Kin Cheung/Associated Press

Pro-democracy activists held pictures of Liu Xiaobo in Hong Kong in 2009.

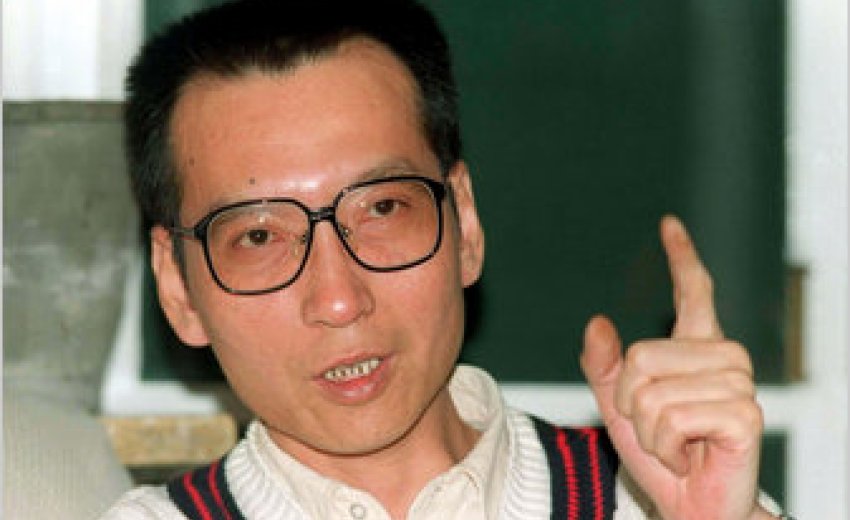

Oct. 8, 2010: BEIJING — Liu Xiaobo, an impassioned literary critic, political essayist and democracy advocate repeatedly jailed by the Chinese government for his writings, won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize on Friday in recognition of “his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

Mr. Liu, 54, perhaps China’s best known dissident, is currently serving an 11-year term on subversion charges.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry reacted angrily to the news, calling it a “blasphemy” to the Peace Prize and saying it would harm Norwegian-Chinese relations. “Liu Xiaobo is a criminal who has been sentenced by Chinese judicial departments for violating Chinese law,” it said in a statement.

Mr. Liu is the first Chinese citizen to win the Peace Prize and one of three laureates to have received it while in prison.

In awarding the prize to Mr. Liu, the Norwegian Nobel Committee delivered an unmistakable rebuke to Beijing’s authoritarian leaders at a time of growing intolerance for domestic dissent and spreading unease internationally over the muscular diplomacy that has accompanied China’s economic rise.

In a move that in retrospect may have been counterproductive, a senior Chinese official recently warned the Norwegian committee’s chairman that giving the prize to Mr. Liu would adversely affect relations between the two countries.

In their statement in Olso announcing the prize, the committee noted that China, now the world’s second-biggest economy, should be commended for lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and for broadening the scope of political participation. But they chastised the government for ignoring freedoms guaranteed in the Chinese Constitution.

“In practice, these freedoms have proved to be distinctly curtailed for China’s citizens,” the statement said, adding, “China’s new status must entail increased responsibility.”

News of the award was nowhere to be found on the country’s main Internet portals and a CNN broadcast from Oslo was blacked out throughout the evening.

Given that he has no access to a telephone, it was unlikely that Mr. Liu would immediately learn of the news, his wife, Liu Xia, said.

Given that he has no access to a telephone, it was unlikely that Mr. Liu would immediately learn of the news, his wife, Liu Xia, said.

Thorbjoern Jagland, the chairman of the five-member Nobel committee, said Mr. Liu Xiaobo had become the “foremost symbol” for the human rights struggle in China. While he acknowledged that China had sought to dissuade the committee from making the award to Mr. Liu, he underscored that the committee acted independently of the Norwegian government and believed that it was right to criticize big powers.

“The Norwegian Nobel Committee has long believed that there is a close connection between human rights and peace,” he added.

“China has become a big power in economic terms as well as political terms, and it is normal that big powers should be under criticism,” he said in Oslo, where the prize was announced. Last year, the committee awarded the peace prize to President Obama.

The prize is an enormous boost for China’s beleaguered reform movement and an affirmation of the two decades Mr. Liu has spent advocating peaceful political change in the face of unremitting hostility from the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

Blacklisted from academia and barred from publishing in China, Mr. Liu has been harassed and detained repeatedly since 1989, when he stepped into the drama playing out on Tiananmen Square by staging a hunger strike and then negotiating the peaceful retreat of student demonstrators as thousands of soldiers stood by with rifles at the ready.

“If not for the work of Liu and the others to broker a peaceful withdrawal from the square, Tiananmen Square would have been a field of blood on June 4,” said Gao Yu, a veteran journalist who was arrested in the hours before the tanks began moving through the city.

His most recent arrest in December of 2008 came a day before a reformist manifesto he helped craft began circulating on the Internet. The petition, entitled Charter ‘08, demanded that China’s rulers embrace human rights, judicial independence and the kind of political reform that would ultimately end the Communist Party’s monopoly on power.

“For all these years, Liu Xiaobo has persevered in telling the truth about China and because of this, for the fourth time, he has lost his personal freedom,” his wife, Liu Xia, said earlier this week.

Given his detention, it is unclear how Mr. Liu would take possession of the prize, which includes a gold medal, a diploma and the equivalent of $1.46 million.

The Nobel committee keeps its deliberations secret, but speculation that Mr. Liu would win was so intense and widespread that one Irish bookmaker refused to take any further bets last week and said it would pay out those who had already wagered on him.

Other contenders among a record 237 nominees included human rights advocates and public figures from Afghanistan, Myanmar and Zimbabwe.

After Friday’s announcement, the French government immediately urged China to free Mr. Liu, news reports said.

In London, Amnesty International said the award “can only make a real difference if it prompts more international pressure on China to release Liu, along with the numerous other prisoners of conscience languishing in Chinese jails for exercising their right to freedom of expression.”

Alan Cowell contributed reporting from London.