|

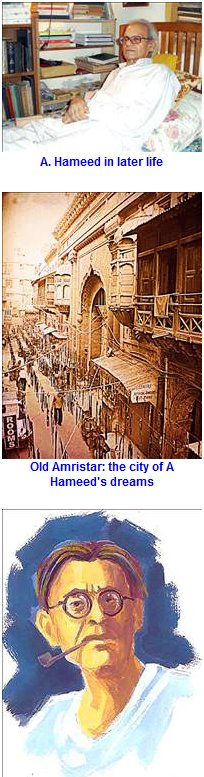

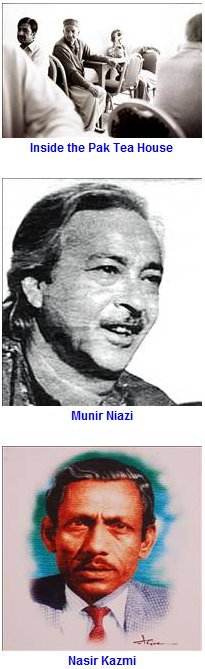

A partitioned man recalls the romantic and the writer that was A. Hameed Intizar Hussain in his paper had declared him one of the three romantic writers in Urdu produced by the 20th century; the other two being Nasir Kazmi and Munir Niazi. I imagine all three sipping tea in the Pak Tea House of Paradise and joking. The decorations in our four-storied home in Delhi Gate included framed pictures of famous Muslim shrines in Lahore, Pakpattan, Ajmer, Delhi, Baghdad and Najfhung neatly in a reception room next to the marble mausoleum built by my grandfather for himself and his wife. When I was able to read I discovered that the pictures were published and marketed by a local company called Hafiz Qamar Din & Sons. The name of the publisher appeared on the bottom of pictures popularly known as Qitaat. I never pondered who Hafiz Qamar Din was until I befriended A. Hameed (Hamid). He was Hameed’s father-in-law whose talented daughter, Rehana, had successfully replaced Rajida, the fictional heroine of his first short story – Manzil Manzil. A. Hameed called her Hafeeza. She was on his bedside in Jinnah Hospital when he breathed his last late April. After a memorial meeting held in the Washington Area, a woman of Rehana’s age who runs a home décor business approached me and bashfully acknowledged that college girls of her time used to hide A. Hameed’s romantic writings under their pillows and read them in seclusion. Rehana was obviously one of them. Hameed and Rehana got married and moved to a large house built by Hafiz Qamar Din on Fleming Road behind the Lahore Hotel. Once I accompanied Hameed to his home after midnight and found Rehana waiting for her beloved husband. She offered us spicy meatballs she had cooked for him that evening. I tried to complain about the excessive dose of chilies in the food and Hameed stopped me by putting his hand on my mouth. Many years later, in 1982, when he came to Washington to work for VOA, I again raised the old matter by invoking my First Amendment rights. He told me that my complaint is time-barred because they had drastically reduced spices in their food, already. Sajjad Haider Yildram could be called the first romantic writer of the Urdu language but he was inspired by the romantic movement in English literature. Hameed liked the romanticism of Krishan Chandar but carved his own way in literature when he held his pen. Saadat Hasan Manto read his first short story and said, “ A. Hameed is a barker (Bakwasi) who gets romantic even after looking at an electricity pole.” A. Hameed valued the comment of the master storyteller of his age so much that he copied the opinion on the flap of his next book. During one of our last conversations over the telephone he reported the proceedings of a literary meeting held in his honor at Alhamra by Attaul Haq Qasmi. Intizar Hussain in his paper had declared him one of the three romantic writers in Urdu produced by the 20th century; the other two being Nasir Kazmi and Munir Niazi. I imagine that all three are sipping tea in the Pak Tea House of Paradise and joking. Hamid Akhtar had also talked about the life and art of A. Hameed but the latter did not convey his views to me. Included in his paper were stories of his stay in Washington as he heard them from me. Khalid Hasan introduced A. Hameed to English readers (he did this after translating many a verse by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and short stories by Manto). He initiated translations of Hameed’s essays but soon got lost. Translation of literature is important but hazardous. He abridged many of his pieces since they needed editing. This caused some tension between author and translator. I had assumed the role of a firefighter. However a dispatch from Khalid which appeared in TFT of July 2004 spoke highly of Hameed’s reminiscences of Lahore. In ‘ A. Hamid’s Lahore’ , Khalid said that “he writes about the city and he writes about his friends and those he came across in a long career devoted to writing, both serious and journalistic. To have lived by what you write is in itself remarkable in a society where writers receive little respect, and even less money.” In 1989 when I visited him at his home in Samanabad and asked him how he was doing after returning from the United States, he told me, “I have learnt to work eight hours a day. I go to the writing table for four hours. Take a lunch break. Lie down for a while and then return to my desk for another four hours of work.” The prolific A. Hameed was one of the few Urdu writers who earned their livelihood through writing. Khalid said A. Hameed has written millions of words – in travelogues, novels, short stories, children’s books, detective fiction and more. To this list you can also add scripts for radio and television programs. Many of his fans perhaps did not know that A. Hameed was a born broadcaster. He ran to Rangoon to see his sister and her husband who worked for the propaganda wing of the war effort. Hameed volunteered for radio and broadcast to Punjabi soldiers in the Indian Army. At Radio Pakistan, Lahore, he worked as