Abstract

The principle of Panch Pardhan—rooted in the Gurmat concept of collective wisdom and spiritual sovereignty—has played a central role in Sikh history and theology. Epitomized by the formation of the Panj Pyare by Guru Gobind Singh Sahib in 1699, this model of decentralized yet divinely guided authority has not only sustained the Khalsa Panth during its trials but has also served as a moral compass for religious, social, and political decision-making. This paper explores the evolution of the Panch Pardhani system, from its spiritual conception by Guru Nanak Sahib to its political implications in institutions such as the Dal Khalsa, Sarbat Khalsa, and the Singh Sabha Movement. In light of this tradition, the modern governance of Sikh bodies such as the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee and the Shiromani Akali Dal are critically evaluated. The essay argues for the re-invigoration of the Panj Pardhani principle as a corrective to personality cults and centralization within Sikh political structures.

Introduction

The concept of Panch Parvan Panch Pardhan—“the five are approved, the five are supreme”—is not merely a theological construct but a revolutionary framework for egalitarian and collective decision-making in Sikhism. From Guru Nanak Sahib’s articulation of cosmic order through the five Khands (GGS, p. 8), to Guru Gobind Singh Sahib’s historic embodiment of this principle in the form of the Panj Pyare, the number five has carried sacred authority. The essence of this ideal lies in dissolving authoritarian power structures and replacing them with collective wisdom and accountability—values which remain relevant in today’s fragmented religious and political landscape.

The Spiritual Genesis of ‘Five’: From Creation to Khalsa

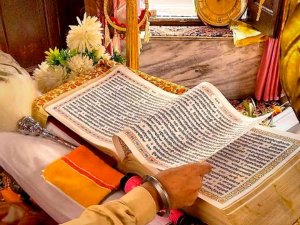

The notion of five-fold creation is articulated in the Guru Granth Sahib:

“ਪੰਚ ਪਰਵਾਣ ਪੰਚ ਪਰਧਾਨੁ ॥ ਪੰਚੇ ਪਾਵਹਿ ਦਰਗਹਿ ਮਾਨੁ ॥”

(Panch parvaan panch pardhaan…)

– Guru Granth Sahib, p. 3

Guru Nanak Sahib envisioned a cosmic framework through five progressive realms—Dharam Khand, Gyan Khand, Saram Khand, Karam Khand, and Sach Khand—that govern the soul’s journey to divine union. These stages represent ethical, intellectual, spiritual, and ultimately, mystical evolution.

This metaphysical quintet later found physical embodiment in Guru Gobind Singh Sahib’s selection of the Panj Pyare—five volunteers who symbolized absolute submission to the divine will. The Guru himself bowed before them, institutionalizing the inversion of hierarchy and proclaiming that divine guidance flows through collective conscience.

The Panj Pyare: Living Manifestation of Guru’s Will

In Vaisakhi 1699, Guru Gobind Singh Sahib inaugurated the Khalsa by selecting Bhai Daya Singh, Bhai Dharam Singh, Bhai Himmat Singh, Bhai Mohkam Singh, and Bhai Sahib Singh as the Panj Pyare. As per historical accounts (Bhai Santokh Singh, Sri Gur Pratap Suraj Granth, Ansu 23), they became the nucleus of Sikh leadership, spiritual guidance, and decision-making.

These Panj Pyare not only administered Khande di Pahul (Amrit) but also led in battle, advised the Guru, and represented the voice of the Sangat. They became living embodiments of a decentralised, consultative spiritual polity.

Even prior to 1699, the institution of five Sikhs held reverence in Sikh tradition. Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha in Mahan Kosh (1990, p. 79) notes the tradition of Guru Arjan Sahib’s five trusted Sikhs including Bhai Bidhi Chand. Similarly, Bhai Rattan Singh Bhangu in Pracheen Panth Prakash highlights:

“ਜਿਥੈ ਪੰਜ ਭੁਜੰਗੀ ਹੋਇ ॥ ਊਥੈ ਜਾਣੋ ਗੁਰਦੁਆਰਾ ਸੋਇ ॥”

(Wherever five Singhs gather, consider that place a Gurdwara.)

This signifies that the presence of five Gurmukhs constituted divine legitimacy—social, political, and spiritual.

Historical Continuity of the Panj Pardhani Framework

The Panj Pardhani principle permeated Sikh institutions across centuries:

- Dal Khalsa and Sarbat Khalsa assemblies governed by resolutions passed through the counsel of Panj Pyare.

- Military Panchayats during the Sikh Confederacy nominated five advisors per company—ensuring disciplined autonomy within a decentralized command.

- Singh Sabha Movement (1873–1920s) witnessed five primary leaders—S. Thakur Singh Sandhawalia, Prof. Gurmukh Singh, Giani Ditt Singh, S. Maya Singh, and S. Jawahar Singh—who revitalized Sikh identity through collective leadership.

Indeed, when French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed the Social Contract in 1762, and Karl Marx launched the Communist Manifesto in 1848, Guru Gobind Singh had already implemented a democratic, divine, and egalitarian order a century earlier.

The Shiromani Akali Dal and SGPC: Crisis of Centralization

Founded in 1920, the Shiromani Akali Dal emerged as a political expression of Sikh will to reclaim control over Gurdwaras. It was closely allied with the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC)—the administrative body often dubbed the ‘Parliament of the Sikhs.’

However, despite Sikh theology’s emphasis on collective leadership, the current structure of Shiromani Akali Dal has largely been presidential and personality-driven. The dominance of a single president or familial leadership runs counter to the foundational Gurmat principle of Panch Pardhani.

In matters of critical religious and sociopolitical concern, such as determining Sikh conduct, pronouncing Tankhah (penalty), or issuing Hukamnama, the mandate should not reside with a lone individual but with a Panj Pyare-like council.

A reformed Akali Dal should embrace this model—selecting five learned, virtuous, and publicly accountable Sikhs through consensus. This Panj Pardhani core should direct the policy, strategy, and arbitration processes of the party, restoring it to its theological and historical roots.

Conclusion: Reviving the Divine Republic

The Panj Pyare are not merely ceremonial figures—they are a living template of divine democracy, instituted to guard the sanctity of Sikh principles and to guide collective action. As Bhai Prahlad Singh notes:

“The Guru Khalsa is considered to be the body of the manifested Guru.”

(Rahitnama, Bhai Prahlad Singh)

The need of the hour is to re-institutionalize the Panch Pardhani ideal, not only in religious spheres like the Takhts and SGPC but also in sociopolitical bodies like the Akali Dal. By shifting from personality-led to panthic-led decision-making, the Sikh nation can reinvigorate its legacy of divine equality, fraternity, and justice.

“The true Khand resides in the Nirankar.”

– Guru Granth Sahib, p. 8

In this age of fragmentation, the sacred collective—Panj Pyare—remains the light-house of unity and accountability.

References:

- Guru Granth Sahib, various pages cited (3, 8, 736, 1041)

- Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha, Mahan Kosh, 1990, p. 79

- Bhai Santokh Singh, Sri Gur Pratap Suraj Granth, Ansu 23

- Bhai Rattan Singh Bhangu, Pracheen Panth Prakash

- Bhai Prahlad Singh, Rahitnama

- Bhai Chopa Singh, Rahitnama

- Saroop Das Bhalla, Mahima Prakash, 1773

- Proceedings of Sarbat Khalsa and Military Panchayats, historical documents

- Secondary literature on Singh Sabha Movement