| THEBIGSTORY | |||||

|

younglives 'She can't spell her name' Nisha lived with her family in the servant quarters of the Lady Hardinge Hospital colony in cen- tral Delhi. A week ago, a child from the colony claimed he had seen Nisha with a man at a nearby bus ter- minal. He said he had identified her by a shirt that she wore very often.  Then three days ago, her sister's friend said he had seen her with a man in a market in south Delhi. Her parents are beside them- selves with grief. Earlier this year, another girl from the locality, a17- year-old, went missing and was found dead in a parking lot in south- ? Nisha, 16, went missing a month ago. Her brother Bittoo and mother Murti Devi are waiting for news about her. ARIJIT SEN/HT west Delhi. She had been sexually assaulted. "The police do nothing," said

Nisha's mother, wiping a lone tear

that rolled down her right cheek.

"Theyjust keep filing papers with

her name on them." C H E N N A I Waiting for a lead But Priya never learned of her results. She disappeared on the last day of her board exams. After she went missing, Sushila's husband began drinking heavily. Sushila had to keep the family going. So in between working as a tailor, she kept going to the local police and kept up the pressure. A few days ago, the police said they had got a lead. "We got several calls from a mobile number whose owner we've been trying to trace in relation to this case," said G Sasikala, sub- inspector at the police station. "We're going to question the owner. We are hopeful of tracing the girl." Sushila can only wait.

Two months ago, Mohd Azlan, a Class 10 student, went to school and never came back. Since then, his mother has spent most of her time staring at the door of her house in Yelahanka, a north- ern suburb of Bangalore. His father, Mohd Kalim Pasha, 38, who owns and runs a shop sell- ing mobile phones and accessories, is equally distraught. They first tried to track Azlan down on their own, visiting all of his friends' homes. When they did- n't make much headway, they approached the local police. The police merely told them to check with their relatives, the mother said. But eventually, they got the police to register a missing persons com- plaint and launch a search. In the meanwhile, a STD booth operator at the Yeshwantpur railway sta- tion in north Bangalore claimed he had seen Azlan and two other boys boarding a train, giving rise to speculation that he had planned to run away from home. "I can't digest that," said his father. "He never had a conflict with us." Mohd Kalim Pasha holds a picture of his son, Mohd Azlan, 15, who left for school two months ago and never returned. G V GIREESH/HT He was a good student, and between schoolwork and helping at the shop, he did not have much free time, his father added. His father has now approached the Society for Assistance to Children in Difficult Situations - Sathi for short - a non-profit group, to help him locate his son. "We fear the worst," said his

mother. "But I have confidence in

Allah; Gone in five minutes

Two years ago, Sheikh Azharuddin, 5, was playing at Karbala Maidan, a few min- utes away from his home in Howrah, north west of Kolkata, under the watchful eyes of his father, Sheikh Ainuddin. Ainuddin, 55, a rickshawpuller, left him playing at the ground and went back home for five minutes. By the time he returned, Azharuddin was nowhere to be seen. He lodged a missing person's complaint and met the superin- tendent of police in Howrah. For several months, the family did not hear from the police. Next, they visited Bhabani Bhavan, the headquarters of the criminal investigation department, but found no support. "We are still to get any news about our son," said Rukshna Begum, 52, Azhar's mother. - BIBHAS BHATTACHARYYA | ||||

| Three years ago, Sajda

Khatoon, 15, was gradually

replacing the contents of her

battered tin trunk. Over the

course of several months,

the teenager discarded her

dolls and toys to make room for nail polish and lipstick.

