Talk of 'accepting' or 'tolerating' other faiths overlooks the fact that we're all human.

When I was about to become a bride, my mother and father paid the obligatory call on my fiance’s parents. It was the thing to do—Emily Post said so. Too, my parents wanted to get to know these people who would be so important in their daughter’s life. And they had a crucial question to ask, related to our religious faith. I wasn’t there, so I don’t know how they phrased it, but this is how my mother recounted her end of the conversation afterwards: “I wanted to know if they were going to accept you, because accepting you meant that they thought there was something to accept.” Acceptance, in my mother’s view, was not enough.

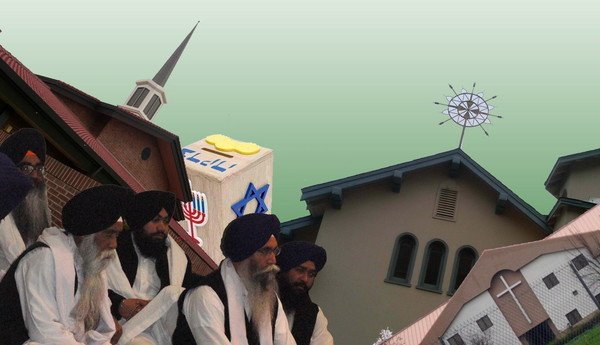

The answer satisfied my parents and I, a Jewish girl, married the son of a Presbyterian minister some months later. I thought of that when I read Sen. Darrell Steinberg’s statement to a Sikh congregation in the wake of the recent shootings of two Sikh men that “Our community can only be safe when we come together and insist not just on tolerance but acceptance.” Words are slippery things, but I think my mother’s “acceptance” and Steinberg’s “tolerance” meant the same thing: the naming of another person as the Other, the NotMe, the One Who Is Different. For Steinberg, as for my mother, defining someone as the Other was part of the problem.

Through circumstance and choice, as a Jew I have spent most of my life in the position of the Other. Does this matter? Obviously not enough for me to change where I live. However, it has made for some misunderstandings.

In Elk Grove, my street seems to be ground zero for Jehovah’s Witnesses. I don’t know if they don’t coordinate their proselytizing, but we often can have different groups of Witnesses knocking on our doors with some regularity. I have neighbors who hide when the Witnesses come calling or rudely dismiss them. That hasn’t been my way. In the beginning, I’d answer the door and listen politely to their opening spiel about the joys of a life with Christ. Then I’d point to the mezuzah on my doorpost and say, “I’m Jewish.”

Initially, I assumed I was telling them they were wasting their time with me. In fact, I was, in their minds, throwing down some challenge: convert this heathen. That never occurred to me—Jews don’t proselytize—so it took a Christian friend to educate me in the concept of evangelism, and she taught me that the only way to not engage a missionary is to cut them off at the pass.

When I was in grade school, there was only one other Jewish family in our town. My closest girlfriends were all Christian, which meant that I spent a fair number of Sundays sitting with them in the pews. I became so practiced in the liturgy of Catholicism that even today I’m somewhat more comfortable at mass than in a synagogue.

There’s a benefit to this: I see the things that connect different religious practices, rather than those that separate us. I know that priest and rabbi often make the same physical movements during their services. I can see where Muslim, Jewish and Christian observations have the same source. When I visited the local Sikh temple a couple of weeks ago on assignment for Elk Grove Patch, I was told that the family of shooting victim Surinder Singh would be saying prayers for a week. Oh, I thought, it’s the Sikh version of shiva, the week-long period of mourning that Jews have for their dead.

When I moved to Elk Grove, it was from a community that had the second largest Jewish population in the United States. I could walk the streets there and not feel like the Other. Except—not really. The same sort of divisions that exist between Christians and Jews, Muslims and Buddhists exist within Judaism as well. There are the Orthodox Jews, the Conservative Jews and the Reform Jews and each has several mini-groups within them. They each have a different understanding of the Torah (the Bible) and thus, they each have different rules for the right way to practice Judaism. They are, to greater or lesser degrees, very protective of their religious positions.

I saw this first hand when I worked with some others to start regular gatherings of the Jewish community in Elk Grove. Yes, there are enough of us here to have a community. However, some of us are Reform, some of us are Conservative, and some are Orthodox. The congregation helping us was Conservative, however, and that seemed to put the kibosh on our efforts.

Despite the rabbi’s assurances that there were no strings attached to his helping us organize, the Elk Grove Jews weren’t quite comfortable with being under the aegis of a congregation not their own. They would rather go without, travel into Sacramento to participate in religious observation, than chance that their community would be commandeered by a different branch of Judaism. It was our loss, and it saddened me, this inability to look past the labels, this insistence on creating the Other even within our own faith.

My in-laws didn’t accept me; I was just one of their kids, married to their oldest son. Likewise, I don’t accept people of other faiths, because, really, there’s nothing to accept. We are all, whatever our spiritual bent, members of the same tribe—the human tribe.