As Sikhs of the Guru, we find ourselves multiply blessed. Wherever we might be, Guru Nanak Dev Ji showers blessings of infinite variety, more than we can estimate. Some blessings are relatively mundane – mild weather, a great work opportunity, a new car. Others are uncanny and leave us wondering.

As a Canadian, I have heard many times now how great it is that MP Lt. Col. Harjit Sajjan “has become the first Amritdhari Sikh to hold the position of Minister of Defence in a Cabinet since the Sikh Empire.” It is truly wonderful that a turbaned and bearded Sikh should be chosen for such a responsibility. Dhan Guru Nanak!

What I have not heard from any quarter is any hint of curiosity as to how this should happen. Are we just to take for granted that Canada has always been a place of enlightened Cabinet selections? Should be consider Canada a natural superstar in the constellation of nations, a place of cultural diversity without prejudice?

No, this is not our Canada.

Those who live here know that this country is today in the midst of an effort at conciliation with its 1.4 million Indigenous peoples, who have been cheated of their lands and oppressed for hundreds of years by European settlers [Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada website] Lt. Col. Sajjan’s Vancouver is itself home to the infamous saga of the Komagata Maru, whose 352 Sikh, Muslim and Hindu passengers sailing from Hong Kong in 1914, were not allowed by the government to disembark, but forced to return to India. At that time, British Columbia (B.C.), the large, westerly Canadian province of which Vancouver is the largest city, took away the immigration rights of Asians together with their right to vote.

So, Canada does not have an unblemished history as a liberal democracy. Having taken over this great land from its original inhabitants, Europeans feared themselves being overwhelmed by a wave of immigration from China, Japan and India, so they put up legal barriers. Those barriers and associated prejudice endured for generations.

Something must have happened to temper the blatant racism and xenophobia rampant in Canada, forces I have seen to still exist in a milder form in rural Canada, as well as in England and Germany. This is article is my humble perspective of how Canada became the blessed place it is today.

