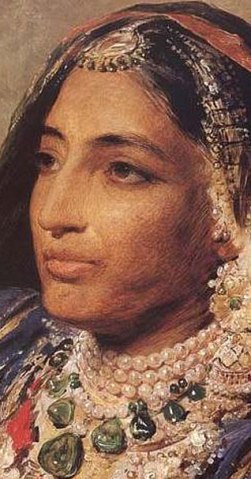

Punjab’s women have always been considered among the most beautiful in the land. During the Mughal days, they were sought after by the kings and nobles to embellish their harems. There was Anarkali who became a legend as she allured Prince Salim with her grace and charm and even led him to stage a revolt against his father, the Emperor Akbar. Salim on ascending the throne as Jahangir built a mausoleum for Anarkali in Lahore and the famous bazaar of the city is named after her. Rana-Dil was another Punjabi beauty who enchanted Dara-Shikoh and Emperor Shahjahan allowed him to marry her and she was granted the same privileges and honour as other princesses. During the later Mughal period, we come across Lal Kunwar, a performing artiste, whose glamour and charm became part of folklore. Her adventurous romance with Emperor Jahandar Shah, the grandson of Aurangzeb, elevated her to the status of a queen with the title of Imtiaz Mahal and she came to be known as the "Singing Empress". During the Sikh Empire, there was a young Muslim beauty called Moran who enchanted the ‘Lion of Punjab’ -- Maharaja Ranjit Singh -- and became his favourite mistress. Then we had Maharani Jind Kaur -- Rani Jindan -- the youngest wife of the Maharaja, famous for her attractive looks and domineering personality. The surviving portraits of her bear testimony to her loveliness and eye appeal. According to Sir Herbert Edwardes, "she had more wit and daring than any man of her nation". The institution of zenana and the purdah custom had come into vogue with the advent of Muslim rule and it continued until the beginning of the twentieth century. Punjab came under the British rule in 1849. By that time the racial gulf between the ruler and the ruled was firmly established. While till the early decades of the 19th century, it was quite common for the British civilians and soldiers to have native women as their bibis or unofficial wives, this practice came to be frowned upon and had virtually vanished by the time the British came to Punjab. Some European generals employed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh had married Punjabi women. There is a fascinating painting, portraying General Jean-Francois Allard and his Punjabi wife, children and female servants, done by a local artist at Lahore in 1838. This painting represents a challenge to the British colonial culture in India. Sir Charles Metcalfe, one of the most distinguished and talented civilian of the East India Company, lived with a Punjabi lady he had met during a diplomatic mission to Ranjit Singh’s court in 1809. His romantic and unorthodox liaison with this Punjabi woman was then a common topic of gossip but Metcalfe made no secret of it nor about his three sons from her. As a great patron of the performing arts, the ‘Lion of Punjab’ maintained a troupe of 150 beautiful dancing girls and entertained his guests with gorgeous nautch parties. W.G. Osborne, who accompanied Governor-General Auckland to Ranjit Singh’s court at Lahore, recalls in his journal an interesting conversation with the Maharaja about these beautiful women. "How do you like them", asked Ranjit Singh, "Are they handsomer than the women of Hindostan? Are they as handsome as English women?" Osborne replied that he admired them all very much and named the two he thought were the handsomest. Emily Eden, the sister of Auckland who also accompanied him to Lahore, was invited to meet the Ranis. She was struck by their beauty and grace and wrote that "Four of them were very handsome. Two would have been beautiful anywhere". Maharaja Sher Singh’s wife is also described as really beautiful, "very little, very fair with enormous black eyes, and a pretty, clever expression". Henry Stenbach a German soldier with the Maharaja pays a glowing tribute to the valour, daring and fortitude of the Hindu ranis of Ranjit Singh as they performed sati on his death. In his vivid description of the event, he wrote: "His four queens dressed in their most sumptuous apparel, then followed, each in a separate gilt chair ... Before each of the queens was carried a large mirror, and gilt parasol, the emblems of their rank ...To the last moment of this terrible sacrifice, the queens exhibited the most perfect equanimity; far from evincing any dread of the terrible death which awaited them, they appeared in a high state of excitement and ascended the funeral pyre with alacrity". Until the middle of the 18 century, there was practically no visual record of the people of the subcontinent based on first hand observation. The British artists who began arriving from 1760 onwards mostly applied their talent to landscape painting, portraits of the ruling elite and princes or historical events of imperial interest. But there were some, both professional and amateur, who were inspired by the exotic people of the various kingdoms, especially native women. These artists have left behind some paintings and drawings of native women of different classes. There were also local artists patronised by the British. They imbibed some of the western techniques and adapted their painting style to meet the taste of their patrons. There is an enormous collection of their drawings in different museums and galleries around the world and