BOOK REVIEW:

|

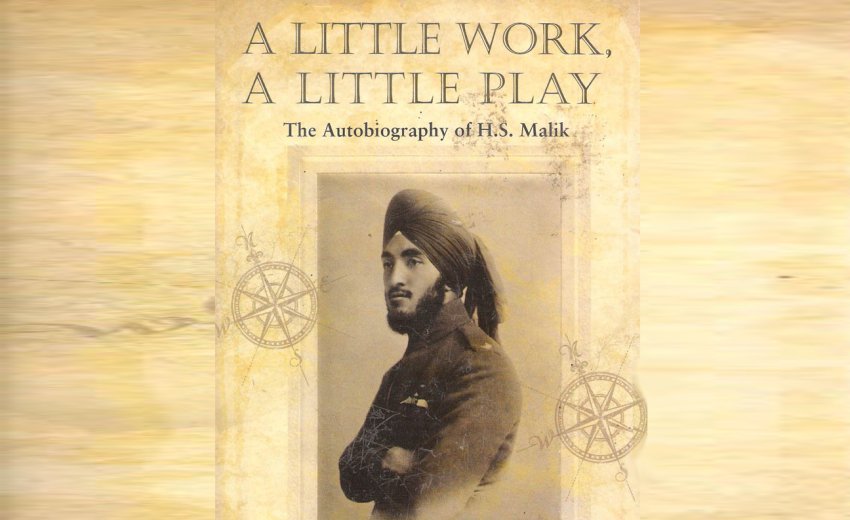

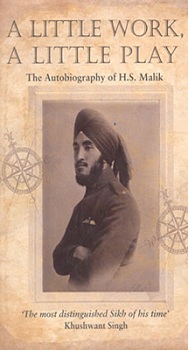

A LITTLE WORK, A LITTLE PLAY: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF H.S. MALIK. Introduction by Lester B. Pearson, late Prime Minister of Canada. Book Wise, India, 2011. Hard cover, Black & White photos, pp 296. Rs. 395.00, U.S. $24.00. ISBN #: 978-81-8733031-7 |

A Book Review by Dr. GURNAM SINGH BRARD

Sardar Hardit Singh Malik's autobiography, "A Little Work, A Litle Play " has been selected as sikhchic.com's BOOK OF THE MONTH for May 2011.

Not many of the present generation would know very much about Hardit Singh Malik. He was the most distinguished Sikh of his time, and had a remarkable career as a sportsman, civil servant and diplomat. He was born into a well-to-do Sikh family of Rawalpindi in 1894. After schooling in Pindi for a few years, he proceeded to England for further studies.

He was then only 14. When World War I broke out in 1919, he volunteered for service in the French Red Cross, and ran an ambulance from the war front to different hospitals in France. After two years he returned to England and joined the Royal Air Force, the first non-Brit with a turban and beard to become a fighter pilot. He took part in dogfights with German war planes over Germany and France.

His plane was riddled with hundreds of bullets, of which two pierced his legs. He crashlanded in France, and while doing so, broke his nose. After convalescing for many months in England hospitals, he was back in the battlefield. When the war ended, he joined Balliol College, Oxford. He played cricket and golf for the university.

As soon as he finished college, he was selected for the Indian Civil Service and posted to his home state. He returned home to India after 11 years abroad. He married the younger sister of his elder brother’s wife. Both girls came from a Hindu Arya Samaj family. Both turned devout Sikhs. In their homes, the days began and ended with recitations from Granth Sahib.

Malik served in many districts of Punjab before he was appointed Prime Minister of Patiala. He stayed in the post for three years till it was merged in Punjab in 1947. Pandit Nehru appointed him India’s first High Commissioner to Canada.

He stayed in Ottawa for three years before taking over as Ambassador of India to France. After a lifetime in service in India and abroad, he retired to his newly built home in New Delhi .

Malik had a passion for golf. He was seen at Delhi Golf Club every afternoon till almost the end of his life. He once expressed the wish to die on the golf course. That was not to be. He had a massive heart attack in 1984. A second attack in October, 1985, proved fatal.

Malik had no intention of writing his autobiography. He was persuaded by his wife and children to do so. It lay untouched for many years till his daughter Harji Malik took it upon herself to edit it and have it published. A Little Work, A Little Play: The autobiography of HS Malik (Book Wise) is now available in the market. It has an introduction by Pearson, who he befriended in Oxford, and who later became Prime Minister of Canada. It will be a source of inspiration to the present generation, specially to young sardars, who will learn how a person can be both devoutly religious and yet gain worldly success.

THE REVIEW

The book serves as a chronicle of the times from the Victorian era to the modern age.

The casual sounding title, ‘A Little Work, a Little Play,' may understate the importance of the book by Sardar Hardit Singh Malik, but it is consistent with his style of handling history-making events and people with natural ease and equanimity.

The book covers many decades of fascinating history, some of which he helped shape. The fact that he was a good sportsman in cricket, tennis and later on in golf, may have molded his character as much as the spiritual grounding did, as his family had emphasized discipline, honor and integrity as well as religious faith.

Being a good sportsman ‘opened a lot of doors' for him in early life and later provided him many opportunities to cultivate the friendships with princes, lords, kings, prime ministers, military leaders, and other world-famous, powerful and glamorous personalities.

