The Sikhs have a long military tradition and have always be at the forefront in serving their country. Over 65,000 Sikh soldiers fought in WWI and over 300,000 in the WW II. This year too, we honor the memory of these brave warriors and recount the unique documented story of Pvt. Buckam Singh.

The Sikhs have a long military tradition and have always be at the forefront in serving their country. Over 65,000 Sikh soldiers fought in WWI and over 300,000 in the WW II. This year too, we honor the memory of these brave warriors and recount the unique documented story of Pvt. Buckam Singh.

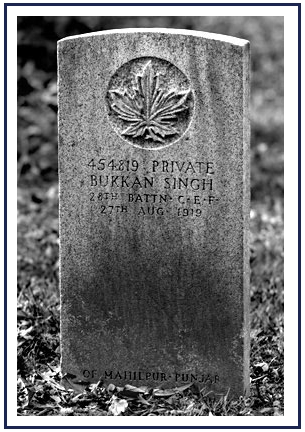

The grave site of Pvt. Buckam Singh at Kitchener Mount Hope Cemetery, is the only military grave of a Sikh soldier in Canada from the World Wars. Wounded twice on the battlefields of France in WWI, Canadian soldier Pvt. Buckam Singh was one of only 9 Sikh soldiers allowed to serve with Canadian Forces in WWI. With the discovery of his war medal and military grave the Sikh community has reclaimed a forgotten son and Canada has reclaimed the story of a hero.

Early Life

Buckam Singh was born on December 5, 1893 at Mahilpur in the Hoshiarpur District of Punjab. His father was Badan Singh Bains and his mother was Candi Kaur. At age 10 on March 1903, Buckam was married to Pritam Kaur of Jamsher in the Jullundhur District of Punjab. It was common in Sikh families at the time to arrange the marriage of their children at a young age. Although married at a young age, the couple would typically not be allowed to see each other or live together until they had reached adult hood when a ceremony called Muklawa would be performed to formally consummate the marriage.

Glimpses of Canada

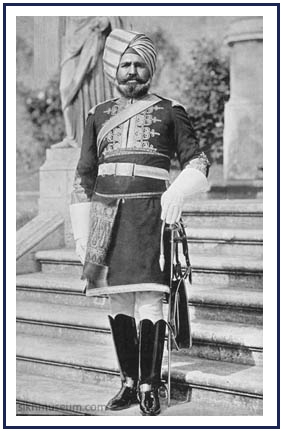

The first Sikhs to visit Canada were soldiers who had been invited to attend the the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in London in 1887. They traveled by railway across Canada and fell in love with the majestic landscape, rich vegetation and fertile farmland of Canada which reminded them in many ways of their Punjab homeland. Once back in Punjab, news spread fast and soon the first Sikhs set sail for a new life in Canada. Buckam Singh joined these early pioneers and at the young age of 14 left for Canada in 1907.

The first Sikhs to visit Canada were soldiers who had been invited to attend the the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in London in 1887. They traveled by railway across Canada and fell in love with the majestic landscape, rich vegetation and fertile farmland of Canada which reminded them in many ways of their Punjab homeland. Once back in Punjab, news spread fast and soon the first Sikhs set sail for a new life in Canada. Buckam Singh joined these early pioneers and at the young age of 14 left for Canada in 1907.

At the time, Sikhs already in Canada, could not bring their families. By denying Sikhs their wives and children it was hoped that within a few years most of the Sikhs in Canada would return to their homeland. Between 1904 and 1920, only nine women were allowed to immigrate to Canada. Buckam Singh’s hopes of one day bringing his wife Pritam Kaur to Canada were dashed.

Immigration laws combined with the unions made sure that the few Sikh immigrants already in the country were only allowed to work on low skill manual labour jobs on farms, the railways, saw mills or mines. Irrespective of their education or background, machinists, doctors or engineers, it did not make any difference as they had no chance of securing a job in their field of study or expertise. The young Buckam Singh worked in B.C.’s mining industry at this time.

