| Service to the needy and poor is service to God. Hats off to Mr.Sawla. |

|

A young man in his thirties used to stand on the footpath opposite the famous Tata Cancer Hospital at Mumbai and stare at the crowd in front- fear plainly written upon the faces of the patients standing at death's door; their relatives with equally grim faces running around.. These sights disturbed him greatly.. Most of the patients were poor people from distant towns. They had no idea whom to meet, or what to do. They had no money for medicines, not even food. The young man, heavily depressed, would return home. 'Something should be done for these people', he would think. He was haunted by the thought day and night. At last he found a way- ....source Read the rest of the story about this Good Samaritan and the service he has dedicated himself to.... |

![]()

| Cancer Ward: Open to the Skies | Chirodeep Chaudhuri |

|

Since Solzhenitsyn, the idea of the cancer ward has always been a sterile place, where those who have this dreaded disease are segregated from society. But in the city in which I live, there is a cancer ward open to the sky.

It was easy to see this as yet another manifestation of the failures of a third world nation, the lack of medical infrastructure. But over the next few months I found the story behind the story. There are secular and religious institutions that will offer these patients a bed but often they are crowded, even claustrophobic, as one patient put it. Sometimes, they are far away and a patient may be too weak to make the trek to and from the home. And anyway, when 43,000 new patients arrive every year, some are going to end up on the street, especially since 70 percent are treated free of charge. The patients who lie down on the street are not resigned to their fate; they are waging a determined battle against it. They do not want to die. They want to live and they will do what it takes to get better again, even if it means recuperating from the savageries of radiation therapy in the dust thrown up by passing cars and huddling under plastic sheets when the torrential sub-equatorial monsoons wash the city. I leamt that a community grows among these cancer patients and their family members who have made the journey from various comers of India’s rural heartlands to the Tata Memorial Hospital. But these impressive numbers also contribute to the one thing that brings all these people together: an infinity of waiting. They wait endlessly, for an appointment with the doctor, for a diagnosis or a result of a test, for their turn at an operation or at a chemotherapy session, and finally, the wait to get better. The plight of the pavement patients has triggered a number of philanthropic responses. Some provide free nutritious meals or distribute tarpaulins and blankets for protection against the weather. And in a city where fights over water are not uncommon, the inmates of a nearby chawl (one room tenements with common toilets and bathrooms) are magnanimous enough to allow the families to fill water from the communal taps. When your water supply is measured in hours per day, this is genuine sharing. Some may die on the street. Many more will survive. They will go back to the back-breaking work of scratching a living from the soil and return each year for an annual check-up. But while they are here, they are a community that shares an enemy: cancer. They battle the rain and the flies. They learn to live with the cacophony of the city’s traffic and the way pedestrians may intrude upon their space at will. They bathe. They eat. They find time to play and laugh and gossip and grumble. They look out for each other and guard each others belongings. They forge a community and they refuse to admit defeat. As a manifestation of the transcendence of the human spirit, the community of temporary residents of Lady Jerbai Wadia Road is hard to beat. Babanrao Pandurang Gawli. District - Thane, Maharashtra

For days on end I saw this man sitting motionless, staling blankly at the busy road in front of him. He resembled a skeleton draped in an oversized shirt and a pair of loose navy blue shorts. His only movement was when he picked up the plastic container to spit or to adjust the tube emerging from his throat and in to his nose.

As the weeks passed I sometimes saw Babanrao walking about with the help of a stick. And then one day they were gone.. .and in their place were the belongings of another patient.

