In 1908, Harnam Singh Hari resigned from military service and began to plan for his future abroad. Two years later, at the age of 27, he bid goodbye to his family and left for Canada via Hong Kong. It was a bold step, as immigration into Canada from British India was severely restricted.

In 1908, Harnam Singh Hari resigned from military service and began to plan for his future abroad. Two years later, at the age of 27, he bid goodbye to his family and left for Canada via Hong Kong. It was a bold step, as immigration into Canada from British India was severely restricted.

There was no knowing whether he would be allowed to disembark from the steamship that was to take him to Canada. Once in, there was also no telling when he would be able to return to his family, if at all. After six weeks he was finally on a steamship headed for San Francisco and had heard that his fate lay in the hands of William Hopkinson, an Anglo-Indian born of a Sikh mother and an English father.

Raised in India, Hopkinson had moved to Vancouver in 1908 and had been hired by both the Canadian and US Governments as Immigration Inspector and Interpreter. On arrival at San Francisco, Hopkinson came on board the ship and chose only four passengers as prospective immigrants. Singh was not among them.

Unwilling to go back without a fight, he decided to present his case to Hopkinson. He argued that he deserved special consideration for his military service, pulling out his army discharge papers to make his point. His impassioned plea had the desired effect, and he was accepted by Hopkinson as his fifth immigrant.

Once ashore in San Francisco, the five Sikhs who had been allowed in decided to split up. For Singh there was only one way and it led north to Vancouver. Although he had a professional qualification, he still had to take a low-paid menial job due to the employment restrictions placed upon Indian immigrants, and it is not surprising therefore that it was at a sawmill that Harnam Singh secured his first job where he worked for a year and a half before hearing that large tracts of farming land were available in neighbouring Alberta.

There was then no doubt in his mind that this was the place for him.

His journey east in 1910 to the town of Calgary was initially undertaken as a stowaway on a freight train, as he had no money to buy a ticket. En route, at Banff, he was discovered by the police and booted out. He now had no option but to walk the remaining 85 miles on foot, surviving by following the railway line and by feeding on leftovers tossed out by passengers.

Entering Calgary, he spotted another sawmill and asked for work and was eventually hired for the pitiful amount of 10 cents an hour. He stayed there for four months before he began to look around for another job.

Harnam Singh was the first Indo Canadian to set foot in Calgary. The uniqueness of his position was brought home to him when he went to look for a job at the Canadian Pacific Railways to unload cement bags from freight cars. He was politely told that the work would be too heavy for him and further advised to remove his turban and cut his hair to improve his employment prospects.

Family legend has it that without waiting to be asked, he lifted a 100 pound cement bag in each hand, and then unloaded the nearby freight car there and then in half the time it usually took. Needless to say, he was hired. Within a year, he had saved enough to rent a modest home with two and a half acres of land. He then began to investigate the possibility of breeding livestock as a business. This brought him in touch with a renowned local auctioneer, with whom he struck up a lifelong friendship and under whose advice he subsequently bought, bred and sold mainly cattle and hogs.

Harnam Singh’s frugal habits, coupled with his hard work and great business sense, helped him amass enough money to buy his own five-acre farm two years later. From then on, his land holdings and livestock business gradually grew so that whenever he attended an auction in Alberta, his auctioneer friend now introduced him as the “Indian Emperor” who could outbid anyone in the area. These were no idle words, as at one time Harnam Singh owned 5,000 acres of land on which much of the present city of Calgary is now built.

The city of Calgary recently honoured him by naming a park in his name on the very land the ex-soldier eventually farmed, a 400-acre spread stretching from what is now Chinook Centre – one of the city’s main shopping centres.

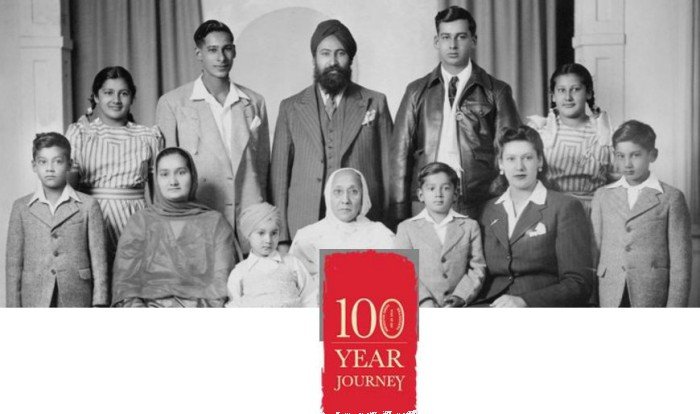

When he sold the hog operation to developers in 1956, Singh Hari was among Calgary’s richest citizens — a far cry from the penniless stowaway.

The direct decedents of Calgary’s first Sikh citizens are still farming near High River.