|

jal thal mai joti birajat mat ki jal thal mai joti birajat mat ki

yahi katha sun ke cit cai

(Koer Singh, Gurbilas Patshahi Dasvin, 9:26)

Mother’s light permeates land and water

— the mind is delighted by hearing this story.

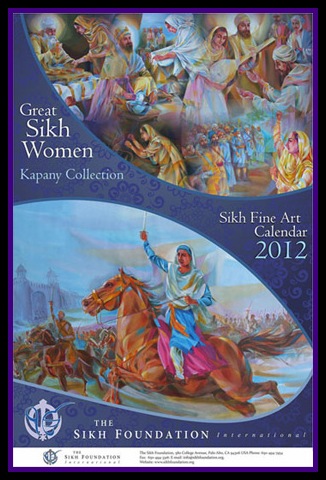

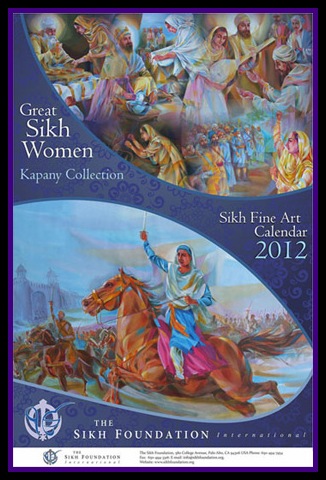

Congratulations to the Sikh Foundation for the beautiful 2012 calendar! Its paintings by the contemporary artist Sardar Devender Singh depict events deeply etched in the Sikh consciousness. What is particularly significant is the presence of women. Women protagonists have been neglected across cultures and continents. Therefore by remembering the earliest Sikh women in the language of colors, the calendar fills an important gap. From Bibi Nanaki to Maharani Jindan we witness three-dimensional figures contributing vitally to the dynamic Sikh tradition. As our eyes see them, our heads rise and our chests broaden; our sense of self-hood expands with confidence and authenticity.

Over and again philosophers from East and West have praised vision as the most important physiological faculty for the construction of individual and collective identities. The memorable images of twelve great Sikh women engaged in a wide range of activities have a visceral effect that inspires spirituality, courage, and wisdom. They belong to our past but they hold enormous possibilities for the present, and for the future of Sikhism. Seeing them at the daily level helps us respond and react meaningfully to our contemporary needs. The style of Devender Singh’s paintings is a unique fusion of traditional popular art with modern cubism. Pastel colors dominate the artist’s palette. But the yellows and blues offset by the dark brown and gray hues, render a dramatic quality to the historic scenes. The 2012 Sikh Foundation calendar triumphs splendidly in making the past vividly alive. Thanks to Uncle Kapany for his superb choice of the theme, and for his phenomenal dedication to bring the Gurus’ message into homes, offices, and campuses.

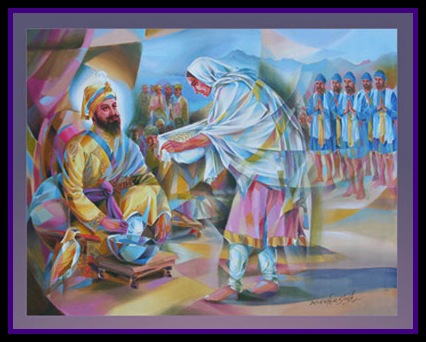

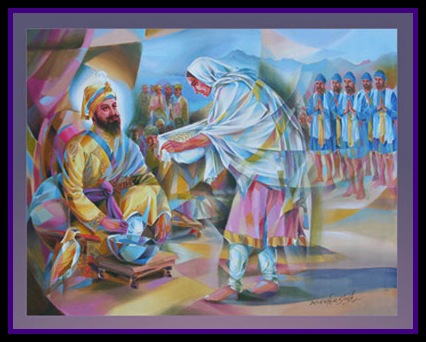

Along with the Gurus, the women are foundational to Sikh institutions, so the calendar offers a balanced view of our history. The month of August celebrates Guru Gobind Singh’s wife as an active co-partner in the momentous Khalsa institution. The artist shows Mata Sahib Kaur (Sikh memory also recalls Mata Jitoji in this event) standing in the painting, offering patase to the Guru, who is seated with a bowl in front of him. Powerful diagonals artistically flow out to connect Mataji with the Guru — her eyes with his, her white scarf with his white sash, the patase in her hand with the bowl near him. A perfect picture of togetherness, they are preparing the nourishing im+mortal fluid, the amrit (a = not + mrt = death). As the alchemy of iron mingles with the sweetness of patase, Baisakhi 1699 enters another level. The Guru’s wife is an active agent in the phenomenon of the birth of the Khalsa, and Sikhs continue to regard themselves as “the progeny of both father and mother.” A woman participates vitally in Sikhism’s most profound rite of passage. No stigma is attached to her body, and no cultural taboos are associated with her performance. In contrast with many religious traditions in which women are barred, she is essential to the sacred moment in Sikhism. It is with her input that the historic drink reaches its perfection. The inner fruition is tasted, blending physical sugar with the metaphysical experience of joy and unity. Along with the Gurus, the women are foundational to Sikh institutions, so the calendar offers a balanced view of our history. The month of August celebrates Guru Gobind Singh’s wife as an active co-partner in the momentous Khalsa institution. The artist shows Mata Sahib Kaur (Sikh memory also recalls Mata Jitoji in this event) standing in the painting, offering patase to the Guru, who is seated with a bowl in front of him. Powerful diagonals artistically flow out to connect Mataji with the Guru — her eyes with his, her white scarf with his white sash, the patase in her hand with the bowl near him. A perfect picture of togetherness, they are preparing the nourishing im+mortal fluid, the amrit (a = not + mrt = death). As the alchemy of iron mingles with the sweetness of patase, Baisakhi 1699 enters another level. The Guru’s wife is an active agent in the phenomenon of the birth of the Khalsa, and Sikhs continue to regard themselves as “the progeny of both father and mother.” A woman participates vitally in Sikhism’s most profound rite of passage. No stigma is attached to her body, and no cultural taboos are associated with her performance. In contrast with many religious traditions in which women are barred, she is essential to the sacred moment in Sikhism. It is with her input that the historic drink reaches its perfection. The inner fruition is tasted, blending physical sugar with the metaphysical experience of joy and unity.

