In recent weeks, Sikh sites on the Internet have fostered an energetic discussion on 'same sex unions'. I enter this debate with a great deal of trepidation. The conversation is necessary; hence this essay, written a few years ago, is being reproduced today.

In recent weeks, Sikh sites on the Internet have fostered an energetic discussion on 'same sex unions'. I enter this debate with a great deal of trepidation. The conversation is necessary; hence this essay, written a few years ago, is being reproduced today.

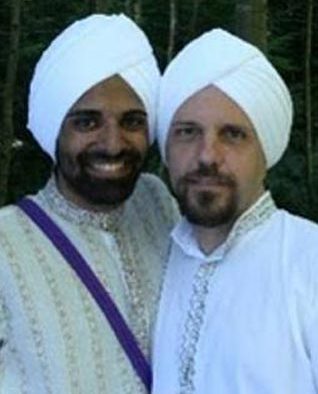

On July 19, 2005, Canada became the fourth nation to fully legalize same sex marriages. During the stormy national debate that preceded it, Navdeep Singh Bains, a young Canadian Sikh Member of Parliament and lawmaker, garnered significant notoriety and considerable abuse from his fellow Sikhs for supporting the legislation.

The highest seat of Sikh temporal authority, the Akal Takht in Amritsar, Punjab, also joined the fray; its jathedar - egged on by other members of the Canadian Parliament - quickly censured the Canadian law and exhorted Sikhs to reject it. Canadian gurdwaras immediately weighed in with statements condemning Canada's legalization of same sex unions.

Sooner or later, this Pandora's box had to be opened. The question of "gay marriages" will neither go away, nor should it.

The Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Portugal, Denmark and, most recently, South Africa have taken the bold step of embracing and legitimizing same sex unions after considerable soul-searching. Others, like the United States, seem poised at the brink but find the question terrifying; the issue remains mired in interpretation of Christian doctrine by some, and in state versus federal rights by others.

For instance, voters in Maine plan a referendum that will decide, for the third time, whether to add sexual orientation to the state's human rights act that already prohibits discrimination based on sex, race, color, marital status, religion, ancestry or national origin.

Very much aware of the minefield I am stepping into, what I aim to do is not to propound a view written in stone, but to explore the issue from a Sikh humanitarian perspective - in other words, to foster a debate. Judgments and decisions will evolve, but that time is not now and not yet. It is time to explore, to debate and discuss.

What is the Sikh position to be?

We like to think of love and marriage resulting in family to be as indivisible as horse and carriage. But the institution of marriage and family, like the horse and carriage, is in constant flux, evolving and changing dramatically over time.

Marriage-and-family was at one time a politically and socially mandated economic institution, protecting the rights of men, women and their children while delineating the duties of each. It was necessary for families to have children if for no other reason than to increase the labor pool.

In support of this contention, I offer the fact that, in the upper classes, a man was expected to acquire a second wife if no children resulted from the first marriage; in Europe, the poorer classes and peasants would not marry until a premarital pregnancy provided proof of fertility.

The question of same sex marriages was moot, although same sex couplings have existed probably as long as humans have, and even longer in the animal kingdom. Although ancient Greeks received attention for bisexual and homosexual conduct, I doubt that other cultures were free of it. For instance, I point to the eunuch culture that has existed in Indian society for ages. Until very recently, in most societies, including Indian, gays were effectively closeted and never publicly acknowledged.

But socio-economic realities have changed, spurred largely by the industrial revolution and advances in reproductive technology. Now having a child is now a choice, as is the decision to marry or to continue with a marriage; these are no longer matters dictated by economic or societal imperatives. Marriages are now increasingly driven by love or become mergers dictated by other considerations, where the roles of the individuals are negotiable and flexible.