Even though Sikhs were succeeding in the few professions open to them, they were still barred from most others. The government laws did not allow Sikhs to vote or hold any public office, civil service job, compete for public works contracts, enter law or pharmacy or buy any Crown timber. Perhaps it was under these conditions that Buckam Singh at age 20 decided to leave British Columbia in 1912/1913 and seek new opportunities and adventure in Ontario.

Buckam Singh is one of the earliest documented Sikhs known to have been living in Ontario. The first documented Sikh living in Ontario seems to be Dr. Sundar Singh who had been sent to Ontario and Ottawa by the British Columbia Sikh community to advocate and lobby on their behalf. Dr. Sundar Singh made a number of public speeches in Toronto between December 1911 and February 1917. After spending nearly two years in Toronto, Buckam Singh worked on the farm of W.H. Moore at Rosebank Ontario. He would spend six months here before deciding to join the military and begin the next chapter of his life.

When Great Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, Canada as a member of the Empire officially entered the war on the following day. This was the first time in her history that Canadian forces fought as a distinct unit under a Canadian born commander.

Initially visible minorities were not welcome. When 50 blacks from Sydney, Nova Scotia volunteered their services they were told, “This is not for you fellows, this is a white man’s war.” By 1915 the rules were relaxed somewhat and minorities including blacks, aboriginals and Japanese Canadians were allowed to join the military, but mainly in segregated units that even traveled and camped separately. It is interesting that Buckam Singh and the 8 other Sikh Canadian soldiers known to have served Canada in The Great War were integrated into mainstream Canadian battalions rather than placed into one of the existing segregated units.

Patriot, The Call to Duty

Leaving the farm of W. H. Moore at Rosebank Ontario in April 1915, Buckam Singh at age 22 made his way to the town of Smith Falls, Ontario to enlist with the 59th Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Buckam Singh formally signed his Attestation Papers on April 23, 1915 swearing his allegiance to His Majesty King George the Fifth and assigned his regimental number: 454819. Buckam Singh was then sent to Barriefield Camp near Kingston for his medical examination and training, the 59th Battalion was commanded at this time by Lt.-Col. H.J. Dawson.

Buckam Singh’s name on the Attestation Paper is recorded as ‘Buk Am Singh’ while he signs his name as ‘Bukam Singh’ . He is listed as 5'-7? in height, with a swarthy complexion. It is interesting to note that the form asks for the recruit’s religious denomination, but only includes the following choices – Church of England, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Other Protestants, Roman Catholic or Jewish. Not very accommodating for a Sikh or anyone of another religion which were typically assigned the default of ‘Church of England’ by administrative clerks.

Leaving the farm of W. H. Moore at Rosebank Ontario in April 1915, Buckam Singh at age 22 made his way to the town of Smith Falls, Ontario to enlist with the 59th Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Buckam Singh formally signed his Attestation Papers on April 23, 1915 swearing his allegiance to His Majesty King George the Fifth and assigned his regimental number: 454819. Buckam Singh was then sent to Barriefield Camp near Kingston for his medical examination and training, the 59th Battalion was commanded at this time by Lt.-Col. H.J. Dawson.

Buckam Singh’s name on the Attestation Paper is recorded as ‘Buk Am Singh’ while he signs his name as ‘Bukam Singh’ . He is listed as 5'-7? in height, with a swarthy complexion. It is interesting to note that the form asks for the recruit’s religious denomination, but only includes the following choices – Church of England, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Other Protestants, Roman Catholic or Jewish. Not very accommodating for a Sikh or anyone of another religion which were typically assigned the default of ‘Church of England’ by administrative clerks.

With casualties in Europe mounting from Canadian battles at Neuve Chapelle and the Second Battle of Ypres where the Germans used poison gas, troops in Canada did not have the luxury of extended basic training as it became imperative to get them to Europe as soon as possible. In one 48 hour period at Ypres starting on April 24, 1915 Canadians suffered over 6,000 casualties, one man in every three.

