into restoring his 1973 Premier President.

Mr. Vesuna, who also has six Fiats, said he’d like to see a few restored Padminis remain on the road as heritage taxis.

“The Fiat, especially the taxi, is an iconic figure for Bombay,” said Mr. Vesuna, who like many Mumbai residents still uses the old name for the cars. “I want to pick up a taxi or two for my collection before they are all phased out.”

Still, it’s doubtful that commuters will mourn their demise for long. “I happened to hail a Padmini the other day,” said Mr. Darukhanawala, the ZigWheels editor. “The fact that you can hardly open the rear door to get in and out makes you realize how archaic it is,” he said, alluding to the infamous inoperative door handles.

“On an emotional level it’s terrific, because to a certain generation it was the attainable car of our dreams. But life moves on and the benchmark changes.”