|

Le Golden Temple in Glorious Technicolour

Amongst our team we have come to believe that one is powerless to discover a hidden object unless it ‘wants’ to be found. As a diligent researcher, I have learnt to remain vigilant and ever hopeful for that incomparable moment of unexpected discovery. I regard myself as fortunate and privileged as some wonderful discoveries have presented themselves to me over the past two decades. The story of the most recent find begins, rather paradoxically, at the end of our latest book project ‘The Golden Temple of Amritsar: Reflections of the Past (1808-1959)‘. When the final phase of compiling this book was underway back in October 2009, we were sitting on a very healthy archive of over a thousand historic images of the Golden Temple. Amongst them, we had settled on the closing image: a lovely photograph taken by Tirlok Chand Jain in 1959 of a Nihang Singh, a warrior-priest and traditional protector of the shrine, standing guard over the Golden Temple.

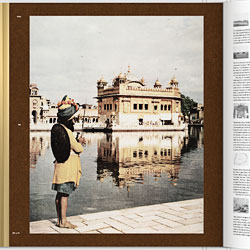

Our dedicated team of researchers had already spent thousands of days painstakingly tracking down early sepia-toned photographs, vivid watercolours and quaint woodblock engravings tucked away in collections around the world. Admittedly, this was ample material that could easily have given rise to several tomes on the temple, but being an obsessive sort (my mum once told me that she had been a voracious reader of history books when she was pregnant with me), I was hopeful that a final bit of digging might reveal a startling new discovery. I had no idea where to look but just knew I had to remain vigilant. Over two years later, and with the book finally published, my wish finally came true. Almost by pure chance, I discovered the earliest known true colour photographs of the Golden Temple. Remarkably, they dated from just before the First World War, which meant they were almost half a century older than Jain’s final image. Edwardians in Colour A little bit of online investigation revealed the collection in question to be that of the Musée Albert Kahn, a French national museum located in the suburbs of Paris that housed a unique historical record. Aptly titled the Archives of the Planet, it was one of the greatest collections of early colour photography and cinematography ever created.

The millionaire banker went on to initiate a twenty-two-year project (brought to an end by his ruin in the Great Depression) that saw him send a small army of photographers to every continent to capture the world and its peoples, not in black-and-white, but in true colour. The endeavour was made possible by the newly invented all-colour photography process called the Autochrome Lumière, a photographic revolution courtesy of the Lumière brothers, regarded among the earliest filmmakers in history. From 1909 to 1931, Kahn’s intrepid team of photographers captured an incredible 72,000 images (captured on fragile glass plates) and 183,000 metres of film of life in more than fifty countries. Many were taken during moments of profound upheaval, when age-old cultures were on the brink of being changed forever by war and the march of twentieth-century globalisation. Included in this astounding body of work are photographs from behind the lines of battle in the First World War and of the collapse of both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. While the thought of being able to see the world as it was a hundred years ago in authentic colour was incredibly exciting stuff, the big question that I needed answering was whether India, and indeed Amritsar, were on the project’s itinerary.

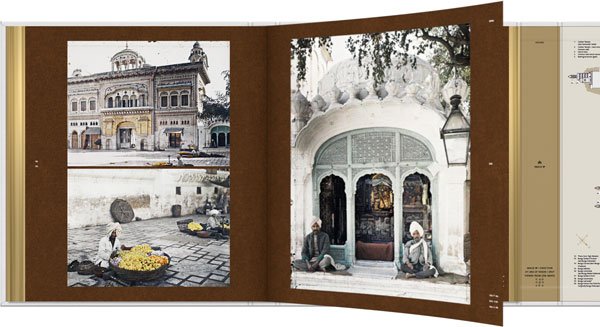

Seduced by the splendour of the architecture, and appalled by the squalor of daily living, the Frenchman documented portraits of locals and their environs in Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Agra, Delhi and Lahore (now in Pakistan), all in glorious colour. The best was yet to come. I opened the images attached to the email and my jaw dropped. The object had found me. I was staring at a group of incredible colour photographs—they revealed that on 15 January 1914, Passet had entered the sacred precincts of the Golden Temple and got to work. As I dwelled on each extraordinary image, their significance slowly dawned on me. Given the wanton destruction of Sikh material heritage in modern times, these were possibly the only surviving studies of certain examples of vernacular Sikh artwork, craftsmanship and life from that period. To boot, I was probably the first Sikh to have laid eyes on them since they were taken by Passet nearly a century ago. Snapping the Golden Temple in Colour