a staff artist in the company of luminaries like Shaukat Thanvi, Sufi Tabassum, Mirza Adeeb and Nasir Kazmi. Contrary to his temperament, he was elected president of the staff artists union: its general secretary being Abul Hassan Naghmi, my neighbor in Lahore and here in the United States. Radio staff artists made little more money than “producers” but got no fringe benefits, not to speak of a pension. Americans did not or could not perceive that a great Urdu writer had travelled to Washington to work for them. The contract could be extended beyond the first two years but it expired and he returned home with his wife and two children happily. A. Hameed was born in Amritsar circa 1928 but gained his adulthood in Lahore. He did not distinguish one city from the other. He loved both. Until Partition they were twin cities hardly 30 miles apart. A train ran between the two ferrying workers from one side to the other. Hameed took this Babu Train to Lahore often without a ticket and enjoyed breaking the law. About his birthplace he wrote: “For me Amritsar is my lost Jerusalem and I am its wailing wall. I do not remember anything about Amritsar. Remembers he who forgets. Amritsar circulates in my blood. I go to sleep after looking at Amritsar and the first thing I see it after waking up in the morning. When I walk the Company Bagh accompanies me. When I sit the Secretary Bagh’s trees provide me with a shadow. When I speak I can hear the calls to prayers from Amritsar mosques. When I am quiet water from Amritsar canals passes by me, whispering. I look at one of my hands and find streets of my neighborhood sleeping on it. I look at the other hand and see all the flowers, trees and spring breezes sitting on it, smiling. An Amritsar-bound friend asked me recently what he should bring for me. I told him to get me a flower from the Company Bagh.” After the Partition of the subcontinent, he along with his family moved to Lahore where the queen of his romantic thoughts lived. In “First Day in Pakistan” he describes his migration without the age-old prejudices that caused it. “On the deserted and fire-stricken morning of August 14, 1947, we said goodbye for good to Amritsar and boarded the Lahore-bound Howrah Express….People of Lahore were serving dal and roti to refugees on every platform of the railway station…..Do not go through the overhead bridge, Sikhs are firing from Gurdwara Shaheed Gunj, the volunteers warned us. We were surprised that Lahorites could not expel Sikhs from here…. a speeding wagon filled with scared Hindu and Sikh women and children took a turn to Empress Road. In the meantime, a young and handsome Sikh donning a dark brown turban appeared from nowhere. His death had drawn him there. As he neared our camp, a boy picked up a double brick from the ground and hurled it toward one of his temples. An attaché case he was carrying fell down and its contents scattered on the road. They included red glass bangles he had perhaps brought from Ludhiana, Jullundhar, Patiala or Hoshiarpore for his sister, fiancé, sister-in-law or wife as a gift….We stayed in Wassanpora for a few days and then moved to an evacuee house in Faiz Bagh. Its upper story had been allotted to us. When it rained during the nights, the roof seeped. We would place empty utensils at various places and spend the night listening to the music (jaltrang ) of the rain drops. After the day break, we would find slush all over in the streets. No one had found a job to do. The neighborhood committee of (Muslim) League would dole us and other refugees atta free. This ration too stopped after two weeks and the family faced its first starvation. I had not started writing yet. I wrote an article for newspaper Ehsan. It got published but brought not a farthing in return. In the meantime my younger brother got an order of preparing a business sign from a bakery shop in Delhi Gate with twenty rupees as a down payment. It brought flour home and everybody thanked God…. One evening I was sitting on the front plank of a closed shop along with my friend from Amrirsar, Iqbal Kausar. We heard an announcement over the radio from a hotel across the street. ‘This is Pakistan Broadcasting Service.’ Earlier, we had always heard All India Radio Lahore. ‘This is Pakistan Broadcasting Service.’ It felt good. We were convinced we are sitting in our own country.” A. Hameed was a member of a large number of intellectuals who migrated from Amritsar to Lahore. They included Saif-ud-Din Saif, Arif Abdul Mateen, Zabt Qureshi, Zaheer Kashmiri, Ahmed Rahi, Hassan Tariq and Muazaffar Ali Syed. We jokingly called the breed Amritsari school of thought. One of them, Ahmed Mushtaq, lives in Houston, Texas. He too called Hameed frequently. I talked to Hameed a day before he was admitted to the hospital on March 5. He would never admit he was seriously ill. His wife did. In one of these conversations he told me that he intends to write an autobiography and a biography of Manto in a crisp voice which negated his age. He believed in defying death. O Bullia Asan Marna Nahin, Gor Pia Koi Hor. (‘O Bulla, one is not to die, lies in the grave some other soul.’) Akmal Aleemi lives in USA |

|