Like many other infantry battalions raised in the early part of 1915 the 59th Battalion sent 2 contingents of about 250 men in the summer and fall of that year, but the main body did not sail until the spring of 1916. Buckam Singh was part of the first contingent that shipped out from the port of Montreal aboard the troop ship S.S. Scandinavian 2 on August 27, 1915. With a top speed of 15 knots, Buckam Singh and his fellow Canadians finally arrived in England one week later on September 5, 1915.

Upon arrival in England most of the new Battalions were absorbed into reserve Battalions. From there troops were sent where they were needed either as reinforcements for the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the army or to the 3rd and 4th Divisions as they were being formed in England. Buckam Singh was therefore transferred to 39th Reserve Battalion awaiting assignment to a combat battalion in need.

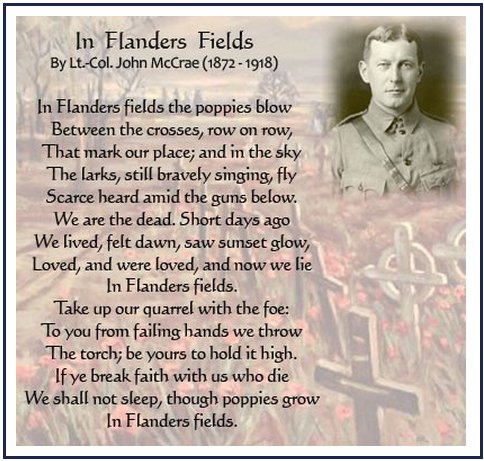

In Flanders Fields

Flanders is a region in Belgium, the name deriving from a medieval state that encompassed parts of what are now Belgium and Northern France. However, the soldiers in the First World War would often refer to their service on the Western Front as “France”, whether it was in France itself or Belgium. The principal town around which the fighting in Flanders revolved was Ypres, and the area around the town of Ypres was also known as the Salient. This region was fought over from October 1914 until practically the end of the war in November 1918.

Flanders is a region in Belgium, the name deriving from a medieval state that encompassed parts of what are now Belgium and Northern France. However, the soldiers in the First World War would often refer to their service on the Western Front as “France”, whether it was in France itself or Belgium. The principal town around which the fighting in Flanders revolved was Ypres, and the area around the town of Ypres was also known as the Salient. This region was fought over from October 1914 until practically the end of the war in November 1918.

Upon his arrival in France on January 21st 1916, Buckam Singh was transferred from the 39th Reserve Battalion to the 20th Battalion. He would remain with the 20th Battalion for the remainder of the war. At the time Buckam Singh joined the 20th Battalion it was assigned to the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division, Canadian Corps and given a section of the front on the Ypres Salient, near Messines. Duty holding the line included: nightly patrolling in no man’s land, endless repairs to wire and trenches, and almost continuous enemy shelling. The winter of 1915-16 was spent in a routine of 18 days on the front and 6 days in the rear, all the while battling lice, trench foot, and disease. In March 1916, steel helmets were issued to all ranks. In the spring of 1916, the Commander of the British Second Army decided that it was essential for an enemy salient near the village of St. Eloi to be eliminated. Following attacks and counter-attacks, the 4th Brigade tried to retake the craters that the 6th Brigade was forced to fall back from. The 20th Battalion managed to retake one crater and held it through a month of concentrated shelling. In one month, the 4th Brigade would suffer 1373 casualties.

Canadian Sikhs were not the only Sikhs in WWI. Sikhs fought in Europe including battles at Flanders (Ypres, La Bassee, St. Julien, Festubert) and Gallipoli as well as in Mesopotamia and Africa during the Great War. At the beginning of the war the Punjab region accounted for 124,000 men in combat ranks as part of the British Indian Army. Three years later, the number had reached a quarter of a million. The Sikhs numbered approximately 65,000 soldiers, or 26% of the Punjabi total, despite representing only 14% of the male population of Punjab of fighting age. Nearly 1,500 distinctions issued for gallantry were awarded to Punjabis, of which 700 went to Sikhs.