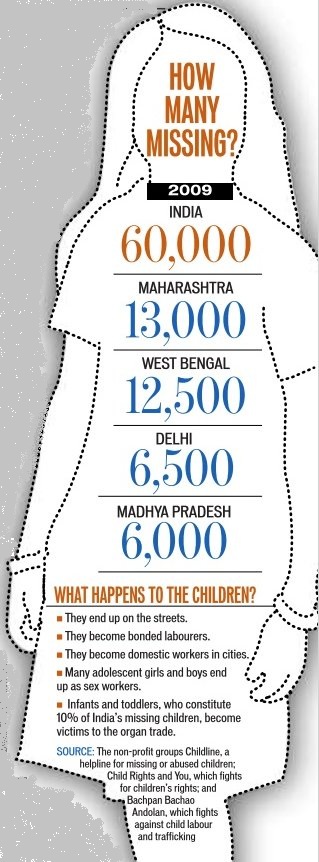

"Our little girl was growing up," said her father Salil Ahmed Khatoon, 60, who lives in a two-room house in a slum in Varanasi, where healso owns a darn- ing shop. "She was becoming a woman." Then one summer day Sajda vanished. She was home alone; her mother was away visiting her parents, while her father and her brother were at the shop. They returned in the evening to an empty house. All night, the family knocked on doors of neighbors in the slum and called relatives. But nobody had heard from Sajda. "I almost couldn't breathe that night," said Momina Khatoon, 55, her mother. Sajda is among thousands of Indian children who go missing every year. In Varanasi alone, 27 children went miss- ing in 2010, according to Guriya, alocal non-profit group that is a partner of Child Rights and You, a national NGO. More than 60,000 children were reported missing in India in 2009, a 35% increase from 44,000 in 2004, accord- ing to Bachpan Bachao Andolan, a Delhi- based non-profit group. (See 'How many missing?' on the right.) Also, only 40 per cent of these children are eventu- ally traced. Part of the problem is the police's handling of cases of missing children. When Sajda's mother, Momina went to the police to report her daughter missing, for instance, the police refused to file a first information report, or FIR. Instead, they merely made a station diary entry The police are duty-bound to investigate an FIR but not a station diary entry. (See 'What do the police do?' on the right.) Another problem is that the vast majority of missing children come from working-class families, who lack the networks and resources to help in an investigation. (They also lack the resources to closely supervise their chil- dren, which explains why more of them go missing in the first place.) Sajda's parents, for instance, hadjust one photograph of their daughter, a passport-sized one on her Class 8 report card showing a plump teenager with her hair neatly tied back in a ponytail. Momina was upset when the consta- bles at a police station in Jaitapura, a district in Varanasi, refused to investi- gate her complaint. "They said, 'She must be around. Don't worry'," Momina claimed. "My daughter could have been taken anywhere. How could I sit quiet?" Momina has every reason to worry. North-eastern Uttar Pradesh, with its porous 800-kilometre border with Nepal, is one of India's child-trafficking hot spots, according to a report on miss- ing children published last month by Child Rights and You. The big trafficking routes begin in Nepal and Bangladesh, go through India, and culminate in the Gulf states and European countries. For instance, girls from Nepal end up as sex-workers, boys from India end up in the Gulf states as riders in illegal camel races. About five lakh children under 18 are part of India's sex trade, according to the Child Rights and You report. (See 'What happens to them?' on the right.) Despite the police's indifference, Momina returned to the station every three days, forcing them to at least appear to do something. A constable slyly remarked to her that instead of looking for Sajda she should look for a young boy who had also disappeared around the same time, implying that Sajda had run away with him, Momina said. But nothing concrete happened, so Momina decided to do something herself. "I met every young boy's mother in the area. I interrogated all her friends," she said. "I wanted to leave no lead unex- plored." Three months later, with the help of Child Rights and You, the police rescued a thirteen-year-old girl, a native of a neighboring district in Varanasi, from a brothel in Mumbai and brought her back home. This girl said she had seen Sajda lying drugged on a couch in the same brothel. "I thought I'd found her," said Momina. She was wrong. Three months after this incident, the police finally filed an FIR about Sajda's disappearance. A year later, another relative claimed that he had spotted Sajda dancing with eunuchs at a fair in Delhi. The next day Momina travelled to Delhi and visited the fair. She also scoured the city's red light districts, showing everyone she could the lone photo of her daughter. For Momina, going to Delhi has now become an annual ritual. "I go back every year to the same fair to look for Sajda," she said. "I've made at least a hundred copies of her photograph." At home, Sajda's trunk lies just the way she left it three years ago; only, her nail paints have dried up, the bottles now sharing space with copies of letters that her parents have written to various authorities, including to Uttar Pradesh's chief minister Mayawati. Momina fears that the only photograph she has of Sajda will soon be of little help. "She must have grown up now," he father said. "She must look like her mother." On certain days, he is convinced that Sajda is dead. "I see her mangled body in my dreams," he said. "But on others, she comes and sings to me." Her mother nods her head. "She is alive. She is alive." |

BACHPAN BACHAO ANDOLAN

THIS DELHI-BASED NON-PROFIT IT RECEIVED responses from all states expect Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and some districts in Bihar. Therefore, the all-India figure is probably an underestimation. THESE NUMBERS include both first information reports (FIRs) as well as diary entries about missing children at police sta- tions. The police are duty-bound to act only on first information reports. THE WAY THE POLICE registers a case seems to be a function of the parent's socio-economic background: the more affluent the parent, the easier it is for them to register the case as an FIR. In rare instances, when the parents have evidence that the child was kidnapped, they are able register an FIR easily because kidnapping isacrime. NATIONAL CRIME RECORDS. THE POLICE USUALLY THE DELHI POLICE has set up a website, zipnet.gov.in, on which it puts up photographs and other details of missing children. THE NATIONAL HUMAN

RIGHTS COMMISSION | ||||