In the book, Hardit Singh also recalls vividly, many of his interactions with ordinary people, showing his great humanity and his consideration all.

In the book, Hardit Singh also recalls vividly, many of his interactions with ordinary people, showing his great humanity and his consideration all.

My mind was transported to a very different time and environment as I read the description of his life of privilege in a prosperous family in Rawalpindi, Punjab, starting in the horse-and-carriage days of late 19th Century. I found it to be fascinating and informative. He mentions ‘a lavish house, good food, horses and carriages, servants galore and money' as well as private tutors, but incorporating religious devotion and convictions.

The British had conquered and started their rule in Punjab only 45 years before he was born, and he describes the interactions of his father with the British officials, and their attitudes in general toward the ‘inferior' subject races.

I enjoyed reading about his experience of travel to England at the age of 14 in the days when buses in London were still pulled by horses. He describes his attending the preparatory school, and then entrance into Eastbourne College, ‘a good public school', and other experiences in those times, including the All India Home Rule Movement.

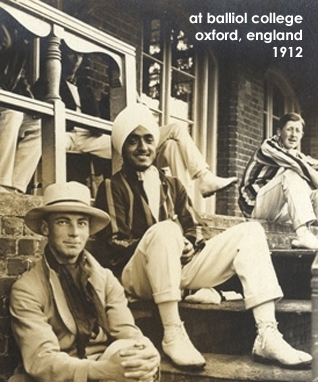

Later at Balliol College in Oxford, he developed many important friendships and contacts as he had done at Eastbourne; students who went to such schools in those days were the elites of society and attained positions of great power in their fields. Such contacts were helpful to Hardit Singh at some critical stages, such as when trying to enter the Royal Flying Corps.

The First World War started in 1914 and when Hardit Singh finished college in 1915, he wanted to play his part in the war effort. But the British military authorities could not accept an Indian as an officer in their forces. The best he could do was to join the French Red Cross, and he spent some memorable days in Cognac, France.

Then it seemed possible that he could join the French Air Force and based on that possibility, one of his influential friends shamed the British Air Force general into accepting Hardit Singh as an officer as the French were willing to do.

He served with great courage in the Royal Flying Corps as a fighter pilot.

In one combat mission, his airplane took 400 bullets, of which a couple pierced his leg. He was seriously wounded and after a crash-landing, he became unconscious because of loss of much blood. But after the War ended, a brilliant career in Indian Civil Service - once mainly the privilege of the British elite - became possible for him; every success after that became easy. It is a great credit to his convictions that he accomplished all this in a foreign country with beard and turban, starting in the days when attitudes were not so enlightened or tolerant as they are today.

As he describes the circumstances of his marriage to Parkash Kaur in the year 1919, it is quite revealing how Hindus and Sikhs comingled and inter-married, especially in the western part of Punjab, where some members of the same families became and remained Sikhs, while others would remain Hindus.

I learned many new things about the days when Hardit Singh became an Indian Civil Service (I.C.S.) officer, setting up new district headquarters in some small towns where the British administration was still taking shape, traveling through his territories on horse back, and dealing with superiors who were all British. Just as I expected, he states that although some of the British had foibles, eccentricities and prejudices, "the average Britisher in the I.C.S. was highly intelligent, well educated and hard working."

I learned many new things about the days when Hardit Singh became an Indian Civil Service (I.C.S.) officer, setting up new district headquarters in some small towns where the British administration was still taking shape, traveling through his territories on horse back, and dealing with superiors who were all British. Just as I expected, he states that although some of the British had foibles, eccentricities and prejudices, "the average Britisher in the I.C.S. was highly intelligent, well educated and hard working."

His appointment as Trade Commissioner in Europe in the early 1930s prepared him for the post of Trade Commissioner in the Americas in 1938. Just as he had a good friendship with Lord Berkeley (he could land his airplane in the latter's castle's grassy meadow) and later played golf with the likes of Duke of Windsor, General Eisenhower and King Leopold of Belgium in Europe, in America he played golf with the likes of Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Humphrey Bogart, partied with Greta Garbo, Joan Fontaine, Greer Garson, and had lunches with Aldous Huxley.

In the book, the reader will encounter some historically important events where the author made an impact. In 1947, when he was still the Prime Minister of the princely State of Patiala, he and a few prominent Sikhs met Jinnah, who offered the Sikhs some special rights and powers if they would join Pakistan. He was farsighted enough to reject the offer. As the first Ambassador (High Commissioner) of India to Canada, he was able to negotiate full citizenship rights for Sikhs and other Indians in Canada.

I am also impressed with the skills he used when he was Ambassador to France, in negotiating the release of French colonies in India (e.g., Pondicherry), the only case where no military force had to be used to regain territory in India.

He even did a stint as leader of the Indian delegation when the U.N. General Assembly was held in Paris.

The book, "A Little Work, a Little Play" depicts the exemplary character of Sardar Hardit Singh Malik with his attitude of friendship, goodwill, and fairness toward others, and full clarity of mind to obtain what is just. It is not only pleasurable to read, but also is a treasure house of information about the times past, in our Sikh and Indian society, as well as in the world. There is a generous index of references at the end.

[Courtesy: Sikh Foundation. Edited for sikhchic.com]