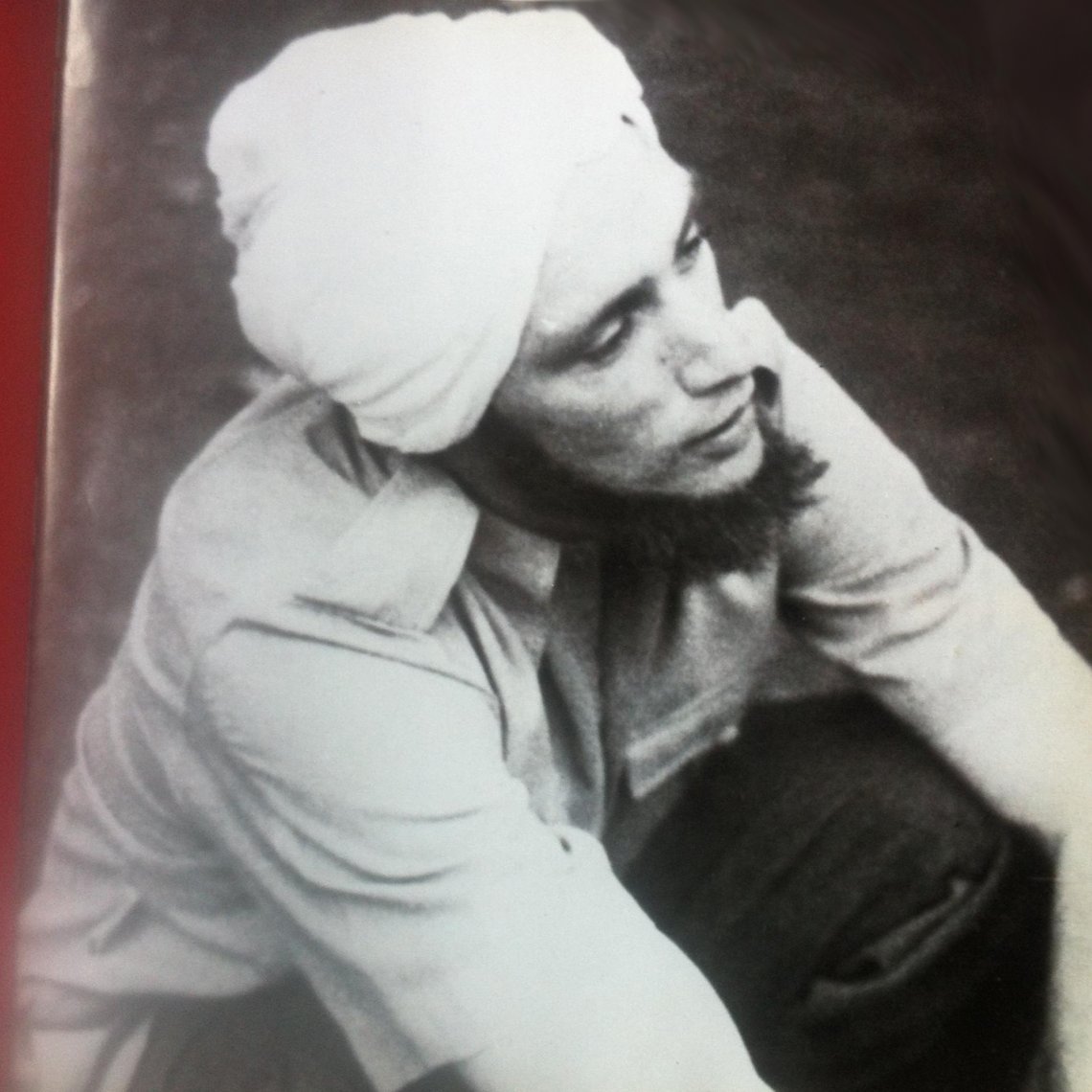

Some of the credit for Canada’s transformation from a racist, colonial backwater goes to Pierre Elliot Trudeau, its 15th Prime Minister (1968-79, 1980-84). Trudeau studied at some of the best universities (Harvard, Sorbonne, London School of Economics). As a young man, he trekked through the Middle East, India, and China. A funny thing: a striking photo of Trudeau during his adventure, published in his biographies, shows him with his beard grown out and hair under a respectable turban, looking like a regular Sikh [Sara Borins, Trudeau Albums, Toronto, ON: Penguin Books, 2000, 33]

Trudeau, father of Canada’s present Prime Minister, translated his cosmopolitan views into modern, inclusive policies - including multiculturalism and the encouragement of immigration from non-European countries.

Credit also goes to the hardiness and work ethic of immigrant Sikhs which made an impression everywhere they went. Author, Kamala Elizabeth Nayar describes in some detail their situation in B.C, where they first arrived in the late 1890s. She also depicts their efforts at sharing their culture in multi-cultural and sports events. Networking extended to unions and established political parties. [Kamala Elizabeth Nayar, The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004; Kamala Elizabeth Nayar, The Punjabis in British Columbia, Montreal QC & Kingston ON, 2012].

Sikhs did not arrive in Ontario until the early 1950s. There are today about 179,000 Sikhs in Ontario compared with British Columbia’s 201,000, so this describes a huge burst of population in Canada’s heartland.

As it happens, Ontario’s major cities of Toronto and Ottawa were at that time, and continue to be, blessed with a generally liberal atmosphere. There were several universities and many newspapers, particularly the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail, expressing a generous and thoughtful perspective. By the early 70s, the Sikh community in Ontario was still small, numbering less than 500, but some among them were educated, and they were not reluctant to press for their rights. In 1974, the Toronto Transit Commission was pressed to allow Sikh drivers to retain their beards and turbans.

Toronto also happened to be the Canadian bridgehead for the Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization (3HO) founded by Siri Singh Sahib Harbhajan Singh Khalsa Yogiji (Yogi Bhajan.) Started in 1970, the community was engaged in a constant campaign of challenging conventional thinking just by their existence as “white Sikhs.” By developing relationships with the media community, the local head, Gurutej Singh, ensured an on-going stream of print coverage. And why not? Yogi Bhajan’s students, the new Sikhs, raised all kinds of societal questions. Why did they become Sikhs? What was their critique of mainstream culture, anyway? It did not hurt that media guru Marshall McLuhan’s son, Michael, was for a time an avid companion of the group.

