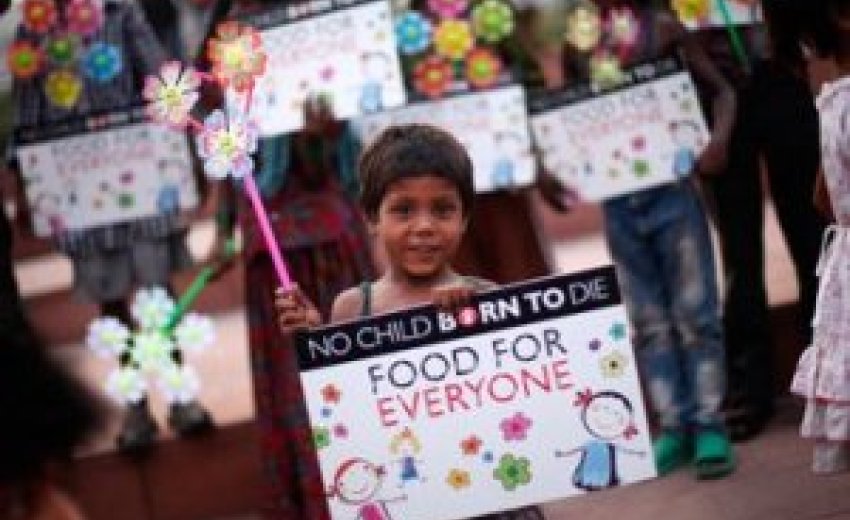

The leaders of the G8 must acknowledge the vital financial and symbolic role that tax justice has to play in tackling hunger

Sunday 9 June 2013: On one hand, ending hunger involves getting agriculture and nutrition policies right. But it is also about social justice, good governance, and the broader set of conditions within which targeted food strategies can work durably and for the poorest.

On the first count, things are looking positive. At Saturday's "nutrition for growth" summit in London, £2.7bn ($4.15 bn) was pledged for tackling under-nutrition up to 2020. This fresh funding will help to develop country-level nutrition plans and move forward a series of targeted interventions aimed at ensuring food with high nutritional value is made available to pregnant women and children.

While it is crucial to improve the nutritional content of food and supply it to those in need, these plans cannot and should not substitute efforts to address the root causes of hunger – namely the poverty, disempowerment and neglect of small farming communities worldwide.

The UK presidency of the G8 has a chance to tackle this side of the hunger coin in a week's time, when G8 leaders convene at Lough Erne on 17 June for a two-day meeting that will address the flagship issues of tax, trade and transparency.

In terms of tackling hunger, nothing is more crucial in financial or symbolic terms than tax justice. Combating hunger and malnutrition cannot be achieved through aid alone. It requires poor countries to invest in achieving local food security by rebuilding their own agricultural base and reducing poverty, both rural and urban. This means supporting farmers – who are themselves among the most food insecure – and investing in national social protection floors for all.

In essence, governments must be able to govern, ambitiously and coherently. To do so, they must be able to draw on enough of their own resources – alongside development aid – to put strategies in place that are holistic enough to fight hunger in all its complexity. Moreover, they must be able to take real ownership of these strategies.

The failure of companies and individuals to pay a fair share of tax has played a major role in unbalancing the books of major economies. A fairer contribution in the future is now crucial to rebuilding public spending capacity and alleviating the harshest cuts.

For developing countries not only is GDP significantly lower, but a much lower share of national income is collected in taxation – just 13% as opposed to an average of 35% in OECD countries (pdf). In many of the world's poorest nations, governance is crippled as a result.

Multinational companies that mine, farm and process the natural wealth of these countries are the major beneficiaries of this low governance capacity and the weak taxation it brings. Companies with global supply chains, and dizzying nets of subsidiaries in multiple tax jurisdictions, are able to navigate their way around tax systems that their own highly-paid accountants may know better than state authorities. Tax avoidance, often through "transfer pricing" within multinational groups, is the usual way of doing business.

By forgoing these tax revenues, developing countries critically undermine their own ability to build infrastructure, drive development and create jobs – therefore making themselves perpetually dependent on the inflow of foreign investment. Weak taxation and deregulation make it possible and profitable for multinationals to exploit farmland in the developing world in ways that undercut and marginalise local small-scale farmers, degrade the environment they rely on, and exacerbate hunger. And the taxes not collected from these companies become the funding shortfalls that prevent governments in the developing world from financing, owning and implementing the multi-year, multi-sector food security strategies that are proven to reduce hunger.

Aid flows continue to be vitally important, but can never compensate the loss of tax revenue. According to the OECD, money lost by developing countries to tax havens is nearly three times the amount of aid received, while recent figures from Global Financial Integrity (GFI) indicate that, for Africa, the ratio is as much as 17 to one. Thhis year's Africa Progress Report showed that no region has suffered more from tax evasion and the plundering of national wealth, which contribute to increased inequality even when the continent experiences economic growth.

It's not just the usual suspect tax havens that are culpable. The whole world is a tax haven for companies able to navigate between its tax jurisdictions. The G8 cannot control tax policy in developing countries, but it can clamp down on the multinationals and individuals whose wealth is often earned in developing countries but domiciled and managed in London, New York and Paris, perversely causing more cash to flow from poor countries to rich countries than vice versa.

In turn, developing countries should co-operate to stop the "race to the bottom" between them in order to attract foreign investment. Such competition has reduced their tax levels to a point where their capacity to govern, and to fund food security policies, is undermined – and this before the impacts of tax evasion and avoidance are taken into account. On taxation, we need less international competition and more international co-operation.

The G8 can make a difference on hunger. The hunger and tax agendas must be brought together. The relatively simpler part has been done, in the shape of fresh aid commitments at the nutrition for growth summit. Now, in Lough Erne, the G8 must treat tax injustice as the driver of hunger and poverty that it is, urgently initiating a new era of tax transparency.

This would pave the way for the world's poorest countries to play their part in the fight against hunger – the most complex part, which only they can perform – by taxing fairly, governing coherently, and putting their resources at the service not of elites or multinationals, but of their poorest citizens.

---------------------------------

Related Article:

London hunger summit yields $4bn commitment on child malnutrition

Mark Tran | The Guardian, UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2013/jun/08/london-hunger-summit-child-malnutrition

Annual funding set to double to $900m by 2020, helping 37 million children globally to fight malnutrition

Saturday 8 June 2013: Rich countries have secured commitments of up to $4.15bn to tackle malnutrition, in what was described as a "historic moment" in efforts to reduce the number of child deaths.

The commitments mean that funding on nutrition will effectively double from about $418m to about $900m a year between now and 2020. The UK has committed an additional £375m of core funding and £280m of matched funding in the next seven years, while the European commission will contribute €3.5bn between 2014 and 2020.

"It is more than we expected and it is evidence of a real surge in the last two weeks. The European commission coming in strongly was a real game changer," said Adrian Lovett, Europe executive director for ONE, the anti-poverty group.

....more

---------------------------------

Related Article:http://www.sikhnet.com/news/what-will-it-take-end-poverty-generationhttp://www.sikhnet.com/news/what-will-it-take-end-poverty-generation

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/un-panel-calls-end-extreme-poverty-2030-roadmap-worlds-top-challenges

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/battle-end-hunger-winnable