When people search for justice - what, exactly, does that mean? Harm creates an imbalance in a person’s mind and emotions. Violence, theft, murder, rape. All of these activities involve one or more people overpowering another person. When someone treats me or someone I love in a way that causes me pain, and is against my will - that imbalance longs to be corrected. “Justice” is the self-defined process by which balance gets re-established in the face of some harm.

Many traditional paths to justice involve either vengeful or punitive measures. However, more and more people are investigating models of justice that seek to re-establish the balance by restoring the human relationship between perpetrators and victims.

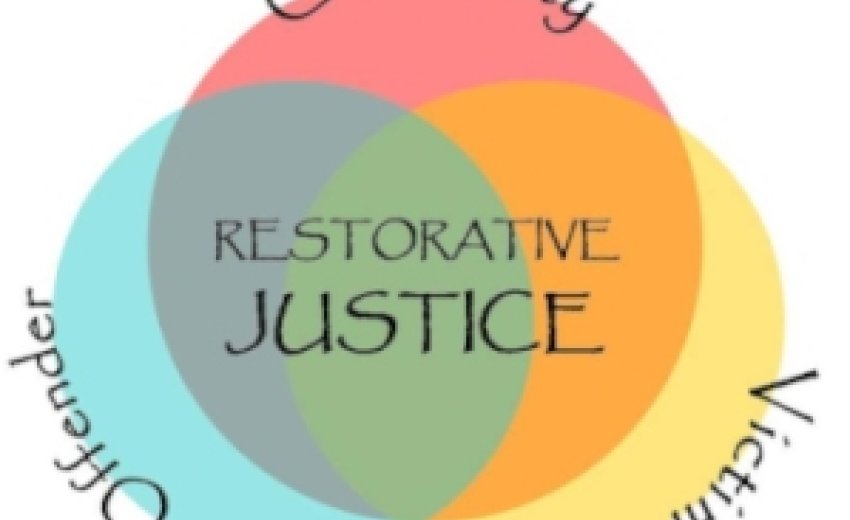

The Restorative Justice process is one such model.

The Restorative Justice process is one such model.

When it comes to the events of 1984 and their aftermath, the Sikh community may find some intriguing roads forward by exploring alternative justice models such as this one.

From: www.restorativejustice.org

Restorative justice emphasizes repairing the harm caused by crime. When victims, offenders and community members meet to decide how to do that, the results can be transformational.

Restorative justice emphasizes non-violent methods of recognizing, acknowledging and repairing the harm caused or revealed by criminal behavior. It can only be accomplished through a cooperative processes that include all stakeholders, those who caused the harm along with all those who have been harmed.

Practices and programs reflecting restorative purposes will respond to crime by:

-

identifying and taking steps to repair harm,

-

Involving all stakeholders, and

-

Transforming the traditional relationship between communities and their governments in responding to crime.

Three principles form the foundation for restorative justice:

-

Justice requires that we work to restore those who have been injured.

-

Those most directly involved and affected by crime should have the opportunity to participate fully in the response if they wish.

-

Government's role is to preserve a just public order, and the community's is to build and maintain a just peace.

Restorative programs are characterized by four key values:

-

Encounter: Create opportunities for victims, offenders and community members who want to do so to meet to discuss the crime and its aftermath. Harm caused on all levels is spoken and heard by all parties.

-

Amends: Expect offenders to take steps to repair the harm they have caused.

-

Reintegration: Seek to restore victims and offenders to whole, contributing members of society.

-

Inclusion: Provide opportunities for parties with a stake in a specific crime to participate in its resolution.

Some of the programs and outcomes typically identified with restorative justice include:

-

Victim offender mediation - involves a voluntary meeting between the victim and offender facilitated by a trained mediator. With the assistance of the mediator, the victim and offender begin to resolve the conflict and to construct their own approach to achieving justice in the face of their particular crime. Both are given the opportunity to express their feelings and perceptions of the offence (which often dispels misconceptions they may have had of one another before entering mediation.) The meetings conclude with an attempt to reach agreement on steps the offender will take to repair the harm suffered by the victim and in other ways to "make things right". The mediator's role is to facilitate interaction between the victim and offender in which each assumes a proactive role in achieving an outcome that is perceived as fair by both

