|

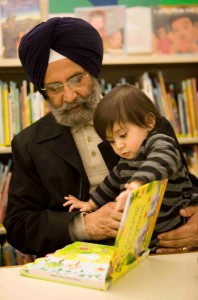

| My father reading to my daughter |

I don’t know if telling stories is part of the DNA of Punjabis, but virtually every member of my immediate and extended family can spin a good yarn. From the educated to the uneducated, city folk to rural farming stock, all of them can take a mundane story and turn it into the most entertaining story filled with all of the elements I spent my college years analyzing: plot, complex characters, simple characters, subtext, dramatization, personification, some even had the “O-Henry” ending (the one with the surprise twist at the end).

While the good ole chugli maaring factory a.k.a. gossiping that both men and women take part in anywhere Punjabis congregate – under the diminishing bohr tree, by the tube well, at a mela, at the langar hall, to name a few places – is wildly entertaining, I have always been much more fascinated by Punjabi folktales that my parents used to tell me on Sunday mornings in bed, or just before me and my sister went to sleep at night.

Some of my earliest memories that I can recall with clarity are of my mum and dad telling me the unadulterated story of the sparrow and the crow (ik si chirri, te ik si kaan), which many of you may be familiar with.

The story I remember revolved around the last two lines, which me and my sister gleefully waited for. Chirri: “Cheen, cheen mera poonja sarriya.” Kaan: “Kyon paraya khichar khaada?” which translates horribly in any language other than Punjabi, but here it is. Sparrow: “Ouch. Ouch. My tail has been burnt.” Kaan: “Why did you eat more than your share of khichari?” I warned you, didn’t I? This original version has its various story layers intact and an adult can easily pick up on the underlying theme of caste injustice, power, and from a narrative structural perspective: the structure of the cumulative folktale. But once sanitation starts taking place, these other interpretations often cease to exist. In a nutshell, here is the plot of the story stripped of its language, culture, and all entertainment characteristics:

Once upon a time, there was a chirri (sparrow) and a kaan (crow). They got together and decided they were going to make khichari. The sparrow went to get the rice and the crow flew off to get the daal. When the khichari was made, the sparrow told the crow he was dirty and should go wash himself in the pond before sitting down to eat. In the meantime, the sparrow eats up all the khichari and puts a lid on the pot. The crow returns and is furious that the khichari is all gone and sees the sparrow’s tail from behind a curtain (this was my mum’s addition). The crow takes a needle and heats it up on the stove and pokes it into the sparrow’s bottom, resulting in the above lines. Sometimes, they would tell a slightly tamer version where the sparrow’s tail was set on fire or a pot of boiling water was placed under her feathers. But every version resulted in the above rhythmic lines.

Not to delve too deep into semantics, but the word “folktale” connotes many different ideas, especially in the subcontinent. Some people use the word kahani, or story, for narratives that are meant for both entertainment and moral. The word is sometimes even used for religious based stories such as the Mahabarat, or Janam Sakhis, for example. Some put ballads and poems (like Heer-Ranjha) in the same category as a narrative folktale.

Like most folktales, the aim is not to entertain children, but to preserve a culture, its societal mores, and its language. The original folktale of Cinderella made popular by the Grimm Brothers, for example, is very different from the distilled children’s story we all know today. In the folktale, the stepsisters are not physically ugly, and in the famous scene of trying on the glass slipper Cinderella left behind at the prince’s ball, they desperately want it to fit, and in a horrific act, they cut off their toes and heels in order to squeeze their bleeding feet into the glass slippers the prince brought over.

To make this a children’s story, Disney, for good reason, tidied up the story and drastically altered the scene with the stepsisters trying to fit into the glass slippers. They even made the stepsisters physically ugly (usually by making them overweight and having large noses). This successfully converted it to an untraumatic children’s story, but it did take this story away from its original intent: to preserve German folkloric culture and while the moral is still kind of there, it is very watered down, and almost too tidy of an ending. You can’t really return to the Disney version of Cinderella as an adult and interpret things much differently because it’s been stripped of anything potentially offensive. And this same thing is happening to Punjabi folktales: they are being stripped of their culture and into palatable children’s stories.

