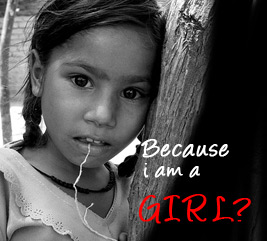

06 Apr 2011: Many Western observers hope that India's growth as a global power will both balance China's rise and ensure that rise remains peaceful. Indeed, the U.S. has identified India as a crucial partner for the coming century, and as part of its effort to cultivate a strategic partnership with New Delhi, Washington has even pledged to help India develop its nuclear energy capabilities. But the continued disappearance of India's women and girls described in preliminary census figures released last week is putting the future of India's security partnership with the West at risk.

06 Apr 2011: Many Western observers hope that India's growth as a global power will both balance China's rise and ensure that rise remains peaceful. Indeed, the U.S. has identified India as a crucial partner for the coming century, and as part of its effort to cultivate a strategic partnership with New Delhi, Washington has even pledged to help India develop its nuclear energy capabilities. But the continued disappearance of India's women and girls described in preliminary census figures released last week is putting the future of India's security partnership with the West at risk.

According to the census figures, the sex ratio of children ages 0-6 is now 914 girls per 1,000 boys, or 109.4 boys for every 100 girls. This sex ratio is the worst in the recorded history of the modern Indian state. In 1991, the 0-6 sex ratio was 934 girls to 1,000 boys, and when it further fell to 927 in the 2001 census, New Delhi launched a round of policy initiatives designed to turn the situation around.

Cradle baby schemes, where girl babies can be left anonymously at government buildings, were instituted in some states. In the north and northwest, where the worst sex ratios were found, state governments paid cash to families that chose to keep their girls and offered additional money if the girls were immunized, sent to school and not married off before age 18. In 2006, the first arrest was made of a doctor charged under anti-sex-selective abortion laws. Government officials have condemned the culling of daughters from the population, as have religious leaders. Some Sikh and Hindu priests have even administered oaths to their followers not to engage in this practice.

Whatever success these efforts may have had, they are apparently not enough. Indeed, as the average family size drops in India, the preference for sons only intensifies. It is sons who inherit land, pass on the family name, financially provide for parents in old age and perform rituals for deceased parents. Daughters, on the other hand, will cost the family dearly when it is time for them to be married, with a dowry at times costing as much as a family makes in a year. For all of these reasons, as families choose to have fewer children, they try to ensure the presence of a sufficient number of sons -- and as few daughters as possible.

As a result, having two X chromosomes becomes tantamount to having a serious birth defect in the minds of Indian parents, with genuine sentiment for their daughters giving way to a stifling economic calculus. Economists have often suggested that as daughters become rarer, they will become more valued. But dowry costs in India are rising, not falling, and the ratio of girls to boys continues to fall dramatically. In the area dubbed the "Bermuda Triangle for girls" in India, some districts register only 774 little girls for every 1,000 boys, a ratio of almost 130 boys to every 100 girls.

India, of course, is not the only country in Asia with severely disproportionate sex ratios. China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Pakistan, Afghanistan and others all have skewed ratios. Expatriate communities, such as Indian emigrants to the United States, also exhibit similarly imbalanced birth sex ratios. (It is worth noting that abortion for reasons of sex selection is not illegal in the United States, while it is strictly illegal in India, China and elsewhere.)

And yet, India is being portrayed as Asia's great hope, and as the major partner of the United States in that region. This is shortsighted, given that in March 2010, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated that "the subjugation of women is a direct threat to the security of the United States." In fact, there is ample empirical evidence that the security of states is closely linked to the security of women. If Clinton is right, then shouldn't India's dismal female-to-male ratio raise a red flag for American foreign policy?

It is time for the U.S. to raise the issue of India's sex ratio at the highest levels of diplomatic communication with government officials in New Delhi. The most important interventions India could make are improving the economic situation of women and providing a real old-age pension for families that choose to raise daughters. Regarding the first objective, enforcement of land and property rights for women would go a long way toward erasing the idea that daughters are economically unproductive. Old age pensions for families with daughters would then complete that circle, tangibly demonstrating that an investment in girls pays off not just for the larger society, but first and foremost for her natal family. It's also time for U.S. diplomats to ask why so few physicians have been tried under India's laws making sex-selective abortion illegal. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) gives the international community the right to hold India accountable for the enforcement, or lack of enforcement, of its laws in this regard.

It is time for the U.S. to raise the issue of India's sex ratio at the highest levels of diplomatic communication with government officials in New Delhi. The most important interventions India could make are improving the economic situation of women and providing a real old-age pension for families that choose to raise daughters. Regarding the first objective, enforcement of land and property rights for women would go a long way toward erasing the idea that daughters are economically unproductive. Old age pensions for families with daughters would then complete that circle, tangibly demonstrating that an investment in girls pays off not just for the larger society, but first and foremost for her natal family. It's also time for U.S. diplomats to ask why so few physicians have been tried under India's laws making sex-selective abortion illegal. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) gives the international community the right to hold India accountable for the enforcement, or lack of enforcement, of its laws in this regard.

Make no mistake, India's future will not be brighter for having sunk to 914 girls per 1,000 boys. The daughter deficit will create a society that is much less stable and much more volatile than it would be with a more balanced ratio. The sustainability of peace and stability -- for India and the region -- will be progressively undermined in lockstep with the devaluation of India's daughters.

Can we really call India, or any nation, a strategic partner when being female is devalued to this extreme point?

Valerie M. Hudson is professor of political science at Brigham Young University, where her research foci include foreign policy analysis, security studies, gender and international relations, and methodology. Hudson was named to the list of Foreign Policy magazine's Top 100 Global Thinkers for 2009, and she is one of the principal investigators of the WomanStats Project, which includes the largest compilation of data on the status of women in the world today.