These societal changes open the door to the argument that gay and lesbian couples can participate in modern society as a family unit just as well as heterosexual couples. It follows, then, that to deny them such opportunity is to abridge their human dignity and their rights of citizenship.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to deny that gay citizens have equal rights in a just and free society. There is mounting biological evidence of a propensity for gay behavior, if not of a gay gene. I don't know if homosexual behavior is entirely or only partially driven by differences in DNA or if being gay is the sin that some Bible-thumpers would have us believe, but to deny gays any of their basic human rights would certainly be sinful.

A marriage is a civil union when a court or some such legally controlling authority performs it. Such an act speaks of a legally binding, contractual obligation that is needed for protection of the individual participants as well as of the society. I could, therefore, argue that there is no basis for denying gays and lesbians such civil licenses, even though, traditionally, marriages have been defined as only between heterosexual partners. Even common-law marriages are legal recognition of only heterosexual unions.

Sikh tradition and teaching speaks of human dignity that is inviolate and of relationships that are not exploitive or manipulative. I believe my position to allow same sex unions is consistent with this.

The next question is whether Sikhism would allow same sex marriages to be performed within a gurdwara by the same rites (Anand Kaaraj) as heterosexual marriages. And here we are in absolutely uncharted territory.

The next question is whether Sikhism would allow same sex marriages to be performed within a gurdwara by the same rites (Anand Kaaraj) as heterosexual marriages. And here we are in absolutely uncharted territory.

Remember that in the four lavaa(n) of Anand Kaaraj, there is no mention that the hymns are directed to a heterosexual couple; in fact, these hymns are metaphors for the development of the relationship between the human and the divine.

Guru Granth and Sikh teachings do not offer us a slate of unambiguous do's and don'ts; Sikhism does not micromanage our life. What it does offer us is an ethical framework of universal values within which to negotiate our ethical dilemmas.

For most people, marriage remains a sacrament that must be solemnized in sanctified space, where the presence of the unifying higher power of God can be felt. Even if they visit their places of worship no more than twice in their lifetimes, most people absolutely want the imprimatur of their religion before they feel decently married. Remember that religions provided the earliest organized structure for human societies with codes of conduct for their adherents that antedate civil societies.

Most religions have categorized a vast array of sins of omission and commission that place those followers who commit them outside the realm of those accepted to be in grace. Until they atone for their departure from the path, such people may have some privileges of institutional religion withheld from them, and they may be barred from participation in certain rites. For example, a divorced Roman Catholic may not easily receive Communion or be remarried in the Catholic Church.

Since a family - consisting of the mother, father and children, if any - forms the nucleus and the smallest functioning unit of society, most religions have sanctified this unit at the core of their teaching. In the view of most religions, then, gay and lesbian couples do not fit the definition of an acceptable unit of society. Even though they look to a universal loving creator, religions have to be lived here on earth. Most religions thus have difficulty sanctifying or accepting the union of same sex couples.

The question of same sex unions has only recently surfaced in Sikh society, not because gay Sikhs do not exist, but probably because in the Indian culture they remain closeted and do not occupy public space or public consciousness. I have come across one article (in Punjabi) by Gurbaksh Singh Kala Afghana on this issue; with a plethora of suggestive and indirect citations from gurbani, he rejects the idea of same sex unions.

One recent commentary in English by two Sikh-Canadian lawyers, T. Sher Singh and Ramandeep Kaur Grewal, argues that for Punjab-based Sikh religious leaders to venture authoritative Sikh opinions on the Canadian legal debate was inappropriate as well as unnecessarily intrusive to the internal affairs of Canadian society - especially when those sitting in judgment in distant Punjab had neither solicited nor entertained any submissions from those directly affected by the proposed law.

In its scripture or its tradition, Sikh teaching appears to say nothing at all about same sex couples, but it does speak at length of core ethics wherein the dignity and rights of every human are sacred; where compassion and fairness govern human conduct. It follows, then, that the rights of those who follow a gay lifestyle should be equally acknowledged and never abridged.

Should homosexual Sikhs be discriminated against?

I would say no, neither in the gurdwara nor outside of it. Judge not others, the Gurus would say, but make your own life sublime. This would mean judge not those who follow a different beat.

