Mandip Kaur, a 29-year-old housewife from a farming family in southern Punjab, guards her husband round the clock.

"I fear he may commit suicide," she says in broken Hindi.

Almost every village in Punjab has witnessed a suicide in their once-prosperous farming families and it is a major issue in the general election.

Ms Kaur's 35-year-old husband, Lakhbir Singh, a small farmer with a two-acre land holding, is a strong and neatly dressed man.

He shows no sign of irritation or discomfort when we meet him in the village of Boparai Khurd in Barnala, about 500km (300 miles) north of Delhi.

Each year before the harvest, the small farmers of Punjab, who make up nearly 85% of the state's farming community, borrow from local rural moneylenders at exorbitant interest rates to meet production costs, including fertilisers and electricity for irrigation.

"[Lakhbir] has a loan of more than 700,000 rupees ($15,000), which he cannot repay," says Ms Kaur.

"[Lakhbir] has a loan of more than 700,000 rupees ($15,000), which he cannot repay," says Ms Kaur.

Defaulting on payment increases the rates of interest and a farmer is publicly humiliated in the local panchayat (self-governing rural body) if he fails to pay up.

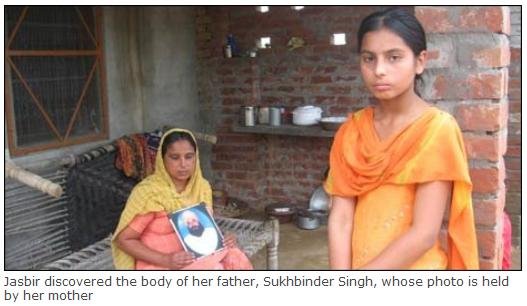

"His elder brother, my father, committed suicide more than a year ago, as his loan had accumulated up to $20,000," says 15-year-old Jasbir, who discovered her father's body.

"I do not think I can ever repay the whole amount," Lakhbir confesses.

The Bhartiya Kisan Union-Ekta, (BKU-United), one of the largest farmers' unions in Punjab, is urging its members not to vote in the election if they feel that none of the parties is addressing their needs.

'Major issue'

National Crime Records Bureau statistics say close to 200,000 farmers have committed suicide in India since 1997.

The Punjab government says the state produces nearly two-thirds of the grain in India.

But the state has faced many economic crises since the the mid-1990s.

No comprehensive official figures on farmer suicides in the area are available.

But a report commissioned by the government of Punjab this week estimated that there had been "close to 3,000 suicides" among farmers and farm labourers in just two of Punjab's 20 districts in recent years, agriculture ministry sources told the BBC.

But a report commissioned by the government of Punjab this week estimated that there had been "close to 3,000 suicides" among farmers and farm labourers in just two of Punjab's 20 districts in recent years, agriculture ministry sources told the BBC.

The general secretary of BKU-United, Sukhdev Singh Khokri, says: "The findings of this report will snowball into a major electoral issue."

Another government report published in 2007 suggested that "about 12% of marginal and small farmers have left farming" over the past few years.

Among the reasons is the lack of access to credit, a facility denied by banks to farmers with no property.

"Bank loans to small farmers without collateral declined sharply as India introduced neo-liberal policies in the 1990s," says Bernard D'Mello, deputy editor of Economic and Political Weekly.

Farmers had to approach rural moneylenders who charge exorbitant rates.

Amarjit Singh, another small farmer from Barnala whose father committed suicide a few years back, says: "My father could not read or write, so he could not calculate the amount of loan he had incurred.

"Once it reached a staggering sum, he was publicly threatened by the moneylender and committed suicide.

"If I am asked to pay my father's debt, I will also have to commit suicide," says Amarjit, who has also taken on loans to meet rising production costs.

Surplus

The Punjab government's website proclaims that "India has gone from a food-deficit to a food-surplus country" largely because of the Green Revolution of Punjab.

In the 1960s, it revolutionised agricultural production by introducing high-yield varieties of seeds, chemical fertilisers, insecticides and machinery.

In the 1960s, it revolutionised agricultural production by introducing high-yield varieties of seeds, chemical fertilisers, insecticides and machinery.

But the 2007 report criticises the revolution and its surplus of crops.

Independent researcher and activist Ranjana Padhi says: "Since everyone had money, labourers were replaced by tractors and unemployment increased, while productivity steadily declined."

As production costs have risen, food prices have slumped.

Traditionally, the government buys grain from farmers and distributes it in the open market.

Sukhpal Singh, a senior economist at Punjab Agricultural University, feels farmers had to bear government prices that were too low and failed to take into account "risk factors like crop failure or soil maintenance".

Poor prices internationally restricted the government from a higher buying rate for farmers.

Another factor is the subsidies in place in areas such as Europe.

Another factor is the subsidies in place in areas such as Europe.

German non-governmental organisation Foodwatch says the European subsidies are responsible for large-scale unemployment and poverty among farmers in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The issue is pending with the World Trade Organisation but talks on the issue have repeatedly failed.

Bernard D'Mello feels the worst is yet to come given the recent recession.

"Commodity prices are plummeting in the international market as a result of recession, which will depress the price in Indian markets as well and farmer suicides may increase in coming months," he says.

Punjab Agriculture Minister Sucha Singh Langah says the state government has increased farming subsidies to all categories in recent years.

But the Election Commission has put further projects on hold pending the polls.

Meanwhile the farmers' unions are co-ordinating a joint protest to highlight the plight of farmers.

Amarjit Singh will be one taking part. "We will stop everything in the state for two days," he says.