Actually what Devender Singh expresses in colors is found in an eighteenth century textual account of the Khalsa event by Koer Singh:

jal thal mai joti birajat mat ki

yahi katha sun ke cit cai

(Koer Singh, Gurbilas Patshahi Dasvin, 9:26)

Mother’s light permeates land and water

—the mind is delighted by hearing this story.

In their own and different ways the poet and the painter evoke the “light” (joti) pervading the land and waters. Guru Gobind Singh’s wife is connected with the cosmic Mother, the matrix out of which everything that is originates and evolves. She is the life-giving “jal” (water) — all the rivers and oceans that flow through and support the earth; she is the life-giving “thal” (soil or land) — all the countries and continents that hold and sustain diverse creatures and cultures. She is crucial in the birth of the Khalsa, and as the author claims, “the mind is delighted by hearing this story.” The author and the artist urge us to remember the women and all that they did in our history. Her mnemonic presence is deemed essential as an intrinsic part of Sikh identity, and as an innately joyous phenomenon. Clearly, female reality must not be erased from consciousness; otherwise we only deprive ourselves of our authenticity and the joy that her remembrance brings.

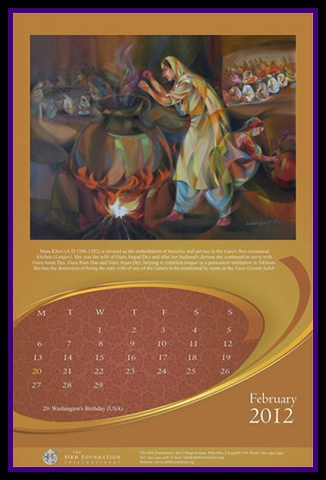

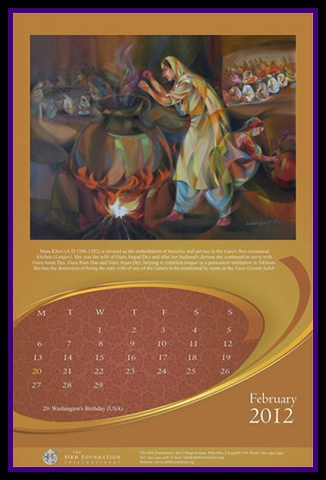

The month of February opens with Mata Khivi in a yellow outfit vigorously stirring a steaming pot over flaming wood-fire. The blazing wood matches her yellow dupatta, reflecting her spiritual radiance. Her backdrop is composed of a group of men and women preparing parshadas on the left of the canvas, and another partaking langar on the right. At the centre is Mata Khivi, fondly remembered for her liberal direction of langar. As we see her completely absorbed in feeding the community, the verse from the Guru Granth Sahib acquires a tangible reality: The month of February opens with Mata Khivi in a yellow outfit vigorously stirring a steaming pot over flaming wood-fire. The blazing wood matches her yellow dupatta, reflecting her spiritual radiance. Her backdrop is composed of a group of men and women preparing parshadas on the left of the canvas, and another partaking langar on the right. At the centre is Mata Khivi, fondly remembered for her liberal direction of langar. As we see her completely absorbed in feeding the community, the verse from the Guru Granth Sahib acquires a tangible reality:

balvand khivi nek jan jis bahuti chhao patrali

langar daulat vandiai ras amrit kh_eer ghiali

(GGS: 967).

Says Balwand, noble Khivi supplies Immense leafy shade to people,

She richly distributes langar, Her kheer drenched in ghee is ambrosial!

With Mata Khivi’s generous supervision and her plentiful supply of mouth-watering kheer (rice pudding), the tradition of langar became a real feast rather than just a symbolic meal. Furthermore, the image of her stirring the cauldron concretizes an important ideal of Sikh life—the victory of degh (cooking pot, so that nobody goes hungry). Mata Khivi’s visual configuration endows the recitation of the liturgical Ardas (degh tegh fateh – victory to the cooking pot and the sword) with a new impulse that can engender a more wholesome mode of existence.

The next painting is that of Mata Gujri in a white outfit, sitting with her young grandsons. While she appears to be speaking, the two boys are avidly listening to her. The variegated nocturnal blue landscape gives a chilly feeling, evoking the historical cold fort where she was held captive with her two grandsons. But rather than a weak imprisoned figure we encounter in the painting a real force — exuding confidence, intellectual vigor, and a warm spiritual halo. Her hands in motion bespeak of her stirring the imagination and spirit of her audience. The boys subsequently withstood their cruel death because of Mata Gujri’s courageous personality and her heroic narratives. Clearly across generations Sikh mothers and grandmothers have been crucial in the perpetuation of supreme heroism and moral fervor. The next painting is that of Mata Gujri in a white outfit, sitting with her young grandsons. While she appears to be speaking, the two boys are avidly listening to her. The variegated nocturnal blue landscape gives a chilly feeling, evoking the historical cold fort where she was held captive with her two grandsons. But rather than a weak imprisoned figure we encounter in the painting a real force — exuding confidence, intellectual vigor, and a warm spiritual halo. Her hands in motion bespeak of her stirring the imagination and spirit of her audience. The boys subsequently withstood their cruel death because of Mata Gujri’s courageous personality and her heroic narratives. Clearly across generations Sikh mothers and grandmothers have been crucial in the perpetuation of supreme heroism and moral fervor.