I would think, therefore, that Sikhism would be tolerant and non-discriminatory. By this logic, there would be no reason to ban a gay Sikh from any activity in the gurdwara in any capacity, from the managerial to the preparing and serving of the parshad or langar, and even in the reading from Guru Granth or in leading the congregational prayer (ardaas).

Some might be uncomfortable with my position here because many of these activities seem to cast the gay person as a role model for the community, but I mention them so as to spur discussion and debate.

Some might be uncomfortable with my position here because many of these activities seem to cast the gay person as a role model for the community, but I mention them so as to spur discussion and debate.

It seems to me that homosexuality should be accepted and tolerated, but not necessarily held as a laudatory model lifestyle. If we recognize that some people are different (biologically or behaviorally), we can then accept their difference. And in practice, Sikhism, I believe, has been quite tolerant for one rarely hears of homosexuality and never of any discrimination. But then, this may be the natural result of an Indian culture where sexual intimacies are never publicly acknowledged.

On the other hand, much of Sikh teaching is couched in metaphors from family life. Even the adoration of God is explored in terms of the closest relationship that humans can comprehend - that between a man and a woman. The heterosexual relationship is defined as sacred in Sikhism; an honest family life is described as the first duty - the primary religion of humans.

This must be kept in mind while we debate same sex unions.

From the perspective of nature, same sex unions clearly are at best sterile, nonproductive ones. A heterosexual union, on the other hand, holds the promise of being naturally productive. Same sex unions, some would argue, go against the biological laws of nature and are, therefore, against the laws of God; and laws of God cannot be denied.

Let's apply Kant's categorical imperative here: If everyone were to do what I recommend, would the world be a better place? If everyone were gay, the world would surely end because the gay union cannot be biologically fertile. Sex is meant to be a creative reproductive force. This reasoning lies at the core of religious rejection of same sex unions.

Yes, I know that modern reproductive technology can surmount such limitations, and also that not all heterosexual unions produce successful parents or children who contribute to society. Does this call for religions to withhold their approval of same sex unions? It is this that surely puts us in a pickle.

It seems to me that institutional religions must preach, as in fact they do, kindness, compassion and equal acceptance of all people, regardless of their lifestyle or sexual orientation. But each religion must also be able to withhold its imprimatur from a certain way of life in its institutional framework.

Since religions have the right to determine if certain sacraments are to be denied to a follower judged as not being in a state of grace, a denial of the right to a religious wedding, it seems to me, is not a human-rights issue. It is a matter to be decided by the adherents of a religion according to their traditions and teachings. A denial of recognition of same sex unions within a religious practice would, I believe, be outside the jurisdiction of the civil judicial process.

In other words, a religion may deny a religious wedding ceremony for same sex couples in a church or a gurdwara while at the same time insisting on equal rights for them in society.

The Sikh code of conduct (Rehat Maryada) speaks volumes on marriage, but only that of heterosexual couples; same sex unions remain unmentioned, and this could be viewed as a tacit rejection of such conduct. My interpretation of the question here - same sex unions - is deliberately narrow.

For instance, it cannot be stretched to approve polygamy as seen in some societies, such as that of the Mormons. (Even the Mormons have now changed their code to conform to mainstream U.S. society. They no longer officially approve polygamy, though it is still practiced.) In Sikh belief, such relationships in contemporary society would, by their very nature, be manipulative or exploitive and diminish the sacred intimacy of the relationship.

I know that I am leaving the issue unsettled. That is deliberate, but it is not a delaying tactic. The issue is such that we will not and cannot remain immune from it. It is too important to be left only to preachers whose thinking is circumscribed by the cultural realities of Punjab and India. It is one of those major constitutional and legal issues that societies face from time to time and that are never resolved in a day, a week, a month or even a year.

Let's join the discussion and see what evolves. Let's wait to draw lines in the sand.

This is an edited version of the piece which first appeared in The World According to Sikhi, by I.J. Singh, The Centennial Foundation, Toronto, Canada, 2006.