Book Review

May 13, 2014

REVIEW By

Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed

|

|

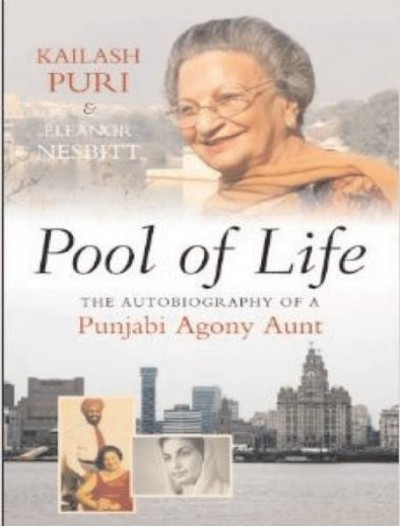

Pool of Life: The Autobiography of a Punjabi Agony Aunt |

|

About the author (2013) Kailash Puri is an author, a poet, an advice columnist, and a sexologist. She is the author of The Myth of UK Integration. Eleanor Nesbitt is professor emeritus in religions and education at the University of Warwick and a founding member of Punjab Research Group. She is the author of several books, including Intercultural Education: Ethnographic and Religious Approaches and Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. |

It all started in and around Rawalpindi

It has been a sheer pleasure to read the autobiography of Kailash Puri, written largely in Punjabi and rendered into very readable English by Professor Emeritus Eleanor Nesbitt. We learn that Kailash was born in Arya Mohalla, Rawalpindi, just next to Gordon College. Being the fifth daughter in a family of Khatri Sikhs who longed for a son, her parents ironically named her Veerawali (sister of brothers)! She adopted her penname, Kailash, later in life when she began writing. The Puris, like millions of other refugees, had to run for their lives at the time of partition in 1947 and to begin life again from scratch in India. It so happens that one of my current students at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) Nimra Zulfiqar’s family shifted to Arya Mohalla from Ludhiana and Jullundur in 1947. So, the partition saga continues to bring forth strange coincidences, connections and associations.

Although born in Rawalpindi, Kailash always felt that her roots were in the ancestral village of Kallar (now called Kallar Syedan) some 25 miles from the city. I visited Kallar in December 2004 for fieldwork on my Punjab book. In 1947, it escaped largely unscathed raids by Muslim mobs because the Sikhs and Hindus could find refuge in the large fortress-like building of the direct descendants of Guru Nanak, the Babas or Bedis. However, the Sikh and Hindu inhabitants of the nearby village of Thamali were almost wiped out.

Chapters one to five tell the story of the first phase of her life. Her father, Sohan Singh Puri, was a businessman. He built a home in Lahore as well and so the family stayed in both Rawalpindi and in Dharampura, Lahore. Like Parkash Tandon’s Punjabi Century, the portrayal of the social and cultural life of the old Punjab is done with great skill and absolute honesty. Although a believing Sikh, she deftly lays bare the dead weight of traditional life permeated by superstitions. A Puri boy, Gopal, a talented scientist, saw her, found her pretty and wanted to marry her. It was a proposal that contravened the rules of consanguinity applicable to Hindu and Sikh marriage because Kailash and Gopal belonged to the same ‘Puri Gotra’ (clan) within the Khatri caste. Intrigues and jealousies came into play and typically a villain reminiscent of Kado Langa of Heer fame, a close relative, Sunder Singh, tried his best to subvert the match but Gopal’s resolve prevailed and her parents agreed to the marriage.

Gopal Singh Puri secured a scholarship to do a second PhD in London in 1945 (presumably after the war). Kailash joined him later. They lived on a tight budget in a small room in very austere conditions but the English landlord and landlady proved to be extremely kind and considerate. Also, the shopkeepers and other English people they met were courteous and sympathetic. Their first child, Shaminder, was born in London in October 1947. Later, two girls Kiren (1950) and Risham (1956) were also born.

The Puris returned to India in 1948. Kailash’s parents had settled in Dehra Dun, where after some struggle Gopal found a job as forest ecologist and technical secretary to the Indian Council of Ecological Research at Dehra Dun. Intrigues and plots hatched by jealous colleagues and superiors made life difficult. When an opportunity arose, Gopal accepted a posting in Pune, Maharashtra. Here Kailash began her writing career — first as a columnist on cookery. Encouraged by Gurbaksh Singh, the editor of Preetlari (once a favourite of pre-partition Punjab leftists), she launched the first Punjabi language magazine for women.

The family went to Africa in 1961 where Gopal taught at Nigerian and Ghanian universities. The author once again impresses the reader with vivid and frank depictions of political, social and cultural life in West Africa. The presentations are done with sympathy and genuine curiosity to learn and understand. We learn that African women are quite enterprising and even those from the elite try to make an income by selling petty goods.

The last part of the book tells the story of the Puris arriving in the UK around 1966. An uphill task of finding work in a very different UK begins. By that time, thousands of people from the Indian subcontinent, mostly Punjabi Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus, were already there. The culture clashes and shocks experienced by the host society and the immigrants had replaced the friendly attitude that Kailash experienced on her first stay in that country. Even with all his outstanding qualifications, Gopal had great difficulty in finding a job. Kailesh also had to struggle hard but got a break in Southall but then the family moved to Liverpool where they have been settled since.

However, all along, even in the most adverse circumstances, she continued writing and expanding the ambit of her expertise from cookery to family affairs, sexual relations and other related problems. She calls herself an ‘agony aunt’ and that is a very appropriate description. People consulted her on all the typical problems that ensue once the cultural framework of the home country is no longer applicable and traditional life can no longer be reproduced as before. That she achieved such authority and status without any formal university education speaks a lot for her native intelligence and ability to learn and develop.

The most touching chapter is the one on Kailash and Gopal’s visit to Pakistan. It confirms an urge all Punjabis uprooted from their roots have felt — to revisit, at least once, their roots. Finally, in 1983, an old world, long abandoned but never forgotten came back to life. The home at Dharampura was in ruins but both in Arya Mohalla and especially in Kallar the old buildings were still there and of course they met people who remembered their families. They were offered hospitality by those who lived in their old homes.

Kailash Puri’s autobiography is a must read for those trying to make sense of physical migrations and concomitant social and intellectual transformations that have wrought the lives of Punjabis from the 1940s onwards.