The calendar also displays female paradigms fighting battles to change the course of history. Included are Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur. When Mai Bhago saw how some Sikhs of her area had fled Anandpur in the face of the privations brought on by a prolonged siege, she chided them with pusillanimity. She led them back to fight for Guru Gobind Singh. The painting records her fighting valiantly in the battle that ensued at Khidrana in 1705. Almost a century later, Sada Kaur proved to be instrumental to her nineteen-year old son-in-law, the future Maharaja Ranjit Singh. A passionate patriot with unparalleled administrative skills, Sada Kaur was the architect who really united the Punjab into a Sikh State for the young Ranjit Singh. She possessed great courage on the battlefield as well, but the best part of her triumph lay in victory without bloodshed. The painting depicts her capture of the fort of Lahore in 1799, which led to the establishment of the Sikh Empire. The calendar also displays female paradigms fighting battles to change the course of history. Included are Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur. When Mai Bhago saw how some Sikhs of her area had fled Anandpur in the face of the privations brought on by a prolonged siege, she chided them with pusillanimity. She led them back to fight for Guru Gobind Singh. The painting records her fighting valiantly in the battle that ensued at Khidrana in 1705. Almost a century later, Sada Kaur proved to be instrumental to her nineteen-year old son-in-law, the future Maharaja Ranjit Singh. A passionate patriot with unparalleled administrative skills, Sada Kaur was the architect who really united the Punjab into a Sikh State for the young Ranjit Singh. She possessed great courage on the battlefield as well, but the best part of her triumph lay in victory without bloodshed. The painting depicts her capture of the fort of Lahore in 1799, which led to the establishment of the Sikh Empire.

But rather than the Guru or the Maharaja alongside whom they fought, Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur occupy centre space in the calendar paintings. Dressed in chooridars, flowing shirts, and dupattas covering their heads, each is seen riding horses that gallop faster than wind. Both wield long shining swords with enormous ease that is most threatening for the enemy. Angry male opponents—both cavalry and infantry—surround Mai Bhago, portrayed in a three quarter profile. We see her close-up as she combats them all fearlessly. Sada Kaur is portrayed from a wider angle, which shows her leading her warrior comrades. Most of them are rendered in an impressionistic style except for one on her right, who we assume is the future Sikh Maharaja. The figure of Sada Kaur is juxtaposed vertically to the blue skies and horizontally to the Lahore fort. The scene foreshadows her victory. These palpable images of Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur fighting valiantly send internal messages to their spectators; they reproduce reflexes that we fight against injustice confronting us today. They fill us with optimism that we can change oppressive customs and discriminatory attitudes, and live the egalitarian and liberating life intended by our Gurus. But rather than the Guru or the Maharaja alongside whom they fought, Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur occupy centre space in the calendar paintings. Dressed in chooridars, flowing shirts, and dupattas covering their heads, each is seen riding horses that gallop faster than wind. Both wield long shining swords with enormous ease that is most threatening for the enemy. Angry male opponents—both cavalry and infantry—surround Mai Bhago, portrayed in a three quarter profile. We see her close-up as she combats them all fearlessly. Sada Kaur is portrayed from a wider angle, which shows her leading her warrior comrades. Most of them are rendered in an impressionistic style except for one on her right, who we assume is the future Sikh Maharaja. The figure of Sada Kaur is juxtaposed vertically to the blue skies and horizontally to the Lahore fort. The scene foreshadows her victory. These palpable images of Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur fighting valiantly send internal messages to their spectators; they reproduce reflexes that we fight against injustice confronting us today. They fill us with optimism that we can change oppressive customs and discriminatory attitudes, and live the egalitarian and liberating life intended by our Gurus.