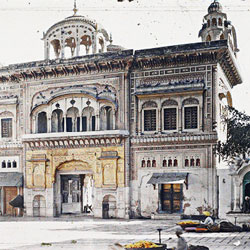

After removing his shoes outside and depositing any forbidden items such as cigarettes, Passet would have gained entry to the sacred complex. It appears he set up ‘base camp’ in the marbled forecourt that lay between two of the most important structures besides the Golden Temple; the Akal Takht (Immortal Throne) and the Darshani Deohri (Gate of Vision—more on this later). Shot 1 – The Sacred Bungalow

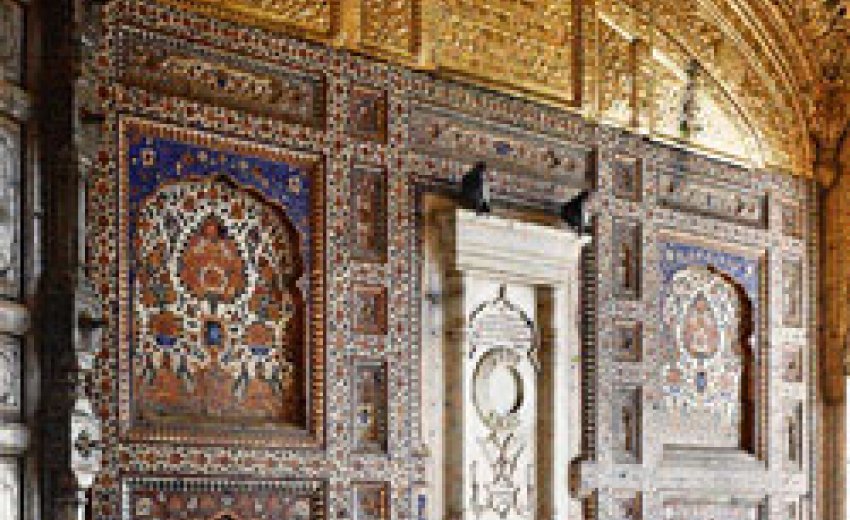

While the bungalow still stands to this day, its beautifully rendered interior wall paintings—which Passet’s snapshot reveals to have included scenes of the Sikh Gurus, a prince paying homage to his (spiritual?) master, and Vishnu’s man-lion incarnation tearing apart a deserving victim—are no longer visible. Presumably these were whitewashed over by disapproving caretakers during the Gurdwara reform movement of the 1920s.

It also served as the repository for the all-important temple records and ceremonial artefacts. One of the most fascinating artefacts that would be housed here was a gift made in 1925 by Fakir Haji Muhammad Miskin. This Muslim devotee spent nearly six years meticulously crafting a unique flywhisk made from 145,000 sandalwood threads—a true labour of love.

From examining his photograph, I think it’s safe to say that he was completely enamoured by the resplendent sight that presented itself: delightfully intricate floral murals with more than a hint of European influence and an arched ceiling literally caked with dazzling gilt-copper panels, profusely embedded with precious stones. At that time, over three hundred different patterns painted by numerous renowned artists could be seen on the walls in and around the Golden Temple; such was their quality that from a distance they resembled hanging Persian carpets. Sadly, the loss of these murals started at the close of the nineteenth century when devotees were permitted to present contributions in the form of inlaid marble slabs. These were fixed on walls painted with frescoes. Maybe to give balance to his composition, Passet’s lens focuses on a specially commissioned marble tablet let into the centre of the wall that commemorates an occasion when troops of the 35th Sikhs performed ceremonial ablutions in the sacred tank. Shot 4 – Mustard and Marigold

Thoroughly warmed up, Passet next headed off in search of the best vantage point for his long-shot of the temple. Meandering past the majestic hospices (bungas) erected by the Sikh nobility to serve as both dwellings for pilgrims and centres of classical learning, the Frenchman’s team of coolies, lugging his optical paraphernalia along the pavement, would no doubt have attracted the attention of passing devotees, warrior-priests and temple officials. Passet eventually settled on a spot in the south-eastern corner of the precinct.