Papers, large and small, were soon educating their curious Caucasian readers (Ottawa and Toronto were overwhelmingly “palefaced” in those days) with such articles as “Spiritual Revolution” [Caitlin Kelly, The Varsity, October 8, 1975, 6-7], “He gave up materialism for meditation” [Helen Worthington, Toronto Star, November 14, 1975, E1], “Misfits of society turn to Sikhism,” [Sylvia Stead, Globe and Mail, August 9, 1975, 44], “Sikh way of life: Cold shower and meditation at 3:30 a.m.” [Sheila Ashcroft, Ottawa Citizen, October 14, 1975, 71]. The most widely read article of all was published in the national magazine, Maclean’s on April 19, 1977. Hubert de Santa’s “Healthy, Happy, Holy – and collectively wealthy and individually lethal” described the fastidious lives of the avid, new Sikhs from early rising to yoga and meditation, to reading from Siri Guru Granth Sahib, to work, and martial arts classes in the evening.

When prejudice reared its ugly head in Ontario with the arrival of new immigrants, Yogi Bhajan himself went to bat with the media. In “Sikhs keep ready to battle the bigot – to the bitter end” [Tom Hill, The Citizen, February 8, 1977, 33] the Siri Singh Sahib, students at his side, divulged, “It is not in our tradition to surrender.” Like our Punjabi sisters and brothers, we homegrown Sikhs also took on ignorance and bigotry. The media was happy to cover our escapades. “Turbaned Sikh wins right to be soldier” [Ron Lowman, Toronto Star, March 28, 1979] describes how Ek Ong Kar Singh Khalsa forced the Department of National Defence to bow to pressure from the Canadian Human Rights Commission to allow him to serve in a Toronto militia. “Razor Wars: Sikh blunts cutting edge of firm’s clean-shaven rule” [Dennis Robinson, Globe and Mail, May 10, 1980, 5] describes how another new Sikh successfully challenged a taxi company’s “no beards” rule at the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

There was a sweet irony in these cases. Not long before, we had been hippies. As flower children in our long hair and hippy clothes, we had challenged repressive social norms with our body politic, always risking arrest and a hair cut in jail for some minor misdemeanour. Now, with our hair in turbans, we challenged that same closed-minded authority and came away victorious by Guru Nanak’s grace.

It is my view that because of our unique situation, we new Sikhs were able to flip what might have been a case of cultural dissonance on its head. Whenever we came before a tribunal or a reporter, everyone involved knew intuitively that what was being argued was not actually the comparative merits of competing rights. We were arguing the irrefutable logic of the spiritual life coined by Guru Nanak: living healthy, happy and holy.

Then, in the 1980s, from a media point of view, we Sikhs lost our innocence. Tarred with the brush of “terrorism,” we learned who our true friends were. Mostly, the mainstream media was no longer with us, but when a particularly nasty act of defamation was published in a national magazine ([Ian Mulgrew, “The Sikhs in Canada,” Saturday Night, January 1988, 21-30], the resulting letters from Sikhs new and old, and from other Canadians were unanimous in condemning the article [“Very Clever, Mr. Mulgrew,” Saturday Night, April 1988, 5-6].

Over time, the real story of another Ghallughara in Punjab, in Delhi, in Kanpur, began to come out. Books like Soft Target (1989) and movies like Amu (2005) helped to shift the blame.

In the 1990s, Tapisher Singh launched a weekly television program “Insight into Sikhism” on one of the dedicated multicultural channels in Toronto. Taken up a few years later by Hari Nam Singh Khalsa, the popular program highlights many aspects of Sikh faith and practice to an English-speaking audience.

The election near Toronto of Gurbax Singh Malhi as the first turbaned Sikh MP in 1993 opened a new chapter in Sikh/Canadian relations. The subsequent election of Ujjal Dosanjh as Premier of B.C. in 2000 demonstrated both the effectiveness of Sikh political organization and the electability of Sikhs to high political office. Maclean’s marked the occasion with a cover feature “Sikh Power” profiling prominent Sikhs and focussing particularly on the volatile situation in B.C. [Jennifer Hunter, Chris Wood, John Nicol, February 21, 2000, Maclean’s, 18-26].