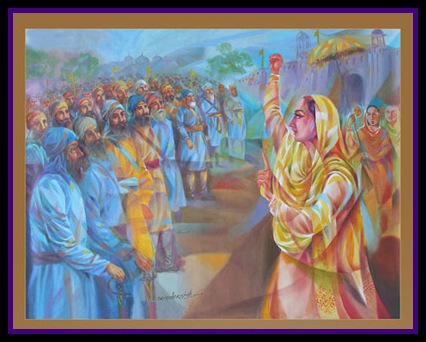

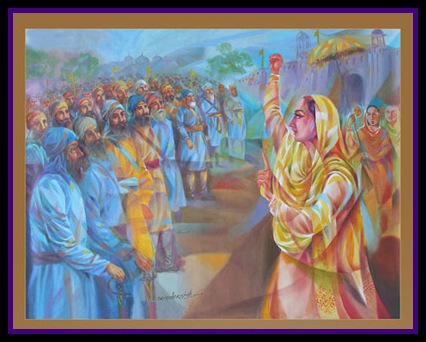

The final painting is that of Maharani Jindan. Regent to her five-year old son Dalip, crowned as the Maharaja of the Sikh Kingdom in 1843, Jindan here is depicted as the symbol of Sikh sovereignty. She is not observing the custom of purdah prevalent in her society. To the contrary, she is squarely facing her male Khalsa army. Behind her is an entourage of women, with one holding a royal umbrella in attendance. With her right hand stretched up in a fist, and the index finger of her left pointing sternly, she is the embodiment of a robust commander galvanizing her troops. The painting explains why the British Raj was in awe of her, calling her the only courageous “man” in the area. With her sharp intelligence and acute statesmanship, Jindan was able to restore a balance between the Khalsa army and the civil administration. After the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, the British administrators were so threatened by her leadership qualities that they expelled her from the province, and interned her at Benares under strict surveillance. Even after her dramatic escape to Nepal, they kept a vigilant eye on her, and when her son carried her final remains from England to disperse them in the Punjab, he was refused. Her last years had been spent in Kensington as a frail woman of poor eyesight without much jewelry or attendants. In Devender Singh’s visual commemoration, the feisty Jindan continues to electrify not only her mid-nineteenth century subjects but also her modern spectators. The final painting is that of Maharani Jindan. Regent to her five-year old son Dalip, crowned as the Maharaja of the Sikh Kingdom in 1843, Jindan here is depicted as the symbol of Sikh sovereignty. She is not observing the custom of purdah prevalent in her society. To the contrary, she is squarely facing her male Khalsa army. Behind her is an entourage of women, with one holding a royal umbrella in attendance. With her right hand stretched up in a fist, and the index finger of her left pointing sternly, she is the embodiment of a robust commander galvanizing her troops. The painting explains why the British Raj was in awe of her, calling her the only courageous “man” in the area. With her sharp intelligence and acute statesmanship, Jindan was able to restore a balance between the Khalsa army and the civil administration. After the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, the British administrators were so threatened by her leadership qualities that they expelled her from the province, and interned her at Benares under strict surveillance. Even after her dramatic escape to Nepal, they kept a vigilant eye on her, and when her son carried her final remains from England to disperse them in the Punjab, he was refused. Her last years had been spent in Kensington as a frail woman of poor eyesight without much jewelry or attendants. In Devender Singh’s visual commemoration, the feisty Jindan continues to electrify not only her mid-nineteenth century subjects but also her modern spectators.

This rich collection of paintings instinctually shows that spiritual quest and action are not disparate or antithetical; rather, they are complementary states. For Sikhs today, these twelve historic females prove to be a self-affirming phenomenon. They serve as role models to build self esteem and encourage fulfillment of individual potential. Simultaneously they provide insights into Sikh theology and ontology. The flesh and blood mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters were influential in shaping the worldview of the Gurus. The set of paintings opens with Bibi Nanaki handing the rabab to Bhai Mardana. When we see Bibi Nanaki in the forefront we realize her influence on her younger brother’s social and religious consciousness, — which was then carried on by his nine successor Gurus. The founder Sikh Guru spent a lot of his formative years with sister Nanaki, and even went to live with her in her new home after she was married. The Guru’s condemnation of the beliefs in purdah (segregation and veiling), sati (upper-class women obligated to die in the funeral pyre of their husbands), and pollution (associated with menstruation and childbirth) would have been affected by his close relationship with his sister. Parallel to Mary Magdalene in the Christian context, Bibi Nanaki was the one to recognize Guru Nanak’s revelation. We can interpret her gesture of handing the rabab as an invitation to Bhai Mardana that he accompany the hymns of divine epiphany with his music. This exquisite painting in pastel yellows discloses not only the bond between the sister and brother, but also between Sikh and Muslim, visual and aural, word and music, divine revelation and aesthetic experience. The scriptural verse “avhu bh_ain_e gal milah – come o’sisters let us embrace” (GGS: 17) is enriched by Devender Singh’s visual hermeneutics, it ushers us into wide emotional and spiritual horizons. This rich collection of paintings instinctually shows that spiritual quest and action are not disparate or antithetical; rather, they are complementary states. For Sikhs today, these twelve historic females prove to be a self-affirming phenomenon. They serve as role models to build self esteem and encourage fulfillment of individual potential. Simultaneously they provide insights into Sikh theology and ontology. The flesh and blood mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters were influential in shaping the worldview of the Gurus. The set of paintings opens with Bibi Nanaki handing the rabab to Bhai Mardana. When we see Bibi Nanaki in the forefront we realize her influence on her younger brother’s social and religious consciousness, — which was then carried on by his nine successor Gurus. The founder Sikh Guru spent a lot of his formative years with sister Nanaki, and even went to live with her in her new home after she was married. The Guru’s condemnation of the beliefs in purdah (segregation and veiling), sati (upper-class women obligated to die in the funeral pyre of their husbands), and pollution (associated with menstruation and childbirth) would have been affected by his close relationship with his sister. Parallel to Mary Magdalene in the Christian context, Bibi Nanaki was the one to recognize Guru Nanak’s revelation. We can interpret her gesture of handing the rabab as an invitation to Bhai Mardana that he accompany the hymns of divine epiphany with his music. This exquisite painting in pastel yellows discloses not only the bond between the sister and brother, but also between Sikh and Muslim, visual and aural, word and music, divine revelation and aesthetic experience. The scriptural verse “avhu bh_ain_e gal milah – come o’sisters let us embrace” (GGS: 17) is enriched by Devender Singh’s visual hermeneutics, it ushers us into wide emotional and spiritual horizons.

One of the most endearing scenes in the calendar is that of Bibi Bhani standing between her elderly father (Guru Amar Das) having his meal seated on a cot, and her baby son (Guru Arjan) playing beside her. This very ordinary scene underscores an extraordinary principle of Sikh metaphysics: the coalescence of the sacred and the secular. The transcendent Divine in Sikhism is not disconnected from the world, but is an intrinsic part of daily life. A major factor in the Gurus’ vehement rejection of asceticism and renunciation would be the constructive relationships they had with their own families as captured in this father-daughter, mother-son scene. The brush strokes of tender love sweeping these three protagonists resonate throughout Sikh scripture. No wonder the Guru Granth Sahib claims, “Amidst mother, father, brother, son, and wife, has the Divine yoked us” (GGS: 77). In these divinely bound relationships, every human relationship is vitally significant. One of the most endearing scenes in the calendar is that of Bibi Bhani standing between her elderly father (Guru Amar Das) having his meal seated on a cot, and her baby son (Guru Arjan) playing beside her. This very ordinary scene underscores an extraordinary principle of Sikh metaphysics: the coalescence of the sacred and the secular. The transcendent Divine in Sikhism is not disconnected from the world, but is an intrinsic part of daily life. A major factor in the Gurus’ vehement rejection of asceticism and renunciation would be the constructive relationships they had with their own families as captured in this father-daughter, mother-son scene. The brush strokes of tender love sweeping these three protagonists resonate throughout Sikh scripture. No wonder the Guru Granth Sahib claims, “Amidst mother, father, brother, son, and wife, has the Divine yoked us” (GGS: 77). In these divinely bound relationships, every human relationship is vitally significant.