-

Conferencing - The roots of conferencing are found in the whanau conference of the Maori, aboriginal peoples to New Zealand. With their strong extended family and kinship relationships, the Maori had been using whanau conferences as a means of dealing with their own youth. Conferencing is used only when the offender admits guilt (or in some jurisdictions, admits liability or declines to deny guilt). It is not used to determine guilt, and at any time during the process the offender may choose to bring the conference to a halt and proceed to court for a traditional determination of guilt or innocence. During the conference, the offender begins by telling his/her side of the story, with the victim then subsequently doing likewise. Both then have a chance to express their feelings about the events and circumstances surrounding the crime. Each may then direct questions to one another, followed by questions posed by their respective families. The offender and his/her family then meet privately to discuss reparation, thereafter presenting an offer to the victim and others in attendance. Negotiations continue in the group until consensus is reached. The agreement is put to writing with payment/monitoring schedules included.

-

Circles - Circles are found in the Native American cultures of the United States and Canada, and are used there for many purposes. Circles have been developed most extensively in the Yukon, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. They are also occasionally used in other Canadian communities, and in the United States where Navajo peacemaking courts have also used circles.

As with the restorative processes of mediation and conferencing, circles provide a space for encounter between the victim and the offender, but it moves beyond that to involve the community in the decision making process. Depending on the model being used, the community participants may range from justice system personnel to anyone in the community concerned about the crime. Everyone present, the victim, victim’s family, the offender, offender’s family, and community representatives are given a voice in the proceedings. Participants typically speak as they pass a “talking piece” around the circle. The process is value driven. Primarily, it is designed to bring healing and understanding to the victim and the offender. Reinforcing this goal of healing is the empowerment of the community to be involved in deciding what is to be done in the particular case and to address underlying problems that may have led to the crime. In reaching these goals, the circle process builds on the values of respect, honesty, listening, truth, sharing, and others.

Participation in the circle is voluntary. The victim must agree to attend without any form of coercion. The offender accepts his/her guilt in the matter and agrees to be referred to the circle. Especially for the native communities, it is important for the offender to have deep roots in the community. Each circle is led by a “keeper”, who directs the movement of the talking piece. Only the person holding the object is allowed to speak, ensuring that each person has an opportunity to be heard.

As the talking piece makes the rounds of the circle, the group discusses different topics. In addressing the crime, participants describe how they feel. For the offender, this includes why he/she committed the crime. For the victim and each of the community participants, the circle provides an opportunity to explain the impact the crime has economically, physically, and emotionally. Through this process of sharing the participants are able to develop a strategy for addressing the crime (i.e. restitution, or community service) and the causes of the crime.

-

Restitution - Institutionalized restitution dates back to ancient times. Under the Babylonian Code of Hamumurabi (c. 1750 B.C.) victims were entitled to receive payment for certain property offences. Mosaic law required thieves to repay oxen to victims from whom they had stolen oxen. The Roman law of Twelve Tables (449 B.C.) prescribed repayment schedules for theft of property according to when, and under what circumstances, the thief stole and handed over the property. In the case of violent offences, Middle Eastern codes, such as the Sumerian Code of Urnammu (c. 2050 B.C.) and the Code of Eshnunna (c. 1700 B.C.) required restitution. In the ninth century in Britain, offenders were required to restore peace by making payments to the victim and the victim's family. The main purpose of institutionalized restitution was to prevent retaliatory violence for wrongdoing, providing a more "civilized" means of reparation. Restitution serves to commemorate the gesture of reparation and acknowledgment of wrongdoing. Instead of completely ignoring the harm done to individual victims, restitution acknowledges and attempts to repair the injury they have suffered. Whereas retributive and rehabilitative responses fail to address the harm inflicted on victims, restitution, when sought as an outcome of a restorative process, has as its primary motivation reparation to the victim. Thus, restitution is said to better satisfy a victim's need for vindication, as the offender must personally acknowledge and account for the offense.

-

Community service – is defined as action by the offender to make good the loss suffered by the victim. Here, a meaningful distinction may help maintain the reparative purposes of both restitution and community service: restitution repairs the harm to the individual victim; community service repairs the harm to the community. Who the victim is--individual or community--determines the type of reparative sanction. Distinguishing community service from restitution in this way helps prevent community service from being used as a punitive sanction. If we truly accept the proposition that community is responsible for maintaining peace, and society order, then community service becomes important, within a restorative system of justice, to maintaining peace within the relevant community by repairing the harm crime caused it.

Oprah Explores Restorative Justice on her TV Show