The Making of 'The Protester' Portfolio

By TIME Staff

History often emerges only in retrospect. Events become significant only when looked back on. No one could have known that when a Tunisian fruit vendor set himself on fire in a public square in a town barely on a map, he would spark protests that would bring down dictators in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya and rattle regimes in Syria, Yemen and Bahrain. Or that that spirit of dissent would spur Mexicans to rise up against the terror of drug cartels, Greeks to march against unaccountable leaders, Americans to occupy public spaces to protest income inequality, and Russians to marshal themselves against a corrupt autocracy.Protests have now occurred in countries whose populations total at least 3 billion people, and the word protest has appeared in newspapers and online exponentially more this past year than at any other time in history.

Is there a global tipping point for frustration? Everywhere, it seems, people said they'd had enough. They dissented; they demanded; they did not despair, even when the answers came back in a cloud of tear gas or a hail of bullets. They literally embodied the idea that individual action can bring collective, colossal change. And although it was understood differently in different places, the idea of democracy was present in every gathering. The root of the word democracy is demos, "the people," and the meaning of democracy is "the people rule." And they did, if not at the ballot box, then in the streets. America is a nation conceived in protest, and protest is in some ways the source code for democracy — and evidence of the lack of it.

The protests have marked the rise of a new generation. In Egypt 60% of the population is under the age of 25. Technology mattered, but this was not a technological revolution. Social networks did not cause these movements, but they kept them alive and connected. Technology allowed us to watch, and it spread the virus of protest, but this was not a wired revolution; it was a human one, of hearts and minds, the oldest technology of all.

Everywhere this year, people have complained about the failure of traditional leadership and the fecklessness of institutions. Politicians cannot look beyond the next election, and they refuse to make hard choices. That's one reason we did not select an individual this year. But leadership has come from the bottom of the pyramid, not the top. For capturing and highlighting a global sense of restless promise, for upending governments and conventional wisdom, for combining the oldest of techniques with the newest of technologies to shine a light on human dignity and, finally, for steering the planet on a more democratic though sometimes more dangerous path for the 21st century, the Protester is TIME's 2011 Person of the Year.

http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2101745_2102139,00.html

------------------------------------

TIME Person of the Year Award

The Protester

By KURT ANDERSEN

|

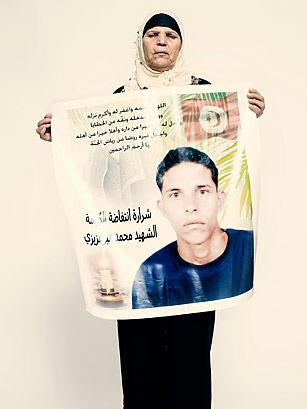

| "Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia PHOTOGRAPH BY PETER HAPAK FOR TIME |

Once upon a time, when major news events were chronicled strictly by professionals and printed on paper or transmitted through the air by the few for the masses, protesters were prime makers of history. Back then, when citizen multitudes took to the streets without weapons to declare themselves opposed, it was the very definition of news — vivid, important, often consequential. In the 1960s in America they marched for civil rights and against the Vietnam War; in the '70s, they rose up in Iran and Portugal; in the '80s, they spoke out against nuclear weapons in the U.S. and Europe, against Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, against communist tyranny in Tiananmen Square and Eastern Europe. Protest was the natural continuation of politics by other means.

And then came the End of History, summed up by Francis Fukuyama's influential 1989 essay declaring that mankind had arrived at the "end point of ... ideological evolution" in globally triumphant "Western liberalism." The two decades beginning in 1991 witnessed the greatest rise in living standards that the world has ever known. Credit was easy, complacency and apathy were rife, and street protests looked like pointless emotional sideshows — obsolete, quaint, the equivalent of cavalry to mid-20th-century war. The rare large demonstrations in the rich world seemed ineffectual and irrelevant. (See the Battle of Seattle, 1999.)

There were a few exceptions, like the protests that, along with sanctions, helped end apartheid in South Africa in 1994. But for young people, radical critiques and protests against the system were mostly confined to pop-culture fantasy: "Fight the Power" was a song on a platinum-selling album, Rage Against the Machine was a platinum-selling band, and the beloved brave rebels fighting the all-encompassing global oppressors were just a bunch of characters in The Matrix. (See pictures of protesters around the world.)

"Massive and effective street protest" was a global oxymoron until — suddenly, shockingly — starting exactly a year ago, it became the defining trope of our times. And the protester once again became a maker of history.

Prelude to the Revolutions

It began in Tunisia, where the dictator's power grabbing and high living crossed a line of shamelessness, and a commonplace bit of government callousness against an ordinary citizen — a 26-year-old street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi — became the final straw. Bouazizi lived in the charmless Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, 125 miles south of Tunis. On a Friday morning almost exactly a year ago, he set out for work, selling produce from a cart. Police had hassled Bouazizi routinely for years, his family says, fining him, making him jump through bureaucratic hoops. On Dec. 17, 2010, a cop started giving him grief yet again. She confiscated his scale and allegedly slapped him. He walked straight to the provincial-capital building to complain and got no response. At the gate, he drenched himself in paint thinner and lit a match.

(See pictures of Sidi Bouzid)

"My son set himself on fire for dignity," Mannoubia Bouazizi told me when I visited her.