The 2012 calendar paintings illustrate the respect and love the Gurus had for their biological relatives and those with whom they associated. Their existential reality correlates with their theological vision wherein female and male dimensions run parallel: “ape purakh ape hi nar – itself male, itself is female” (GGS: 1020). The baby son of Bibi Bhani would subsequently voice an inclusive Sikh theological experience: “tun mera pita tun hai mera mata — You are my father, you are my mother…”(GGS: 103). The Gurus passionately embrace the Divine in numerous relationships. Their sense of plenitude strips off patriarchal stratifications and blots out masculine identity as the norm for imaging that One. Indeed their theological imaginary shatters centuries-old images of male dominance and opens up a space to experience the Infinite in important new ways. The existence of the singular transcendent One beyond all categories is the basic Sikh creed. Yet the Gurus were able to relate to this One in many passionate ways, and offer a balanced perspective so crucial for mental and spiritual health. The 2012 calendar brings to fore women like Bibi Nanaki, Mata Khivi, Bibi Amaro, Bibi Bhani, Mata Ganga, and Mata Gujri who impacted the Gurus’ worldview, and in turn will continue to impact generations of Sikh men and women. The commitment and spirituality of the women displayed in these calendar images on our walls will guide us to recognize those qualities in all the women we are in touch with in our own lives, and our lips will utter the Granthian exaltation “dhan janedi maia — blessed are the mothers (GGS: 513).

Because of their positive personal experience, the Gurus did not hold ontological perspectives that view life negatively. Having a mother like Bibi Bhani and a wife like Mata Ganga (who we see in another painting in the calendar serenely seated on a platform against a royal cushion) would have inspired Guru Arjan to affirm: “spiritual liberation is attained in the midst of laughing, playing, dressing up, and eating — hasandia khelandia painandia khavandia viche hovai mukt” (GGS: 522). The horizon of the physical, which has been severed by the patriarchal metaphysical order in which death functions as the fundamental paradigm, is protected by women’s biological functions. According to feminist scholars, the obsession with death is connected to an “obsession with female bodies, and the denial of death and efforts to master it are connected with a deep-seated misogyny.” So the various forms of dominance — racism, capitalism, colonialism, homophobia, ecological destruction — are manifestations of the need to conquer death (Grace Jantzen, Becoming Divine: Towards a Feminist Philosophy of Religion, 1999: 132). Sikhism overturns such perspectives and celebrates the Divine in every morsel of food and every sip — we see Guru Amar Das partaking in the presence of his daughter during the month of April.

And the grandson too is trying to stand up and witness the magic of life! This canvas with the white bearded Nanak 3 and the crawling toddler (the future Nanak 5) poignantly captures the intersection of past and future; it is a celebration of the flux of time. For the Gurus temporality is an essential characteristic of the infinite Being. We hear them repeatedly marvel at the lunar and solar systems, the movements making up days and dates, the cyclic rhythm of seasons during the twelve months…. In the opening line of his Japji Guru Nanak states, “ad sacu jugadi sacu hai bhi sacu nanak hosi bhi sacu — Truth was in the beginning, Truth has been through the cycles, Truth is, and Truth says Nanak, will be ever more.” By starting our new year — and each new month — with this lovely calendar from the Sikh Foundation, we will remind ourselves of the significance of each moment. Memory is not merely a psychological faculty but an essential component of the historical being (Gadamer, Truth and Method, 1989: 17). This set of kaleidoscopic paintings of historic Sikh women charges us to live in family, friends, and community with such beauty and spirituality that we share every second, minute, hour, day, week, and month with our singular Divine.

visue chasia gh_aria pahra thiti vari mahu hoa

suraj eko rut anek nanak karte ke kete ves

(GGS: 12)

Seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks Turn into months—

The sun is one though seasons are many, O’ Nanak, the Creator has so many forms!

####

Devender Singh, b.1947, is an internationally renowned artist and the recipient of numerous awards and honors. A master of both realistic and abstract, his art brings alive the glorious moments of Sikh history and Punjabi culture. Amongst his best works are the Bara Maha Series of oil paintings which are based on the compositions of Guru Nanak and Guru Arjan Dev. He is respected for his much loved illustrations for the sikh comics of Amar Chitra Katha and countless books. His works adorn acclaimed museums and hold a place of pride in private collections worldwide.

Nikky Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College, and the Chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Her interests focus on poetics and feminist issues. Nikky Singh has published extensively in the field of Sikhism, including The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (HarperCollins and Penguin), Metaphysics and Physics of the Guru Granth Sahib (Sterling). She has published over 45 Journal Articles and Chapters in books, and has given over hundred lectures in North America, England, France, India, and Singapore. Her views have also been aired on television and radio in America, Canada, and India. Over the years her scholarship has been recognized with numerous awards and honors. Nikky Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College, and the Chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Her interests focus on poetics and feminist issues. Nikky Singh has published extensively in the field of Sikhism, including The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (HarperCollins and Penguin), Metaphysics and Physics of the Guru Granth Sahib (Sterling). She has published over 45 Journal Articles and Chapters in books, and has given over hundred lectures in North America, England, France, India, and Singapore. Her views have also been aired on television and radio in America, Canada, and India. Over the years her scholarship has been recognized with numerous awards and honors.