Casualty of War

The Battle of Mont Sorrel was a conflict on the southern shoulder of the Ypres Salient, near Sanctuary Wood. The battle was fought between forces of the Canadian Corps, 20th Light Division of the United Kingdom, and the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps of Germany. The battle took place from June 2 to June 14, 1916. German forces were able to initially capture a majority of Mont Sorrel, also known as Hill 62, within the early portion of the battle. However, Canadian forces were eventually able to retake Hill 62, but at a heavy cost, total Canadian casualties for the battle approached 8,000.

With the heavy enemy activity evident from the regimental diary, among one of the combat casualties was Buckam Singh who on June 2, 1916 was hit in the head with shrapnel which his medical report lists as a gunshot wound to the head. He was immediately sent to the No. 8 Stationary Hospital at Wimereux the next day where his wound was dressed and he was then sent to the No. 5 Convalescent Depot at Boulogne to recover from his injury. By the end of the month it was determined that Buckam Singh was sufficiently healthy and on June 29th, 1916 he rejoined the 20th Battalion in the field.

Less than three weeks after rejoining the 20th Battalion Buckam Singh was wounded in combat for a second time. On July 20th, 1916 at St. Eloi he was seriously wounded by a bullet which entered his left knee shattering his leg below the joint. He was immediately sent to No. 3 Canadian General Hospital at Boulogne where his wound was dressed. No. 3 Canadian General Hospital was no ordinary hospital, it was run by none other than one of the most famous Canadians of the war, the soldier, poet and physician Lt. Colonel John McCrae best known for writing the famous war memorial poem ‘In Flanders Fields’.

On July 23, 1916 Buckam Singh was sent from Lt. Colonel John McCrae’s hospital to England to recover from his injuries. He made the voyage across the English Channel aboard the Belgian Hospital Ship Jan Breydel.

Recovery in England

After making the voyage across the English Channel aboard the Belgian Hospital Ship Jan Breydel Buckam Singh would spend quite a bit of time in a series of hospitals and he recovered from his injury. The British government had provided a number of hospitals for use by Canadian troops. These were for the most part for the exclusive use of Canadian patients. Troops from other nations were housed in their own hospitals. Sikhs in the British Indian Army received treatment at the Royal Pavillion in Brighton which the King had converted to a hospital for Indian patients as it’s exterior resembled a oriental palace and might remind the troops of home.

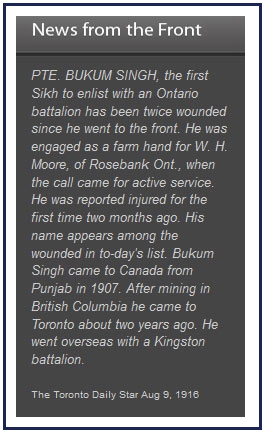

On July 24th 1916 Buckam Singh was admitted to the 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester where he would spend two months recovering from his leg wound. It was during this time that he was interviewed by a newspaper reporter from The Toronto Daily Star and his condition as seriously ill was reported back home in the newspaper of August 9, 1916.

On July 24th 1916 Buckam Singh was admitted to the 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester where he would spend two months recovering from his leg wound. It was during this time that he was interviewed by a newspaper reporter from The Toronto Daily Star and his condition as seriously ill was reported back home in the newspaper of August 9, 1916.

Upon discharge from the Woodcote hospital Buckam was by March 11, 1917 stationed at West Sandling Camp, north of Maidstone, Kent. Here at the Central Ontario Regimental Depot he awaited his eventual transfer back to the front lines in France.

The Last Battle

Just as Buckam Singh was getting ready to return to the battlefields of France and rejoin the 20th Battalion he instead faced the biggest battle of his life from an unexpected enemy.

Following Christmas 1916 Buckam Singh started developing a serious cough which became only worse. The cough only got worst as did his general condition and three months later on March 19th, 1917 he was admitted to the Canadian Military Hospital at Hastings with suspected tuberculosis. Two weeks later on March 28 things had become so serious that Buckam Singh had surgery to remove fluid from his right lung. The following week on March 28 Buckam Singh received the devastating news that the TB tests were positive.

