A shrine marks the spot where Guru Arjan died, a nadir for the community. Under Ranjit Singh, whose tomb is in the same complex, the Sikh Empire expanded.

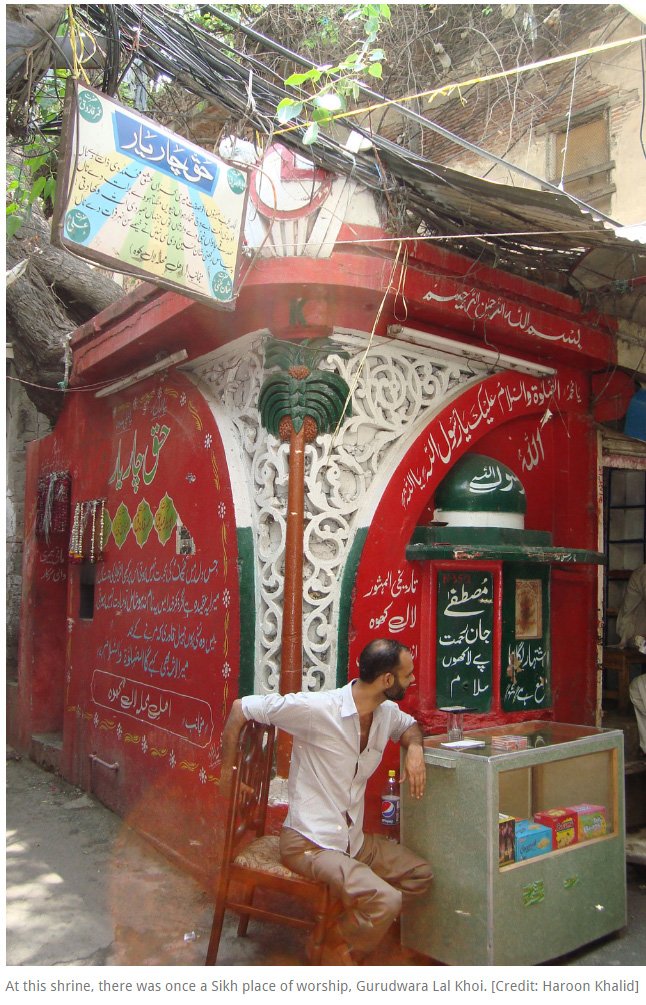

There is a small red structure inside the Mochi Gate of Lahore, one of the 13 historical gateways into the walled city. Painted red, the structure now hosts the shrine of Haq Char Yaar.

This shrine tells yet another tale of a place of worship belonging to another religion that was appropriated by the dominant Muslim population of the city after the creation of Pakistan.

I don’t know much about the history of the shrine, but the epithet Haq Char Yaar refers to the “four friends” in Islamic Sunni iconography – the closest companions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), all of whom later became Caliphs – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali.

Perhaps the clues to mystery of the origin of this shrine are contained within its name, which suggests that it does not belong to any one saint.

The two Gurus

Where this shrine stands today was once the site of a Sikh place of worship – Gurdwara Lal Khoi. The area within Mochi Gate retains the name Lal Khoi.

According to Sikh tradition, it was at this site that Guru Arjan, the fifth Guru of Sikhism, was tortured. The story goes that this site also hosted thehaveli, or mansion, of Chandu Shah, the diwan of the Mughal Emperor, who had developed a hatred for the Guru after he rejected a marriage proposal of the emperor's daughter with the Guru’s son, Hargobind.

Sikhs believe that it was at the behest of Shah, who was in connivance with Guru Arjan’s disgruntled elder brother Prithi Chand, that Mughal Emperor Jahangir, ordered the Guru’s assassination.

The Guru is believed to have spent his last days at this spot, occasionally washing and drinking from a well here – that’s how it came to be called Lal Khoi, the well of blood.

Guru Arjan’s assassination was a watershed event in the history of Sikhism. It changed the course of this community, similar to what the assassination of Imaam Hussain did for Muslims.

It was under Guru Arjan that the Sikh identity began to be solidified, distinct from that of the Muslims and Hindus. He began the compilation of what came to be known as the Guru Granth Sahib, giving the Sikhs their distinct holy book. He also completed Amrit Sar, the tank of nectar that was started by his father, around which the city of Amritsar developed, giving the Sikhs with their focal religious pilgrimage. Guru Arjan's death came as a major setback to the community, which had only just begun strengthening its identity.

Guru Arjan’s assassination was followed by a lot of introspection by the community, which feared extinction. Taking on the mighty Mughal Empire was out of the question. Should the Sikhs disavow all form of politics and emerge as a purely religious group?

This discussion was resolved by Guru Hargobind, the sixth Guru of Sikkhism and the son of Guru Arjan. On the July 24, 1606, Guru Hargobind emerged in front of his followers, dressed as a royal, wearing a turban with an aigrette on it, a sword hung on each side. He had taken the bold decision of militarising the Sikh community so they could defend themselves. The institution of the Guru and Sikhism were to take a new turn.

Two contrasting eras

The samadh of Guru Arjan, a modest structure, is also located in the city, facing the Lahore fort. Every year in June, hundreds of Sikhs, from all over, converge at this shrine to commemorate the martyrdom of their Guru.

It is a sombre affair, without the grandeur and pomp of the Guru Nanak Jayanti celebrations at the famous Nankana Sahib in Pakistan’s Punjab.

There is another small event in this complex at the end of June, this one to commemorate the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire, whose samadh stands next to that of Guru Arjan, and in strong contrast to it.

While Guru Arjan’s samadh is a modest structure, that of Maharaja Ranjit Singh is a triple-storey, regal memorial, elaborately decorated with frescoes of Hindu and Sikh iconography.

Separated only by a few days on a calendar, the two events represent two contrasting eras in Sikh history.

While the assassination of Guru Arjan in 1606 represents a nadir in Sikh history, a point when the community faced the threat of dispersion, their fortunes had turned by the time of the second death in the year 1839.

From 1799, the year he took control of Lahore, up until 1839, Ranjit Singh was the undisputed Maharaja of the entire Punjab, whose borders also included areas to west of Indus – an unprecedented tide of history, for invasion had always come from west to east.

Under Ranjit Singh, the Sikhs had completed an entire cycle. The militarisation that began after the death of Guru Arjan was at its peak. The Sikh Empire of Punjab and the Sindh served as the last bastion of an independent kingdom in a sub-continent that was now dominated by the British.

The Sikhs had earned themselves the title of a martial race by the time British took over Punjab after the death of Ranjit Singh. They were no longer a minor group, as during Jehangir’s reign.

The British knew that if they wanted to keep their empire intact, they would need the support of the Sikhs, which is what saved them during the war of 1857.

Haroon Khalid is the author of the books In Search of Shiva: A study of folk religious practices in Pakistan and A White Trail: A journey into the heart of Pakistan’s religious minorities