Pre-Order your copy Now! Click here |

jal thal mai joti birajat mat ki

jal thal mai joti birajat mat ki Along with the Gurus, the women are foundational to Sikh institutions, so the calendar offers a balanced view of our history. The month of August celebrates Guru Gobind Singh’s wife as an active co-partner in the momentous Khalsa institution. The artist shows Mata Sahib Kaur (Sikh memory also recalls Mata Jitoji in this event) standing in the painting, offering patase to the Guru, who is seated with a bowl in front of him. Powerful diagonals artistically flow out to connect Mataji with the Guru — her eyes with his, her white scarf with his white sash, the patase in her hand with the bowl near him. A perfect picture of togetherness, they are preparing the nourishing im+mortal fluid, the amrit (a = not + mrt = death). As the alchemy of iron mingles with the sweetness of patase, Baisakhi 1699 enters another level. The Guru’s wife is an active agent in the phenomenon of the birth of the Khalsa, and Sikhs continue to regard themselves as “the progeny of both father and mother.” A woman participates vitally in Sikhism’s most profound rite of passage. No stigma is attached to her body, and no cultural taboos are associated with her performance. In contrast with many religious traditions in which women are barred, she is essential to the sacred moment in Sikhism. It is with her input that the historic drink reaches its perfection. The inner fruition is tasted, blending physical sugar with the metaphysical experience of joy and unity.

Along with the Gurus, the women are foundational to Sikh institutions, so the calendar offers a balanced view of our history. The month of August celebrates Guru Gobind Singh’s wife as an active co-partner in the momentous Khalsa institution. The artist shows Mata Sahib Kaur (Sikh memory also recalls Mata Jitoji in this event) standing in the painting, offering patase to the Guru, who is seated with a bowl in front of him. Powerful diagonals artistically flow out to connect Mataji with the Guru — her eyes with his, her white scarf with his white sash, the patase in her hand with the bowl near him. A perfect picture of togetherness, they are preparing the nourishing im+mortal fluid, the amrit (a = not + mrt = death). As the alchemy of iron mingles with the sweetness of patase, Baisakhi 1699 enters another level. The Guru’s wife is an active agent in the phenomenon of the birth of the Khalsa, and Sikhs continue to regard themselves as “the progeny of both father and mother.” A woman participates vitally in Sikhism’s most profound rite of passage. No stigma is attached to her body, and no cultural taboos are associated with her performance. In contrast with many religious traditions in which women are barred, she is essential to the sacred moment in Sikhism. It is with her input that the historic drink reaches its perfection. The inner fruition is tasted, blending physical sugar with the metaphysical experience of joy and unity. The month of February opens with Mata Khivi in a yellow outfit vigorously stirring a steaming pot over flaming wood-fire. The blazing wood matches her yellow dupatta, reflecting her spiritual radiance. Her backdrop is composed of a group of men and women preparing parshadas on the left of the canvas, and another partaking langar on the right. At the centre is Mata Khivi, fondly remembered for her liberal direction of langar. As we see her completely absorbed in feeding the community, the verse from the Guru Granth Sahib acquires a tangible reality:

The month of February opens with Mata Khivi in a yellow outfit vigorously stirring a steaming pot over flaming wood-fire. The blazing wood matches her yellow dupatta, reflecting her spiritual radiance. Her backdrop is composed of a group of men and women preparing parshadas on the left of the canvas, and another partaking langar on the right. At the centre is Mata Khivi, fondly remembered for her liberal direction of langar. As we see her completely absorbed in feeding the community, the verse from the Guru Granth Sahib acquires a tangible reality: The next painting is that of Mata Gujri in a white outfit, sitting with her young grandsons. While she appears to be speaking, the two boys are avidly listening to her. The variegated nocturnal blue landscape gives a chilly feeling, evoking the historical cold fort where she was held captive with her two grandsons. But rather than a weak imprisoned figure we encounter in the painting a real force — exuding confidence, intellectual vigor, and a warm spiritual halo. Her hands in motion bespeak of her stirring the imagination and spirit of her audience. The boys subsequently withstood their cruel death because of Mata Gujri’s courageous personality and her heroic narratives. Clearly across generations Sikh mothers and grandmothers have been crucial in the perpetuation of supreme heroism and moral fervor.

The next painting is that of Mata Gujri in a white outfit, sitting with her young grandsons. While she appears to be speaking, the two boys are avidly listening to her. The variegated nocturnal blue landscape gives a chilly feeling, evoking the historical cold fort where she was held captive with her two grandsons. But rather than a weak imprisoned figure we encounter in the painting a real force — exuding confidence, intellectual vigor, and a warm spiritual halo. Her hands in motion bespeak of her stirring the imagination and spirit of her audience. The boys subsequently withstood their cruel death because of Mata Gujri’s courageous personality and her heroic narratives. Clearly across generations Sikh mothers and grandmothers have been crucial in the perpetuation of supreme heroism and moral fervor. The calendar also displays female paradigms fighting battles to change the course of history. Included are Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur. When Mai Bhago saw how some Sikhs of her area had fled Anandpur in the face of the privations brought on by a prolonged siege, she chided them with pusillanimity. She led them back to fight for Guru Gobind Singh. The painting records her fighting valiantly in the battle that ensued at Khidrana in 1705. Almost a century later, Sada Kaur proved to be instrumental to her nineteen-year old son-in-law, the future Maharaja Ranjit Singh. A passionate patriot with unparalleled administrative skills, Sada Kaur was the architect who really united the Punjab into a Sikh State for the young Ranjit Singh. She possessed great courage on the battlefield as well, but the best part of her triumph lay in victory without bloodshed. The painting depicts her capture of the fort of Lahore in 1799, which led to the establishment of the Sikh Empire.

