In Portland, Astoria, Ghadar Party plotted revolt against British

|

by: PHOTO BY KESAR SINGH, COURTESY OF THE AMARJIT CHANDAN COLLECTION - Sohan Singh Bhakna, second from the right, was arrested and jailed for his role in the Ghadar Partys abortive revolt against British rule in India. The former St. Johns mill worker, a major organizer and leader of the party, is shown here in 1938 at Amritsar Railway Station. |

Thursday, 19 September 2013: When Gurpreet Kaur was growing up in India, she learned in middle school about the brave freedom fighters who formed an overseas revolutionary movement a century ago and then returned home to seek the overthrow of British colonialism.

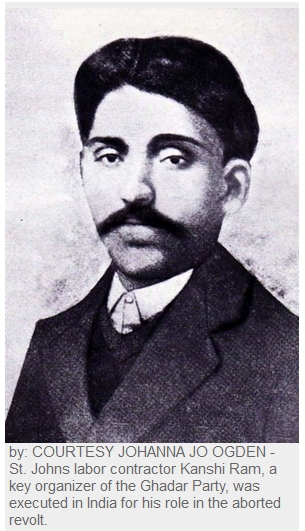

Kaur recalls dutifully memorizing the names of key martyrs like Sohan Singh Bhakna and Kanshi Ram, and the name of the boat they took back to India.

What the Beaverton resident didn’t know, until very recently, was that Bhakna and Ram hailed from Portland, and that the Ghadar Party they helped build was forged largely in Portland and Astoria. In fact, hardly anyone in the world knew until Portland historian Johanna “Jo” Ogden started digging into the matter five years ago and shared her findings last summer in the “Oregon Historical Quarterly,” a scholarly journal published by the Oregon Historical Society.

Poring through back issues of newspapers, oral histories and other materials, Ogden found that several hundred “Punjabis” settled in Oregon towns along the Columbia River in the years before World War I. Then — when the Ghadar Party deemed it a ripe time to foment armed insurrection while Britain was preoccupied by the war — the community largely vanished, mostly to take up arms against British colonizers back home.

Though the armed revolt was quashed, the Ghadar Party is revered in India as an inspirational force in the long struggle for independence.

Ogden likens the Ghadar Party to the Black Panther Party, the small, militant group that inspired African-Americans and others, more because of what they stood for than their concrete achievements.

Thanks to Ogden’s five years of research, people are rediscovering Oregon’s role in India’s early liberation struggle, and the long-forgotten community here that helped plant the seeds.

“It’s a huge part of our legacy,” Kaur says. “They were inspired by the American values to go make a run at freedom.”

Next month, Astoria will honor the centennial of the Ghadar Party’s formation with a two-day celebration, dedicating a plaque near the former Finnish Socialist Hall where the party was formally created.

Kaur and other local members of the Indian community plan to attend. She says it’s an inspiring tale to share with Indian children growing up here.

Un-welcome mat

Immigrants largely from the Punjab region of British-held India began arriving here after 1906, Ogden says, spurred by job opportunities and racist restrictions enacted in Canada and elsewhere where the Indians had settled. In 1907, several hundred white workers rioted against Indian and other Asian immigrants in Bellingham, Wash. Violent outbreaks against Indians spread to Vancouver, British Columbia, other Washington towns, and Alaska, Ogden says.

Immigrants largely from the Punjab region of British-held India began arriving here after 1906, Ogden says, spurred by job opportunities and racist restrictions enacted in Canada and elsewhere where the Indians had settled. In 1907, several hundred white workers rioted against Indian and other Asian immigrants in Bellingham, Wash. Violent outbreaks against Indians spread to Vancouver, British Columbia, other Washington towns, and Alaska, Ogden says.

Oregon, seemingly a safer haven, saw an influx of Punjabis in 1908, many of them fleeing violence elsewhere, she says. Many found jobs in mill towns along the Columbia River, from The Dalles to Portland to Astoria.

Community leaders here, including politicians and Harvey Scott, influential editor of The Oregonian newspaper, railed against the violence, she says, viewing the male newcomers from India as an important source of labor.

Then on March 24, 1910, 300 men moved on Punjabi workers in St. Johns, then an independent city north of Portland, ransacking their homes and beating and robbing the men. “Up until then,” Ogden says, “Oregon had been this fairly peaceable place.”

But something happened here that differed from past riots against the Punjabis.

“They were driven out of town at night, and went and got the D.A. and brought him back to town,” Ogden says. Victims pointed out their attackers in the presence of the Multnomah County district attorney, and a grand jury was empaneled to punish rioters. Some 190 subpoenas were issued, and the St. Johns mill owner that employed many of the Punjabi men rose to their defense.