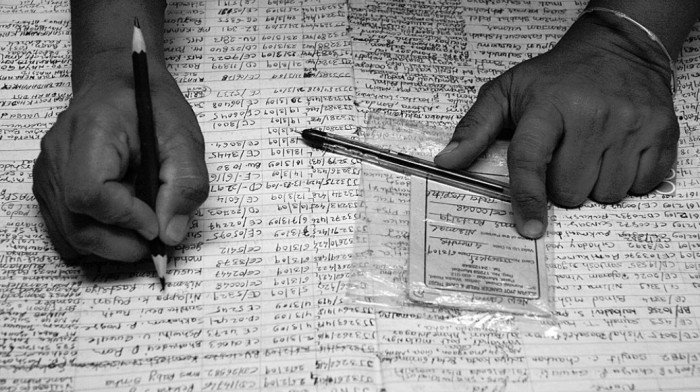

Ismail, 21, the elder of the two brothers remembers how the family went into shock when they first heard the news about the cancer. “These are all fancy diseases...we call them raja-maharajaon ki bimiriyan... At home everybody wondered how this fellow could get cancer?” he said with a little laugh trying to humour his brother. ............................. Jeevan Jyot Trust [see below - ED]  Today, he runs the Jeevan Jyot Trust providing free medicines and meals to nearly 250 needy patients and their families each day. His hole-in-the wall office in the lane adjoining the hospital sees a steady flow of patients who arrive with all sorts of queries - how to organize funds for treatment, places to stay or simply to make sense of the maze of the hospital's system. Sawla and his team patiently sit through it all providing moral support if other requests are hard to meet. “This is my prayaschit (expiation) for the wrong I did by not helping that man,” he says.

After a short prayer, the food distribution begins. Like the Jeevan Jyot Trust, this free distribution of food referred to as Khichdi Ghar is a philanthropic undertaking of the Shri Vardhaman Jagriti Yuvak Mandal - a Jain trust many of whose members are small traders and shopkeepers from the neighbourhood. Breakfast usually consists of khichdi (a thick paste of rice and lentils), milk, rotis, and seasonal fruit. Lady Jerbai Wadia Road attracts its fair share of philanthropies. In a city notorious for water shortages, the residents of a nearby tenement have provided free access for the patients to the community tap in their premises. Virendra Kumar Gupta, a patient and his wife maintain that the real problem on the pavement is not food, but water. “One has to admit.. .whatever the troubles one may have here.. .the filth, the mosquitoes, the noise.. .no one will ever sleep hungry,” they said. During the mid-aftemoons, one doesn't see too many of the patients here on the pavement since many may have gone across the road to keep their appointments with their doctors. What are left behind are their belongings - clothes, utensils, medicines and documents. “It is all safe here.. .nothing is ever stolen. We too keep a watch over the belongings of those staying around us,” Manoj Shah, who has been staying on this pavement for more than a year now, had mentioned to me once. The monsoons were to hit the city a few months after I started this project. Kunwarpal, who was sitting waiting for his brother and sister-in-law to return from inside the hospital said one day, “My greatest worry now is about what will happen during the rains...we have to ensure that our reports and documents are safe and dry.” ...........There is a lot more here Bio: |

Chirodeep Chaudhuri replies to one of the comments received from Geetali:

Dear Geetali...Thank you for your comments. I am especially glad to find that you have commented on the texts. I am not sure this would have worked without the accompanying text and the case studies that help to create the full portrait. because, Like you pointed out correctly, I felt, just the pictures would have been very voyeuristic. A "story" like this is very easy to do photographically because there is so much inherent drama and pathos there that even a poorly conceived work would get a sort of "pseudo-bleeding heart" response. But it may not necessarily inform fully or even accurately...which was my prime concern. So, thank you once gain for your comments.

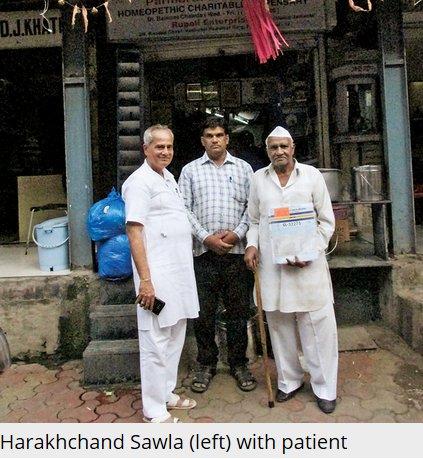

| Harkhchand Sawla |

|

Dressed in a white kurta and pyjama, Harakhchand Sawla can be seen taking a walk around the premises of Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH) in Parel everyday from afternoon till late evening, talking intently to those who are generally overlooked by passers-by, the cancer patients that camp outside TMH. Sawla has been tending to the patients and their relatives, teeming on roads leading to the hospital. Around 12:30 pm for lunch and 6:30 pm for dinner, patients queue up outside his tiny office in a nearby chawl with plates and glasses, and are served hot meals — rice, chappatis and vegetables. "For those who have undergone rigorous chemotherapy sessions or have throat cancer and can't digest salty food, we serve turmeric-infused milk," says Sawla.