these are defined as ‘Company school’ paintings. The British officials and travellers employed local artists at Lahore and Amritsar to make drawings for them depicting famous monuments of Punjab and also the local people. Punjabi women, however, hardly figure in this collection. Among the notable British artists who visited Punjab in the 19th century and have left behind valuable collection of their paintings and drawings were G.T. Vigne, A.F.P. Harcourt, H.A. Oldfield, C.S. Hadinge, and William Carpenter. Their works chiefly depict Punjab’s picturesque landscape, historical monuments etc. Even Emily Eden, an accomplished artist who had access to the royal zenana, did not portray any Punjabi ladies in her monumental work, ‘Portraits of the Princes and people of India’ which include magnificent paintings of Ranjit Singh, his sons and other Sikh personalities. Some artists did succeed in making sketches of women of the Punjab hills who were neither shy nor followed the purdah custom. The Punjabi women of the plains observed strict purdah and would not expose themselves to any male artists, whether foreign or native. There are practically no true-to-life pictures of Punjabi women of the upper classes. There is one by a local artist of Maharani Jindan who had come out of the veil to become the regent of Duleep Singh. The only women who readily agreed to pose for artists were public entertainers and dancing girls, and those belonging to lower working classes in exchange for monetary reward. At times, the artists were able to sketch village women as the rural purdah custom was not prevalent in rural areas. It is observed that Punjabi women were particularly fond of jewellery. A variety of ornaments made by highly skilled craftsmen were worn from head to toe. Emily Eden describes in her journal the gorgeous costumes and ornaments worn by the royal ladies at Lahore. She wrote: "Their heads look too large from the quantity of pearls with which they load them and their nose-rings conceal all the lower part of the face and hang down almost to the waist. First, a crescent of diamond comes from the nose and to that is hung a string of pearls and tassels of pearls and rings of pearls with emerald drops". Their dress consisted of silver gauze veils, tinselly tunics and very tight trousers. After the advent of the camera, commercial photography rapidly replaced painting by professional portrait artists. Here again, when it came to Punjabi women, they did not want to face the camera wielded by a man. It is only after the spread of education and emancipation of Indian women in the 20th century that the old taboos of purdah and seclusion were slowly discarded. I still recall that considering the market potential in this field, an enterprising Punjabi lady in Lahore set up a special photo studio for women, sometime in the late 1930s. The romanticised image of Punjabi women has been vividly captured in the folklore and love legends of Punjab like Heer Ranjha, Sohni Mahiwal, Mirza Sahiban, Sehti Murad, Balo-Mayia, etc. The Punjabi woman has been extolled for her extraordinary beauty, grace and seductive charm. Poets and bards have used superlative terms to describe her fair and wheatish complexion with her rosy cheeks. Others have sung praises of her chiselled features and robust health. That reminds me of an old Punjabi lyric, ‘shishey nu(n) tarrerh pai gayi / wal wondi ne dhyan jadon marya’ (The force of her gaze drove a crack in the mirror as she looked at it while combing her hair.) A mid-nineteenth century folk song portrays a young maiden from the Majha region of Punjab thus: majhe di mastani jatti / Amarsar navan chali / Amarsar jaiyai te ki / kuj liahiye / mauli, dandasa, kangi patti / patti oh maaye -- / majhe di mastani jatti The romantic expressions used by young lovers contain the most extraordinary similes. The lover is addressed as ‘chann’, i.e. the moon, or sona and the beloved is soni, i.e. the beautiful or the gilded one. Some ardent lovers use the simile of a rose bud as in the following couplet: sun kurriye Punjab diye, / dukh tainu kis gal da hai soniye / sun kaliye gulab diye Another noteworthy point is that the lover treats the beloved and vice versa as equal partners in the game of love as is evident from the expression of calling each other ‘haani’, meaning companion or partner. The women’s costume, both in the rural and urban Punjab, has been Suthan Jhaga or Shalwar-Kameez for over a century. In spite of various changes in fashion, this attire has not only survived but has now been universally adopted by Indian women of all age-groups throughout the country. The chunni or the head cover, which goes along with the dress, is the most graceful part of the costume. The Punjabi women were particularly known to be fastidious about their personal appearance. They used traditional cosmetics and beauty aids for their hair, eyelids, eyebrows, teeth, lips and hands. For their face, they used a kind of pomade made of orange peels ground fine upon a stone and mixed with besan or a paste of wheat flour mixed with butter, cream and ghee. The use of kaajal beautified their eyes. We have an amusing couplet about it: ‘kinwain pavan main akhian ch kajala, ke akhian ch tu wasda’. (How can I put kaajal in my eyes because you are residing there?) |