Though there wound up being only one person convicted, the fight-back was a turning point for the Punjabi community here, Ogden says. New activist leaders emerged, including mill worker Sohan Singh Bhakna and labor contractor Kanshi Ram. The two men from St. Johns networked with Har Dyal, a Stanford professor who became the leading public face and voice of the movement, and with British Columbia activist and newspaper publisher G.D. Kumar. Kumar’s paper had called on the Sikhs in India to rise up against British rule. A relatively small religious community in India, Sikhs constituted a disproportionally large share of the Indian army and the settler communities in Oregon.

Plotting revolution in St. Johns

At a March 12, 1912, meeting at Ram’s house in St. Johns, activists formed the Hindustani Association of America, naming Bhakna as president and Ram as treasurer.

At a March 12, 1912, meeting at Ram’s house in St. Johns, activists formed the Hindustani Association of America, naming Bhakna as president and Ram as treasurer.

Two weeks later, when Dyal came to town, the movement took a crucial turn at a second meeting at Ram’s house. Workers overruled Dyal’s more timid proposal and approved a call for Indian workers to “gird their loins to liberate India and work on revolutionary lines.” They decided a new political party and press were needed, based in San Francisco. The seeds of Ghadar, roughly translated as “mutiny” or “uprising,” were sown.

With Bhakna and Ram playing key organizing roles, meetings were held among Punjabi workers in other mill towns — Bridal Veil, Linnton and Winans — involving more than 200 attendees, Ogden says.

Those laid the groundwork for the formal meeting on May 30, 1913, in Astoria, attended by delegates from the various Punjabi communities. It was there that the official program of the Ghadar Party and newspaper of the same name were proposed and approved, Ogden says.

From its beginnings in Oregon, the movement spread to chapters worldwide, and a weekly newspaper was produced in San Francisco in four languages: Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi and English.

The movement arose during a powerful worldwide upsurge of nationalism, Ogden notes. The Punjabis here, despite feeling the heat of oppression and racism, were still freer than back home, and inspired by the American story of overthrowing British imperialism by violent means.

The Ghadar Party united people of the Hindu, Muslim and Sikh faiths, and intellectuals like Dyal and workers in the mills.

Their strategy was simple, Ogden says. They wanted to inspire Ghadr, or mutiny, among Sikh troops, whose loyalty to the British had helped ward off a major rebellion in 1857.

“They were basically going to go convince the Sikh troops to turn their guns around,” Ogden says. “That was their military and political strategy.”

A year after the party’s founding, Britain became entangled in war with Germany, and supporters were urged to return home to fight. Hundreds from this area did, Ogden says, perhaps a higher share of the Oregon Punjabi population than any of the communities in British Columbia, Washington and California.

But the revolt was a failure, and most of the rebels were jailed or killed, she says.

Bhakna was imprisoned and sentenced to life, though he was freed in 1930 and went on to many more years of activism with the labor movement and Communist Party of India. Ram was tried and hung in 1915.

Dyal, threatened with deportation in the United States, left for Europe and recanted his revolutionary views.

They didn’t succeed, Ogden says, but they inspired others.

“I think it’s a good thing when people dare to dream,” she says.

9/11 attacks spurred research on Ghadar Party

Johanna “Jo” Ogden says her inspiration for devoting five years of unpaid work to the Ghadar Party story comes from the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center.

“When I saw those towers go down, you knew nothing good was going to come from it,” she says. People once viewed as neighbors would be seen as enemies, she predicted. “I was looking for a way to talk of that, how people become the ‘other.’ ”

She sought advice from Kambiz GhaneaBassiri, a Reed College professor who wrote “A History of Islam in America.” He suggested she look into the Sikhs in the Northwest and the Ghadar Party, something he knew little about but enough to know it was under-researched.

Even most Indian historians ignore Oregon’s role in the movement, saying it got started in San Francisco. Wikipedia makes no mention of Oregon in its references, though it cites the leadership role of Bhakna.

Ogden scoured the archives of the St. Johns and Astorian newspapers, and found references to Sikh wrestlers, the St. Johns riots and ensuing events. She found hundreds of names in phone directories of the day, made easier because Sikh men typically go by the surname Singh and Sikh women the surname Kaur.

Ogden unearthed an important party of history that was unknown before, says Oregon Historical Quarterly Editor Eliza Canty-Jones. It raises many contemporary issues, Canty-Jones says. “What does it mean to be an American? And to have self-rule?”

That issue of the journal sold out, and additional copies were printed.

Ogden, who went back to school mid-career to study history, still makes her living as a legal assistant because jobs as historians are hard to come by. But she won the Joel Palmer Award for 2013, an honor for the historical quarterly’s top article from the prior year. And a publisher has asked Ogden to turn her work into a book.

The folks in Astoria planned a two-day event built on her findings, and invited her to speak.

And Ogden was invited to speak next March in India, where she’ll travel for the first time.