In the field of art and antiquities, in 2000, an exhibition of relics from the kingdom of Maharaja Ranjeet Singh showcased the splendour of the Sikh artistic heritage at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Haroon Siddiqui, editor emeritus of the city’s largest paper, marked the occasion with a touching elegy to Sikhs [“A great tribute to a great people,” Toronto Star, May 18, 2000].

Harnarayan Singh is known across the country for his avid play-by-play announcing in Punjabi of ice hockey games, Canada’s national pastime [Shanda Deziel, “Bonino! Bonino! Bonino! How a hockey man found his calling,” Macleans, April 9, 2016. Practically synonymous with the Toronto Raptors professional basketball club, Nav Bhatia actively uses the sport to promote intercultural respect and understanding. Cheering on the team from his courtside seat, and touring with them during the playoffs, Bhatia also buys 3,000 tickets to give to Sikh youth each year on Diwali and Baisakhi [Donnovan Bennett, “How Raptors Superfan Nav Bhatia used sports to acclimate to Canada,” Sportsnet, June 2, 2017].

While Kamal Nayar describes the perceived hostile attitude of Vancouver media toward Sikhs, the Toronto Star – managed according to a set of altruistic principles - has been effusive in its support, particularly during Baiskahi celebrations. Though other media may limit their coverage of the massive annual Nagar Keertan parade to city hall, the Star each year does an inspiring article embellished with big, colour photos. And the mainstream media still publish occasional, though increasingly rare, articles about new Sikhs [Sylvia Fraser, “Hari Nam Singh Khalsa… a nice Jewish boy,” Toronto Life, July 1998, 55-67; Raheel Raza, “White by birth, Sikh by Choice,” Toronto Star, April 11, 2009, G5]

Much media focus today is on Canadian Sikhs in the political sphere. More recent than MP Lt. Col. Harjit Sajjan’s becoming Defense Minister, has been the appointment of Palbinder Kaur Shergill as the first turbaned judge of Canada’s Supreme Court [Lien Yeung, “Sikhs celebrate B.C. woman’s ‘inspiring’ appointment as first turbaned judge in Canada,” CBC News, June 24, 2017] Moreover, Harjit Sajjan is not the only Sikh in the federal Cabinet. The others are: Navdeep Singh Bains (Innovation, Science and Economic Development), Bardish Chagger (Small Business and Tourism, Leader of the Government in the House of Commons), and Amarjeet Sohi (Infrastructure and Communities). The Cabinet of PM Justin Trudeau (Canada’s 23rd Prime Minister) is an image of diversity and respect. Half are women. It includes an Indigenous Justice Minister (who appointed Shergill), two Muslims (one born in Iran and one in Somalia), a quadriplegic Member and a Member who is visually impaired.

To add another element of amazement to the mix, the country’s social democratic party, the NDP is currently having a leadership race and among the four contenders is Jagmeet Singh, the turbaned and photogenic, former deputy leader of the Ontario wing of the party, whom some consider the candidate to beat [Lee Berthiaume, “Jagmeet Singh target of pointed attacks at latest NDP leadership debate,” The Star, June 11, 2017].

Enough said. Canada today is generally a great country to live in as a Sikh. But it could have turned out otherwise. Canada has a history of racism. The 1970s were marked by anti-Indian racism and during the 1980s, Sikhs carried much the same stigma attached to Muslims today, thanks to a concerted effort to defame the community. Somehow, things turned out for the best. We have Guru Nanak Dev ji to thank for this outcome.

There may be lessons for other minority communities to be learned from our experience in Canada. Here is a short list:

- Work hard and honestly.

- Find, create, and take advantage of opportunities to share the best of your culture and religion.

- Befriend the locals. Learn the language and culture. Don’t live in a social ghetto.

- Where possible, be a role model.

- Don’t be afraid to “own” the culture. Be a basketball “fanatic.” Get “obsessed” with ice hockey (or the local equivalent).

As an early Sikh in Toronto, I know we upended a lot of prejudices and preconceptions, just by being “white.” But our allegiance to health, happiness and holiness also struck a cord with many, many people we met and still meet.

Culture is a funny thing, especially when it is not a culture you subscribe to. It can be mean. It can be intimidating. But sometimes also, by Guru’s grace you can change that culture.