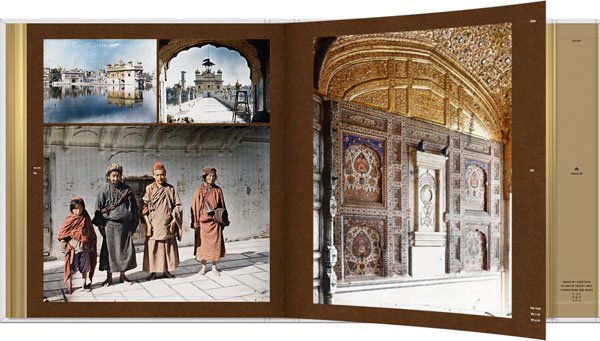

Shot 5 – Across the Cool Waters

‘Zoned in dazzling white,’ said fellow Frenchman, Baron Jean Pellenc, of this scene in 1933, ‘the water of the tank is blue beyond description, and in the midst glitters a marble islet crowned with a peerless diadem of gold.’ A century earlier, the following description of the holy site was published in a French newspaper, ‘Le Magasin Pittoresque’: ‘Everyone subscribing to this creed devotes himself with dedication and fervour, and as often as possible, to bathing in the Lake of Immortality (Amritsar). Day and night a huge crowd mills around this sacred enclosure, and it has never been known for any Sikh to abandon his pilgrimage through the threat of danger, however imminent.’ I couldn’t have said it better myself. Shot 6 – Elegant Archway, Marble Causeway

Looming large behind the shrine is one of a pair of watchtowers raised by the renowned Sikh warrior, Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, in the eighteenth century. It once sported a dome, but this collapsed almost a decade before Passet’s visit when an earthquake in Kangra reverberated across northern India. Possibly in a hurry, or perhaps keen to reflect everyday reality, Passet has included within his composition a workman taking a siesta opposite his stepladder.

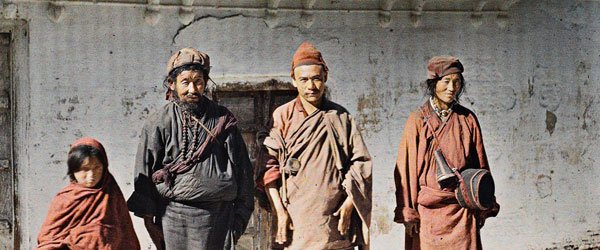

Somewhere along the precinct, underneath the balcony of one of the bungas, he took two photographs (he had to retake the first due to motion blur) of a group of Tibetan Buddhists, possibly a family. Their presence in Amritsar pays homage to two of Asia’s greatest spiritual personalities: the Buddha, who was said to have meditated at the original site of the Golden Temple over two millennia ago, and Guru Nanak, who visited Tibet on one of his great odysseys in the sixteenth century and is still honoured by the honorific ‘Lama’ in the region. The photographs serve to remind us of a time when the Golden Temple was wonderfully cosmopolitan in nature, truly reflecting the universal teachings of the Sikh Gurus and the Hindu and Muslim mystics whose divine poetry is included within the Adi Guru Granth Sahib. Passet’s Indian tour ended on 31 January 1914 and he returned to Paris with his Eastern treasure for presentation to his eager patron. Kahn’s interest in India and the Sikhs, however, wasn’t over yet. But that’s another, equally incredible, story for another day. Learn More

Parmjit Singh is the author of several books on Sikh history including ‘Warrior Saints: Three Centuries of the Sikh Military Tradition’, ‘“Sicques, Tigers, or Thieves”: Eyewitness Accounts of the Sikhs (1606-1809)‘ and ‘In The Master’s Presence: The Sikhs of Hazoor Sahib’. He is currently working on a special edition of ‘Warrior Saints’, due to be published in 2012. He is also a founding director of Kashi House, a not-for-profit social enterprise that produces illuminating resources on the culture and heritage of Punjab and the Sikhs. |