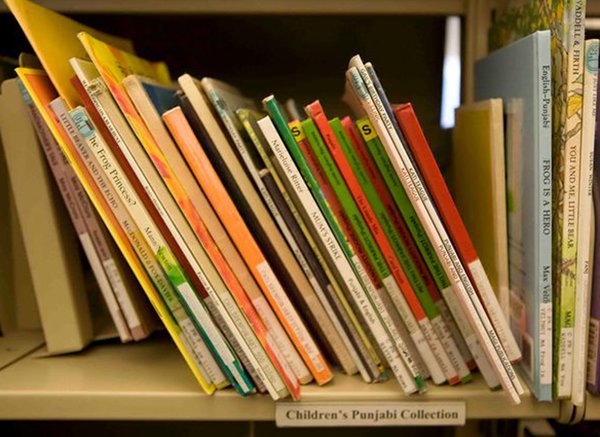

Last summer, I went to the Kerman Library in Central California (highly recommended) with my father, Pashaura Singh Dhillon, my wife, Sona Charaipotra, and our recently acquired daughter, Kavya Kaur Dhillon. The amount and caliber of adult fiction and non-fiction was impressive, but the children’s books . . . not so much. Kerman Library: Children's Books in Punjabi

If you notice the image above of the children’s shelf at the Kerman Library has several books in Punjabi, but not a single one has any connection to Punjab. On a side note, what’s with all the frog stories? As a relatively new papa (I’ve had this job for a little over a year), I am genuinely elated at the recent rise in children’s stories, particularly those with a multicultural perspective (check out a Lion’s Mane by Navjot Kaur), but I am appalled at how the books written in Punjabi have nothing to do with Punjab, are not being done in Punjab, but are translated English stories, and even names like “Shirly” and “Alan” are written out in Gurmukhi or Shahmukhi. Is it really that difficult to think of a Punjabi replacement name for Bob or Alan? I would even settle for Pinky and Tinky, even if they aren’t specifically Punjabi. And the few authentic Punjabi stories that are kid friendly have been so wildly sanitized, they bear very little resemblence to the original stories.

Above is an example of a Hindi version of the chirri te kaan story, which reverses the role of the protagonist and makes the dark skinned, conniving kaan, the baddie, who gets a lighted piece of wood thrown at him by the “chirriya” for stealing kheer that the vichari chirri was making for her “munna.” As the “kawa” (kaan, crow) runs out of the chirriya’s house, he utters the very poetic line: “Meri poonch jal gayi. Poonch jal gayi.” Moral of the story: if you are saving kheer for your munna, don’t let a dark skinned bird into your house or it will jock your kheer.

Years after I graduated college and having taken several graduate level courses in literature and one fascinating one on folklore, I started reading up on the chirri te kaan story and discovered there are many different variations of it all over the world, and many in India as well. There is a Marathi version of it which makes no qualms about it being about caste. In this version, the kaan is told he is dirty and tries to take a bath in the ganges, and is eventually burned alive. He is still the protagonist, but it makes the caste injustice much more prominent and as realistic an ending as you can get with a story about a sparrow and a crow.

My daughter is a bit over a year old now and on the verge of converting her babble to actual speech. She understands things like “nose” and “nak” being the same thing, and has mastered “No” and “nai.” Both of these inevitably end with her smacking me across the face, which I am hoping is an accident, even though it is followed by hysterical laughter every time it happens. I have grown up in many different countries and been exposed to other languages, some of which I still fluently speak. But even though I speak several languages, I have been reading up on raising bilingual children because quite frankly, I don’t know the science behind why I can seamlessly switch from one language to another.

This topic has been discussed a few times on TLH (here, here, and here), but it is still a debatable issue. Eventually I will teach Kavya her oora aera alongside her abcd, but I remember being bored out of my head learning the alphabet because, let’s face it, learning the alphabet and punctuation in any language is not fun. But it is important. What I’d like to instill in her is the intrinsic value of Punjabi folktales from yesterday and to realize that not only is the language hers, so is the culture, tradition, food, land, and, of course, the Sikh religion, which wasn’t imported from anywhere, and organically grew out of the Land of Five Rivers.

We obviously don’t want to traumatize anyone, children or fragile adults alike, with tales filled with excessive violence or explicit depictions of sex in the name of preserving the Punjabi folktale, but with the amount of violence on television, are they really going to be that traumatized by seeing a sparrow get its tail burnt, a wolf getting the contents of his stomach replaced with rocks and sown back up, or of a rich farmer sacking his farmhands and hiring a blue demon (a few other stories my mum and dad used to tell me)? And if they are deemed too violent or sexually explicit for children, where do these folktales go? Do they just fade away into obscurity when the storytellers die?

The only real difference between Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies were the body count. Shakespeare believed there was a very thin line between comedy and tragedy. A Shakespearean comedy ended, almost like a Bollywood film, in a marriage; a tragedy, on the other hand, ended in utter bloodshed. Would we still be reading Shakespeare if his plays like Merchant of Venice were tidied up for its anti-semitism, or Hamlet was less violent and he had a better relationship with his mother and step-father? How do you translate a sonnet with western metaphors into Punjabi (there are Punjabi versions of the Bard)?

What Punjabi folktales have you grown up with? Do they exist in books or other mediums? Are they still recognizable? What are your thoughts on censoring these stories to make them kid-friendly?