Saturday, August 23, 2014:His accent was strange, the turban even more so.

Saturday, August 23, 2014:His accent was strange, the turban even more so.

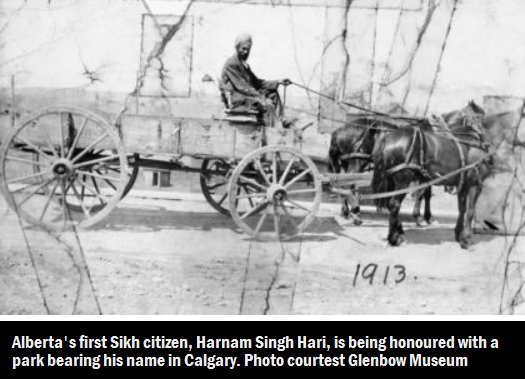

But when Harnam Singh Hari walked up to a pile of cement bags and hoisted a pair of the heavy sacks at once, that was all the introduction he needed — he got the job.

With most workers at the cement plant struggling to load just a single bag, the young Punjabi’s prodigious strength and a willingness to work made his unfamiliar dress and accent a moot point.

Hari had found his home — and Alberta in the year 1909 had found its first Sikh citizen.

“He was the first in Calgary, and likely the first in Alberta,” said Mona Hari Bartsoff, a great granddaughter of the pioneer.

This weekend, Singh Hari is finally getting some recognition for a daring rags-to-riches story even more daunting than most, with the dedication of a city park in his name.

Located in the southwest community of Kingsland, Singh Hari Park is on the very land the strapping ex-soldier eventually farmed, a 400-acre spread stretching from what is now Chinook Centre to Heritage Dr., between Macleod Tr. and Elbow Dr.

When he sold the hog operation to developers in 1956, Singh Hari was among Calgary’s richest citizens — a far cry from the penniless stowaway thrown off the train at Exshaw, where a cement plant had recently opened.

Just getting to that Alberta mountain town was a dream come true for Singh Hari, who’d heard glowing tales of Canada while serving with the British Army in Burma.

Married at 23 and with a young son in India, Singh Hari was convinced Canada was the place to build his family’s future — and though he faced an uphill struggle as a non-European immigrant, he was determined to follow his dream of farming.

Despite knowing he ultimately risked rejection at the Canadian border, Singh Hari left his family in India, first for Hong Kong and then a ship to San Francisco, where he managed to argue his way into America on the basis of past military service.

From there, he talked his way over the border into Vancouver (and likely paid, there being a large fee for non-whites at the time) where he worked a time for a menial wage at a sawmill before sneaking aboard the train to Alberta.

After his stint in Exshaw, Singh Hari landed a job tending the stables at Calgary’s Eau Claire sawmill, and with those small wages managed to buy a single pig, which he fed for free.

“Because he was so ingenious and made friends easily he was able to feed that one pig with food scraps from the CPR dining cars,” said Bartsoff.

Like John Ware before him, Singh Hari found the young city called Calgary didn’t really judge men on their skin colour or manner of dress — just their work ethic and dealings with others.

Some said he might have an easier time without the turban, but no one much bothered when he kept it.

“He never had problems,” said Bartsoff.

With his son Ojager joining him in 1919 (his wife didn’t follow until 1932, after more than 20 years separation), Singh Hari gradually built the hog-farming empire that would earn him the nickname “The Indian Emperor” among his Calgary peers.

It was a lucrative business, with contracts to supply meat during the wars — but Singh Hari was generous, and is also remembered for giving free ham to poor families in Calgary.

As the city expanded, the family moved south, and direct decedents of Calgary’s first Sikh citizens are still farming near High River.

For his family, the little park named for Harnam Singh Hari is a proud moment — a symbol of a dream fulfilled.

“We are really moved when you think of the courage it would take to leave his homeland, and come here with nothing,” said Bartsoff.

“He followed his dream and very few people manage to do that — he followed his love of farming.”