"In Tunisia," added her 16-year-old daughter Basma, "dignity is more important than bread."

In Egypt the incitements were a preposterously fraudulent 2010 national election and, as in Tunisia, a not uncommon act of unforgivable brutality by security agents. In the U.S., three acute and overlapping money crises — tanked economy, systemic financial recklessness, gigantic public debt — along with ongoing revelations of double dealing by banks, new state laws making certain public-employee-union demands illegal and the refusal of Congress to consider even slightly higher taxes on the very highest incomes mobilized Occupy Wall Street and its millions of supporters. In Russia it was the realization that another six (or 12) years of Vladimir Putin might not lead to greater prosperity and democratic normality.

In Sidi Bouzid and Tunis, in Alexandria and Cairo; in Arab cities and towns across the 6,000 miles from the Persian Gulf to the Atlantic Ocean; in Madrid and Athens and London and Tel Aviv; in Mexico and India and Chile, where citizens mobilized against crime and corruption; in New York and Moscow and dozens of other U.S. and Russian cities, the loathing and anger at governments and their cronies became uncontainable and fed on itself.

The stakes are very different in different places. In North America and most of Europe, there are no dictators, and dissidents don't get tortured. Any day that Tunisians, Egyptians or Syrians occupy streets and squares, they know that some of them might be beaten or shot, not just pepper-sprayed or flex-cuffed. The protesters in the Middle East and North Africa are literally dying to get political systems that roughly resemble the ones that seem intolerably undemocratic to protesters in Madrid, Athens, London and New York City. "I think other parts of the world," says Frank Castro, 53, a Teamster who drives a cement mixer for a living and helped occupy Oakland, Calif., "have more balls than we do."

In Egypt and Tunisia, I talked with revolutionaries who were M.B.A.s, physicians and filmmakers as well as the young daughters of a provincial olive picker and a supergeeky 29-year-old Muslim Brotherhood member carrying a Tigger notebook. The Occupy movement in the U.S. was set in motion by a couple of magazine editors — a 69-year-old Canadian, a 29-year-old African American — and a 50-year-old anthropologist, but airline pilots and grandmas and shop clerks and dishwashers have been part of the throngs.

http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2101745_2102132,00.html

------------------------------------------

A Year in the Making

By Richard Stengel

|

| Andersen and Stengel in Cairo's Tahrir Square |

The 2011 Person of the Year issue is the product of a year's worth of reporting and thinking. From the beginning of the Arab Spring, we dedicated an abundance of resources to this world-historical story. We also watched as the germ of protest spread to Europe and then America and now Russia. Last month, Kurt Andersen and I took a trip to Egypt and Tunisia to trace this spirit of revolution to its roots. Kurt, one of America's finest essayists and novelists, wrote the sweeping piece that explains the links and the larger meaning among the protests in dozens of countries.  We were accompanied on that trip by deputy international editor Bobby Ghosh, Cairo correspondent Abby Hauslohner and reporter Rania Abouzeid, who is based in Lebanon. Bobby, Abby and Rania have spent many months reporting on the Arab Spring, with all their stories coordinated by our stalwart news director, Howard Chua-Eoan. For this issue, TIME contract photographer Peter Hapak and international photo editor Patrick Witty traveled nearly 25,000 miles and photographed protesters from eight countries. The stunning portfolio brings together the faces of Occupy Wall Street and Oakland, Calif.; los indignados of Spain; the young men and women of Egypt, Tunisia and Greece; a crusader against corruption in India; a state-government protester in Wisconsin; and a Tea Party activist in New York City. You can see more of the images on lightbox.time.com.

We were accompanied on that trip by deputy international editor Bobby Ghosh, Cairo correspondent Abby Hauslohner and reporter Rania Abouzeid, who is based in Lebanon. Bobby, Abby and Rania have spent many months reporting on the Arab Spring, with all their stories coordinated by our stalwart news director, Howard Chua-Eoan. For this issue, TIME contract photographer Peter Hapak and international photo editor Patrick Witty traveled nearly 25,000 miles and photographed protesters from eight countries. The stunning portfolio brings together the faces of Occupy Wall Street and Oakland, Calif.; los indignados of Spain; the young men and women of Egypt, Tunisia and Greece; a crusader against corruption in India; a state-government protester in Wisconsin; and a Tea Party activist in New York City. You can see more of the images on lightbox.time.com.

For our runners-up, London bureau chief Catherine Mayer chatted with Kate Middleton, editor-at-large David Von Drehle caught up with budgetmaster Paul Ryan, and contributor Bart Gellman tracked down Admiral William McRaven, who led the mission that brought down Osama bin Laden. We couldn't think of a better photographer to shoot Ai Weiwei than the artist himself, who also created a piece of art for us symbolizing the year of the protester. Representative Gabby Giffords, whose recovery from a devastating gunshot wound in January is chronicled in her new book, answered questions via e-mail about her remarkable year.

This marvelous issue was edited by executive editor Radhika Jones, who also edited last year's Person of the Year issue. Deputy art director Chrissy Dunleavy is responsible for the issue's elegant design, and graphic artist Shepard Fairey created our striking cover image from a composite of 26 protest images.

http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2101745_2102141,00.html