"In the vicinity of TMH alone, the number of patients that come to us for meals has risen to 400," he says. But that hasn't deterred this Mulund resident. From reuniting family members to helping out by providing free medicines or giving an appropriate funeral to the deceased, who have no one to fall back on, Sawla's trust spends up to Rs8 lakh every month towards social work. "A few of them are so dedicated that once a patient completes his/her treatment, s/he escorts the unattended patients back to their remote villages across India and reunite them with their families," he says. Fond of children, he says it pains him to see little ones affected by the dreaded disease. He recently took around 400 children for a day's outing. "We have regular activities for children to keep them occupied and distance them from the pain that cancer can inflict. We convince people to collect and submit old medicines, toys, clothes and books for the kids. I appeal to more people to come forward and help us in our endeavour of making the lives of cancer patients a tad better," he adds. Do your bit |

When I first visited Lady Jerbai Wadia Road, a small back lane in central Bombay, there was nothing to distinguish this little community of 15 to 20 families from all the millions of residents of this city who live on the pavements. The difference lay in the details: the child wearing a medical mask and playing with a cat, the way a woman smiling at me from under a tree had covered her thinning hair with a jaunty head scarf; and a plastic bag hanging on a railing, a plastic bag marked “CT Scan". These are the patients on the pavement, the spillover from the Tata Memorial Hospital, Asia's largest cancer treatment facility.

When I first visited Lady Jerbai Wadia Road, a small back lane in central Bombay, there was nothing to distinguish this little community of 15 to 20 families from all the millions of residents of this city who live on the pavements. The difference lay in the details: the child wearing a medical mask and playing with a cat, the way a woman smiling at me from under a tree had covered her thinning hair with a jaunty head scarf; and a plastic bag hanging on a railing, a plastic bag marked “CT Scan". These are the patients on the pavement, the spillover from the Tata Memorial Hospital, Asia's largest cancer treatment facility.

Many patients, however, complain of the claustrophobic environs of some of these places. Bishwanath, one such patient, from Uttar Pradesh, said he was scared that he would catch more infections at these places. Others like Shyamal Chowdhuri, from West Bengal, prefer to “sleep under the trees” as he simply prefers the open skies.

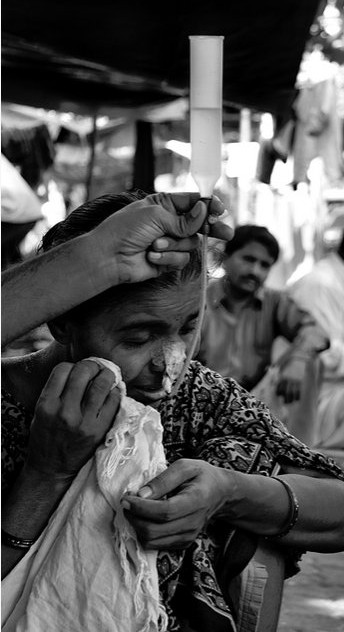

Siadulari, from Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, (pictured here), and her family decided to reside here because they felt the nausea caused by her radiation therapy would make it difficult for her to travel to the hospital in the buses that ferry patients to and fro from these homes for their appointments. Giijashankar, her husband points out, “For the women patients the biggest problem is using the latrine”.

Many patients, however, complain of the claustrophobic environs of some of these places. Bishwanath, one such patient, from Uttar Pradesh, said he was scared that he would catch more infections at these places. Others like Shyamal Chowdhuri, from West Bengal, prefer to “sleep under the trees” as he simply prefers the open skies.

Siadulari, from Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, (pictured here), and her family decided to reside here because they felt the nausea caused by her radiation therapy would make it difficult for her to travel to the hospital in the buses that ferry patients to and fro from these homes for their appointments. Giijashankar, her husband points out, “For the women patients the biggest problem is using the latrine”.

Thirty years ago, he left his thriving business and began caring for cancer patients by adopting 25 of them, looking after their nutritional needs. Sawla now has a dedicated army of up to 150 volunteers who assist him. Sawla's trust, Jeevan Jyot [see below also - SikhNet ED], also caters to the need for meals of 700-odd patients or their relatives at state-run hospitals — JJ, St George, Cama and TMH. The trust incurs a daily cost of Rs12,000 in feeding these patients.

Thirty years ago, he left his thriving business and began caring for cancer patients by adopting 25 of them, looking after their nutritional needs. Sawla now has a dedicated army of up to 150 volunteers who assist him. Sawla's trust, Jeevan Jyot [see below also - SikhNet ED], also caters to the need for meals of 700-odd patients or their relatives at state-run hospitals — JJ, St George, Cama and TMH. The trust incurs a daily cost of Rs12,000 in feeding these patients.