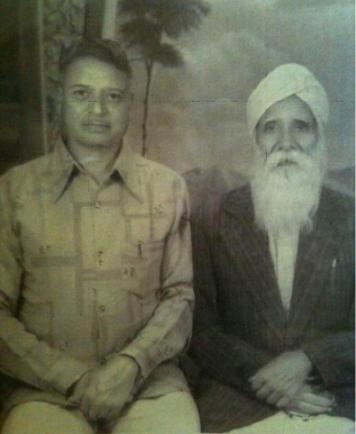

January 23, 2013: Bhajan Lal, my tabla teacher, was born in Lahore in 1935. One of three brothers, his father passed away before he completed the sixth grade, the grade in which he would end his formal education. He was twelve years old. Something else happened in his twelfth year: Indian independence, the formation of the Pakistani State, and thus partition, which would put his Lahori Hindu family in a predicament.

January 23, 2013: Bhajan Lal, my tabla teacher, was born in Lahore in 1935. One of three brothers, his father passed away before he completed the sixth grade, the grade in which he would end his formal education. He was twelve years old. Something else happened in his twelfth year: Indian independence, the formation of the Pakistani State, and thus partition, which would put his Lahori Hindu family in a predicament.

The poor planning, and irreverent drawing of the new border would split generations old communities. Mass hysteria pit village against village; Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims found themselves in bloody struggles for survival, each group playing antagonist and protagonist. Being Hindus on the Paksitani side of the new border, Bhajan Lal’s family made the dangerous trip, relocating to nearby Amritsar.

His family in financial need, Bhajan Lal took a job in an undergarment store where the tourist rest house (NRI Niwas) now sits near the Golden Temple. He did his best to work hard, but his heart was not in his work. He would go to work each day and did his duties, but his mind was elsewhere and all of his coworkers could tell. His mind was enchanted by sounds.

The sounds distracted him and teased him like the memory of a lover’s call. But the sound was not the call from a lover’s lips. The sound was the bouncing tones emanating from the stretched head of the tabla. In that time, the late 1940?s and 1950?s Amritsar was still a hub for musical expression and nowhere was it more on display than in the environment of the Golden Temple. Bhajan Lal would hear the music emanating from that place and see its purveyors in the grounds around the temple complex. He would go listen inside the temple itself. It was all he could think of. He had to join this world and become an artist himself.

Near his place of work, there were a few renowned tabla lutihers. Stores like Baba Heera Singh’s music shop, which still exist today, were near the old gothic style clock tower erected by the British residency seventy years earlier. It loomed like an eerie old tree. In that time, a set of tablas cost 25 rupees. Bhajan Lal made 20 rupees in a month. Upon receiving his monthly pay, he returned to the music shops and was able to bargain a table set down to 20 rupees.When he arrived home and his mother and grandfather saw that he had brought home drums instead of 20 rupees, they were livid. “We’re not musicians! Leave those tablas for the musicians at nautch (dancing girls) houses!” His grandfather was so incensed that he grabbed Bhajan Lal’s precious possessions and threw them out with the garbage. Undaunted, Bhajan Lal retrieved his instrument from the trash and brought them back home. Eventually his family would relent on the condition that the young man continue his work selling hosiery. He agreed to the terms.

While he continued working at the shop, he also began to practice tabla. He’d had some experience playing dholki, a simple two-sided drum, but nothing with the complexity of his new instrument. With such a small salary, Bhajan Lal was unable to pay a teacher, so he set out to learn table on his own-a difficult task due to the drums relative complexity and need for proper technique. He supplemented his hours of personal practice with tidbits of knowledge from rababi* masters he would have chance meetings with. His skill grew despite his lack of formal instruction to where he was accompanying musicians in many gurdwaras and Hindu mandirs in the city on a regular basis.Ustad Chhamta Parishad, the renowned master of the Benares Girana, dazzled onlookers. He was in Amritsar for a performance. His artistry in tabla was renowned and there were many people at the gathering. After he performed for some time, he sat, chatted, and drank tea with those in attendance. Young tabla players would approach and learn a short composition or touch his feet in respect. One young man’s style was peculiar as it contained pieces of the Rababi Girana, yet it was altogether its own style. The young man was self taught. Chhamta Parishad looked at the boy with joy; the boy had the spark in him to be a great shigird.

For twenty-five years, Bhajan Lal would travel between Varanasi and his home in Amritsar to learn from his master. Meanwhile, he started a family and had three sons. In turn, his sons’ appreciation for music would grow, and from time to time, they would study with their Mahan Ustad. By now Bhajan Lal was a fully accomplished artist and was accompanying great melodists and ragis, but his role as pupil was yet to end.

When Bhajan Lal met Ustad Rattan Singh, he was on his way to becoming a bona fide master in his own right. He had been a perfect student of Ustad Chhamta Parishad and was a renowned player in the Benares Girana. But Rattan Singh spoke to Bhajan Lal’s roots.Rattan Singh’s master was the renowned jorhi player Bhai Rakha Rababi of the Talwandi Rababi Girana, a style that dated back to the musical lineage of Bhai Mardana, Guru Nanak’s faithful travelling companion and musical accompanist. Traditionally Muslim, there was a vast musical lineage of Rababis that played the devotional Gurbani Kirtan of the Gurus throughout Punjab. With its message of pluralism and unity, the devotional poetry of the Gurus and the Bhagats of the Guru Granth Sahib was not restricted to any religion or creed to sing in Gurdvaras. In fact, until the early 20th century, half of the day of music at the Harimandir Sahib was reserved for the Rababis that had been traditionally associated with the Sikhs. As such, there was no requisite for the musicians to have been baptized as Khalsa in order to sing of the love of All.

It was from these very Rababis that Bhajan Lal learned his first compositions. In passing or in brief audiences, he would ask the Rababi tabla players for tips and things to play. When he received the honor of becoming Rattan Singh’s student, it was like returning home. He studied for fifteen years with his second master. His sons would join him more often as Rattan Singh was based near Amritsar in Tarn Taran. Rattan Singh treated the boys like grandchildren.

Bhajan Lal’s prowess was such that when Rattan Singh knew his time to pass was coming; he left all of his materials, notebooks full of compositions and notes on theory and history, to Bhajan Lal. Rattan Singh, as leader of the Talwandi Rababi Girana, handed that title to Bhajan Lal as Bhai Rakha had once given it to him.For the rest of his life, Bhajan Lal devoted himself to the life of a teacher. He taught hundreds of students, including his two sons; Hari Om and Murli Manohar. They are now both masters of the same tradition in their own right. They continue to teach and are a symbol of the pluralism that their lineage represents; from Bhai Rakha, a Muslim, to Rattan Singh, a Sikh, to Bhajan Lal, a Hindu, the legacy lives on through them and their many students. It is fascinating and inspiring to think that through the will and devotion of a fifteen-year-old boy, his family could become an integral part of a musical lineage that stretched back centuries to the feet of a spiritual master that helped enlighten the world.

Note: This article republished courtesy of Sikh Dharma Worldwide