The calendar also displays female paradigms fighting battles to change the course of history. Included are Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur. When Mai Bhago saw how some Sikhs of her area had fled Anandpur in the face of the privations brought on by a prolonged siege, she chided them with pusillanimity. She led them back to fight for Guru Gobind Singh. The painting records her fighting valiantly in the battle that ensued at Khidrana in 1705. Almost a century later, Sada Kaur proved to be instrumental to her nineteen-year old son-in-law, the future Maharaja Ranjit Singh. A passionate patriot with unparalleled administrative skills, Sada Kaur was the architect who really united the Punjab into a Sikh State for the young Ranjit Singh. She possessed great courage on the battlefield as well, but the best part of her triumph lay in victory without bloodshed. The painting depicts her capture of the fort of Lahore in 1799, which led to the establishment of the Sikh Empire. But rather than the Guru or the Maharaja alongside whom they fought, Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur occupy centre space in the calendar paintings. Dressed in chooridars, flowing shirts, and dupattas covering their heads, each is seen riding horses that gallop faster than wind. Both wield long shining swords with enormous ease that is most threatening for the enemy. Angry male opponents—both cavalry and infantry—surround Mai Bhago, portrayed in a three quarter profile. We see her close-up as she combats them all fearlessly. Sada Kaur is portrayed from a wider angle, which shows her leading her warrior comrades. Most of them are rendered in an impressionistic style except for one on her right, who we assume is the future Sikh Maharaja. The figure of Sada Kaur is juxtaposed vertically to the blue skies and horizontally to the Lahore fort. The scene foreshadows her victory. These palpable images of Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur fighting valiantly send internal messages to their spectators; they reproduce reflexes that we fight against injustice confronting us today. They fill us with optimism that we can change oppressive customs and discriminatory attitudes, and live the egalitarian and liberating life intended by our Gurus.

But rather than the Guru or the Maharaja alongside whom they fought, Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur occupy centre space in the calendar paintings. Dressed in chooridars, flowing shirts, and dupattas covering their heads, each is seen riding horses that gallop faster than wind. Both wield long shining swords with enormous ease that is most threatening for the enemy. Angry male opponents—both cavalry and infantry—surround Mai Bhago, portrayed in a three quarter profile. We see her close-up as she combats them all fearlessly. Sada Kaur is portrayed from a wider angle, which shows her leading her warrior comrades. Most of them are rendered in an impressionistic style except for one on her right, who we assume is the future Sikh Maharaja. The figure of Sada Kaur is juxtaposed vertically to the blue skies and horizontally to the Lahore fort. The scene foreshadows her victory. These palpable images of Mai Bhago and Sada Kaur fighting valiantly send internal messages to their spectators; they reproduce reflexes that we fight against injustice confronting us today. They fill us with optimism that we can change oppressive customs and discriminatory attitudes, and live the egalitarian and liberating life intended by our Gurus. The final painting is that of Maharani Jindan. Regent to her five-year old son Dalip, crowned as the Maharaja of the Sikh Kingdom in 1843, Jindan here is depicted as the symbol of Sikh sovereignty. She is not observing the custom of purdah prevalent in her society. To the contrary, she is squarely facing her male Khalsa army. Behind her is an entourage of women, with one holding a royal umbrella in attendance. With her right hand stretched up in a fist, and the index finger of her left pointing sternly, she is the embodiment of a robust commander galvanizing her troops. The painting explains why the British Raj was in awe of her, calling her the only courageous “man” in the area. With her sharp intelligence and acute statesmanship, Jindan was able to restore a balance between the Khalsa army and the civil administration. After the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, the British administrators were so threatened by her leadership qualities that they expelled her from the province, and interned her at Benares under strict surveillance. Even after her dramatic escape to Nepal, they kept a vigilant eye on her, and when her son carried her final remains from England to disperse them in the Punjab, he was refused. Her last years had been spent in Kensington as a frail woman of poor eyesight without much jewelry or attendants. In Devender Singh’s visual commemoration, the feisty Jindan continues to electrify not only her mid-nineteenth century subjects but also her modern spectators.

