|

Mohr-di-Hati: A True Sikh Enterprise I do not recall owner's exact name. Let's call him Mohar Singh. Mohr ran his father's grocery store in the main bazar of Haripur Hazara. Maharaja Ranjit Singh searched for a town to be named after his treasured General and Commander-in-Chief, Sardar Hari Singh Nalwa. Maharaja wished to honor Nalwa for his accomplishments. As a result, an area around the Fort of Hari Singh was designated and the Maharaja gave it the name of 'Haripur' in 1822. Since then, Haripur developed into a bustling town that also played a unique role in Sikh, Punjab and the sub-continent's history. The town is located in the North West region of Pakistan only a few miles from the famous Gurdwara Sri Panja Sahib. I was born there and finished my high school there. So you may see lot more written about this town elsewhere. This story is from my high school days before Indian sub-continent was partitioned. In the local lingo the grocery store was known as Mohr-di-Hati or sometime it was known as 'pansaari di dukaan'. Mohar was a humble and lovable person who was always found softly murmuring something that was not intelligible to others. He was actually reciting gurbani, either the nitnem or other hymns from the Guru Granth. He belonged to one of those Sehaj-dhari Sikh families who converted their first-born sons to khande-di-pahul_dhari khalsa Sikh. Such a practice was very common among the Potohari Sehajdhari Sikhs of Hazara. Mohar was the eldest son in his family. He was an interesting fellow and I often visited his shop to engage in conversation with him. One of those discussions, I recall, was about the stones or rocks he used as weights for the store's scales. Let me explain. In the days of my childhood, it was customary in our town for a shop keeper to sell grains, pulses, fruits, flour, etc. by weight. The goods were sold for 'x' annas (currency coins) per 'ser' (a weight measure, close to a kg) … just as we buy things here at so many dollars for pound, for example.

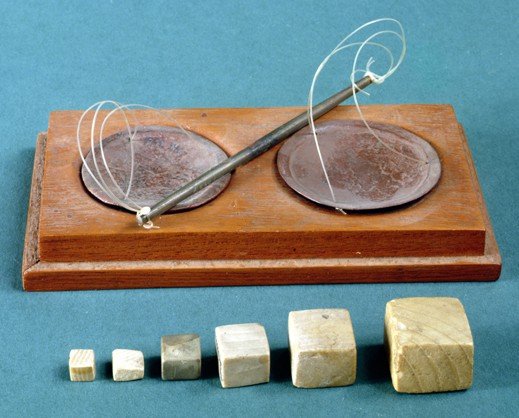

Mohar, like all who were in trade, plied the scales by holding it with one hand from a grip suspending the bar from its mid-point. The goods being weighed would be placed in one pan; the opposing pan would be loaded with rocks of various sizes until the bar achieved a horizontal position, indicating a balance between the loads of the two pans. Thus, a mid-sized rock, accompanied by two smaller ones, could achieve the required equilibrium. The metal weights with printed digits and letters to indicate their correct measure were available in the marketplace, but Mohar was not a rich merchant and therefore could not afford even the standard necessities. So he managed with stone weights of unverified values. And all the while, he would continue the muted murmuring that emanated from his lips. To any bystander today, Mohar's weights would automatically appear as tools for easy cheating; the contrived 'weights' could not be verified for accuracy. Mohar was far from having any plans for his weights checked by any worldly authority or apply any other measure of demonstrable honesty. But his integrity was never in question as it was guaranteed by his Sikhi. When asked about it, he would exhibit great confidence and consider the situation not at all unusual. A verse from the hymns of Guru Nanak was his certification of honesty. ਹਕੁ ਪਰਾਇਆ ਨਾਨਕਾ ਉਸੁ ਸੂਅਰ ਉਸੁ ਗਾਇ ॥ Whenever I recall talking to him about it, it became increasingly clear to me: when Mohar used the weighing rocks and continued to murmur gurbani silently, it provided him with an opportunity to practice and examine his Sikhi. He earned the confidence of his neighbors and thus increased his customer base. At the same time, he added to his neighbors' faith in Sikhi or the teachings of Guru Nanak. What a winner Sikh enterprise. For Mohar, the rocks had become the means by which the Guru talked to him as a Sikh. The same rocks were also means of disseminating Guru Nanak's teachings among his customers. Thus Mohar practiced Sikhi while living the life of an average person in this world, and used every opportunity to connect to the Creator. This was his format of Nam_Simran. (Earlier version of this story was published as http://sikhchic.com/people/mohar_singhs_true_measure) |

A crude, rusty set of scales - known as a 'tarakarhi or tarazu' - consisting of two pans suspended by strings, each from an opposing end of a wooden crossbar, served as a weighing appliance.

A crude, rusty set of scales - known as a 'tarakarhi or tarazu' - consisting of two pans suspended by strings, each from an opposing end of a wooden crossbar, served as a weighing appliance.