Tuberculosis, or “consumption” as it was commonly known, caused the most widespread public concern in the 19th and early 20th centuries as an endemic disease. In 1918 one in six deaths in France were caused by TB. In the 20th century, tuberculosis killed an estimated 100 million people. The close and cramped army barracks that Buckam Singh spent time in were the perfect deadly environment for TB to spread easily. Unfortunately Buckam Singh contracted the disease before the first general vaccine was invented in 1921. It was not until 1946 with the development of the antibiotic streptomycin that effective treatment and cure became possible. In Buckam Singh’s time the only treatment used for an infected patient was quarantine.

Buckam Singh’s combat days were now over and he would have to fight his battle now on the hospital bed and in isolation. On May 5th he was discharged from the Hastings hospital and preparations were made to return him home along along with other TB patients in quarantine. On May 11, 1917 Buckam Singh made the voyage home across the atlantic aboard the hospital ship HMHS Letitia which docked at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

After arriving at Halifax the gravely ill Buckam Singh made the long train journey to Ontario. He was finally discharged from active service at Guelph Ontario on August 1st, 1918 being judged medically unfit for further war service. He had served a total of 3 years and 100 days on active service. A medical report indicated that he weighed only 127 lbs, had a bulge over his right lung and that his voice was weak and his breath sounded faint with fluid present. The report also noted a shrapnel scar on the right side of the head and a bullet scar through the top of his left leg bone. A medical board recommended at least a further year of treatment at the Freeport Sanatorium Hospital in Kitchener, Ontario.

The Battle Ends

After nearly two and a half years since contracting TB and after having spent over a year in Freeport hospital giving his best fight, Buckam Singh at age 25 finally succumbed to his TB and died on August 27, 1919. This Sikh Canadian hero may have died alone with no family or Sikhs in Ontario but he was buried with honour and respect by the Canadian military in a soldiers grave at Mount Hope Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario where he rests to this day. Private Buckam Singh’s grave is the only known Sikh Canadian WWI soldiers grave in Canada.

After nearly two and a half years since contracting TB and after having spent over a year in Freeport hospital giving his best fight, Buckam Singh at age 25 finally succumbed to his TB and died on August 27, 1919. This Sikh Canadian hero may have died alone with no family or Sikhs in Ontario but he was buried with honour and respect by the Canadian military in a soldiers grave at Mount Hope Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario where he rests to this day. Private Buckam Singh’s grave is the only known Sikh Canadian WWI soldiers grave in Canada.

With the discovery of the Victory Medal of Private Buckam Singh an heroic story of bravery and adventure has been uncovered. Buckam Singh who died alone without his family has once again been reunited and embraced by his family of fellow Sikh Canadians after a separation of nearly a century. HIs story of valour, bravery and sacrifice for his country will now be told and retold and celebrated by generations of Sikh Canadians.

Annual Memorial Services are now conducted at Private Buckam Singhs grave.

Material Courtesy & For more information visit the online exhibit at www.SikhMuseum.com

Courage

Letter from Pvt. Waryam Singh, 38th Battalion (Eastern Ontario Regiment) Canadian Expeditionary Force, Nov 1916, France, later wounded Apr 1917.

“Shells and bullets were falling like rain and one’s body trembled to see what was going on. But when the order came to advance and take the enemy’s trench, it was wonderful how we all forgot the danger and were filled with extraordinary resolution. We went over like men walking in a procession at a fair, and shouting, we seized the trench and took the enemy prisoner."

Buckam Singh’s name was spelled in a variety of ways during his lifetime :

1) Buk Am Singh – Attestation papers

2) Bukam Singh – Signature on attestation

3) Buckm S. – Medical report

4) Bukum Singh – Toronto Daily Star

5) Buckam Singh – Signature on discharge

6) Bukkan Singh – Gravestone

7) B. A. Singh – Victory medal

For the sake of consistency the spelling he used in his last known signature, Buckam Singh has been used.