The final painting is that of Maharani Jindan. Regent to her five-year old son Dalip, crowned as the Maharaja of the Sikh Kingdom in 1843, Jindan here is depicted as the symbol of Sikh sovereignty. She is not observing the custom of purdah prevalent in her society. To the contrary, she is squarely facing her male Khalsa army. Behind her is an entourage of women, with one holding a royal umbrella in attendance. With her right hand stretched up in a fist, and the index finger of her left pointing sternly, she is the embodiment of a robust commander galvanizing her troops. The painting explains why the British Raj was in awe of her, calling her the only courageous “man” in the area. With her sharp intelligence and acute statesmanship, Jindan was able to restore a balance between the Khalsa army and the civil administration. After the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, the British administrators were so threatened by her leadership qualities that they expelled her from the province, and interned her at Benares under strict surveillance. Even after her dramatic escape to Nepal, they kept a vigilant eye on her, and when her son carried her final remains from England to disperse them in the Punjab, he was refused. Her last years had been spent in Kensington as a frail woman of poor eyesight without much jewelry or attendants. In Devender Singh’s visual commemoration, the feisty Jindan continues to electrify not only her mid-nineteenth century subjects but also her modern spectators. This rich collection of paintings instinctually shows that spiritual quest and action are not disparate or antithetical; rather, they are complementary states. For Sikhs today, these twelve historic females prove to be a self-affirming phenomenon. They serve as role models to build self esteem and encourage fulfillment of individual potential. Simultaneously they provide insights into Sikh theology and ontology. The flesh and blood mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters were influential in shaping the worldview of the Gurus. The set of paintings opens with Bibi Nanaki handing the rabab to Bhai Mardana. When we see Bibi Nanaki in the forefront we realize her influence on her younger brother’s social and religious consciousness, — which was then carried on by his nine successor Gurus. The founder Sikh Guru spent a lot of his formative years with sister Nanaki, and even went to live with her in her new home after she was married. The Guru’s condemnation of the beliefs in purdah (segregation and veiling), sati (upper-class women obligated to die in the funeral pyre of their husbands), and pollution (associated with menstruation and childbirth) would have been affected by his close relationship with his sister. Parallel to Mary Magdalene in the Christian context, Bibi Nanaki was the one to recognize Guru Nanak’s revelation. We can interpret her gesture of handing the rabab as an invitation to Bhai Mardana that he accompany the hymns of divine epiphany with his music. This exquisite painting in pastel yellows discloses not only the bond between the sister and brother, but also between Sikh and Muslim, visual and aural, word and music, divine revelation and aesthetic experience. The scriptural verse “avhu bh_ain_e gal milah – come o’sisters let us embrace” (GGS: 17) is enriched by Devender Singh’s visual hermeneutics, it ushers us into wide emotional and spiritual horizons.

This rich collection of paintings instinctually shows that spiritual quest and action are not disparate or antithetical; rather, they are complementary states. For Sikhs today, these twelve historic females prove to be a self-affirming phenomenon. They serve as role models to build self esteem and encourage fulfillment of individual potential. Simultaneously they provide insights into Sikh theology and ontology. The flesh and blood mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters were influential in shaping the worldview of the Gurus. The set of paintings opens with Bibi Nanaki handing the rabab to Bhai Mardana. When we see Bibi Nanaki in the forefront we realize her influence on her younger brother’s social and religious consciousness, — which was then carried on by his nine successor Gurus. The founder Sikh Guru spent a lot of his formative years with sister Nanaki, and even went to live with her in her new home after she was married. The Guru’s condemnation of the beliefs in purdah (segregation and veiling), sati (upper-class women obligated to die in the funeral pyre of their husbands), and pollution (associated with menstruation and childbirth) would have been affected by his close relationship with his sister. Parallel to Mary Magdalene in the Christian context, Bibi Nanaki was the one to recognize Guru Nanak’s revelation. We can interpret her gesture of handing the rabab as an invitation to Bhai Mardana that he accompany the hymns of divine epiphany with his music. This exquisite painting in pastel yellows discloses not only the bond between the sister and brother, but also between Sikh and Muslim, visual and aural, word and music, divine revelation and aesthetic experience. The scriptural verse “avhu bh_ain_e gal milah – come o’sisters let us embrace” (GGS: 17) is enriched by Devender Singh’s visual hermeneutics, it ushers us into wide emotional and spiritual horizons. One of the most endearing scenes in the calendar is that of Bibi Bhani standing between her elderly father (Guru Amar Das) having his meal seated on a cot, and her baby son (Guru Arjan) playing beside her. This very ordinary scene underscores an extraordinary principle of Sikh metaphysics: the coalescence of the sacred and the secular. The transcendent Divine in Sikhism is not disconnected from the world, but is an intrinsic part of daily life. A major factor in the Gurus’ vehement rejection of asceticism and renunciation would be the constructive relationships they had with their own families as captured in this father-daughter, mother-son scene. The brush strokes of tender love sweeping these three protagonists resonate throughout Sikh scripture. No wonder the Guru Granth Sahib claims, “Amidst mother, father, brother, son, and wife, has the Divine yoked us” (GGS: 77). In these divinely bound relationships, every human relationship is vitally significant.

One of the most endearing scenes in the calendar is that of Bibi Bhani standing between her elderly father (Guru Amar Das) having his meal seated on a cot, and her baby son (Guru Arjan) playing beside her. This very ordinary scene underscores an extraordinary principle of Sikh metaphysics: the coalescence of the sacred and the secular. The transcendent Divine in Sikhism is not disconnected from the world, but is an intrinsic part of daily life. A major factor in the Gurus’ vehement rejection of asceticism and renunciation would be the constructive relationships they had with their own families as captured in this father-daughter, mother-son scene. The brush strokes of tender love sweeping these three protagonists resonate throughout Sikh scripture. No wonder the Guru Granth Sahib claims, “Amidst mother, father, brother, son, and wife, has the Divine yoked us” (GGS: 77). In these divinely bound relationships, every human relationship is vitally significant.

Nikky Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College, and the Chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Her interests focus on poetics and feminist issues. Nikky Singh has published extensively in the field of Sikhism, including The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (HarperCollins and Penguin), Metaphysics and Physics of the Guru Granth Sahib (Sterling). She has published over 45 Journal Articles and Chapters in books, and has given over hundred lectures in North America, England, France, India, and Singapore. Her views have also been aired on television and radio in America, Canada, and India. Over the years her scholarship has been recognized with numerous awards and honors.

Nikky Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College, and the Chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Her interests focus on poetics and feminist issues. Nikky Singh has published extensively in the field of Sikhism, including The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (HarperCollins and Penguin), Metaphysics and Physics of the Guru Granth Sahib (Sterling). She has published over 45 Journal Articles and Chapters in books, and has given over hundred lectures in North America, England, France, India, and Singapore. Her views have also been aired on television and radio in America, Canada, and India. Over the years her scholarship has been recognized with numerous awards and honors.