Three generations of Amar Singh’s family have helped keep the country safe for over 100 years as members of the police force.

Three generations of Amar Singh’s family have helped keep the country safe for over 100 years as members of the police force.

ISHAR Singh was fated to come to Malaya. “My father was set on going overseas after a soothsayer told him he would travel across the ocean. After hearing this, he would pester my grandparents to let him leave Punjab and seek a better life elsewhere. However, as he was the eldest son, they were reluctant to let him go,’’ recounts Ishar’s son and Kuala Lumpur deputy chief police officer, Senior Asst Comm Datuk Amar Singh.

Ishar was born in a farming community and life was tough. The soil was poor and the climate inhospitable. Ishar knew too that the family’s small plot of land would have to be further divided between him and his four brothers.

Ishar’s opportunity to leave came through a villager named Karnail Singh. He was already in the Malayan police force and had returned to his village of Moosa for a visit.

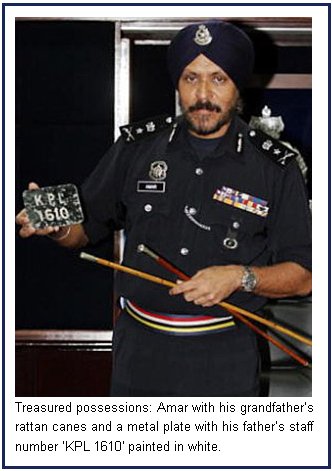

Treasured possessions: Amar with his grandfather’s rattan canes and a metal plate with his father’s staff number ‘KPL 1610? painted in white. Karnail Singh said he would recommend Ishar for a job in the police force.

“Both of them left Punjab for Malaya via Calcutta in 1938 when my father was 18 years old. My grandparents felt secure as Karnail said he would look after him. They gave my father 80 rupees and told him to not dishonour the family name and to return to Punjab if he didn’t make it in Malaya,” says Amar.

In those days, it was common for Sikhs to bring over others from their village. Like all Sikh recruits, Ishar was required to keep a turban as the British believed that it would ensure his loyalty to the government.

Ishar arrived in Penang and did odd jobs while waiting for an opportunity to join the police force. In 1939, he was accepted into the force and posted to Sitiawan, Perak, after undergoing training.

Amar’s memory of what his father did during the Second World War is hazy. During the Emergency, however, Ishar spent a large part of time in Papan, Perak, which was considered a hotbed for communist insurgents.

“My father said it was a terrifying experience going out on patrol as bullets would whizz past and he never knew if he would be ambushed or come back alive. He lost quite a number of his friends during that time,’’ recalls Karnail Singh, Ishar’s eldest son, named in honour of the man who brought the teen to Malaya.

Ishar was a pioneer member of the police jungle squad which was first established during the Emergency. Squad members would stay in the jungle for up to two months at a time and shift camp in pursuit of terrorists. Ishar retired as a corporal in the Federated Malay States Police (FMSP) in 1971. He worked as a security guard in the Kinta Omnibus workshop and passed away in 1999 at the age of 80.

Ishar never regretted his decision to join the force.

“My father really liked his job and took pride in what he did. To him, Malaya was a land of opportunity. He always said life was good here and it was up to us to make the best use of the opportunities given,’’ says Karnail, 61.

Amar is a third-generation cop as his maternal grandfather, Bachan Singh, was a constable in the police force too. Bachan journeyed to Malaya as a teenager in the early 1900s. He served in among other places, Kuala Kubu Baru, Kuala Lipis and Raub, where Amar’s mother was born. Bachan retired in Klang in the 1940s.

Amar says Ishar was a strict parent who emphasised studies as he believed it was the only way for his children to improve their prospects. His strictness paid off as all Amar’s siblings – three sisters and Karnail – graduated from Universiti Malaya (UM). Amar’s sisters became teachers while Karnail retired from the Customs Department. In addition to his B.Sc from UM, Amar also has an LLB from the University of Buckingham, Britain, as well as a Certificate in Legal Practice. He also graduated with a Master’s in Criminal Justice from UM, and a Diploma in Syariah Law and Practice from the International Islamic University Malaysia.

Amar, 54, never really aspired to a life in uniform. After graduating in 1982, he was toying with the idea of doing his master’s. His father, however, advised him to apply to the police force, saying, “It will make a man out of you.”

Amar did a six-month Assistant Superintendent of Police training stint at Pulapol (Police Training Centre) in Jalan Semarak, Kuala Lumpur, in 1983.

He was the only Sikh in his batch of 19 trainees. The training was tough and Amar sometimes wondered what he was doing there.

Something his uncle, Corp Basant Singh, told him spurred Amar to stay on. He said in Punjabi: “Those salutes that your father and I have given (as rank and file policemen), collect them all back (once you are an officer).”

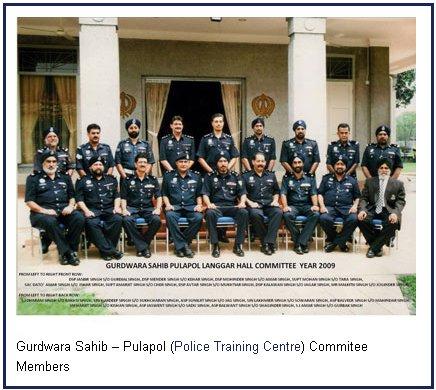

Amar’s first posting was to his hometown in Ipoh in the crime unit and he has had stints in Johor Baru and Klang. His last posting before his present position as Deputy KL CPO was as the 40th and only Sikh commandant of Pulapol from 2007 to 2010. As head, Amar made it compulsory that all trainee officers go to their respective places of worship everyday.

Amar’s first posting was to his hometown in Ipoh in the crime unit and he has had stints in Johor Baru and Klang. His last posting before his present position as Deputy KL CPO was as the 40th and only Sikh commandant of Pulapol from 2007 to 2010. As head, Amar made it compulsory that all trainee officers go to their respective places of worship everyday.

“Spiritual guidance is key to building character,” he states.

Amar also insisted that all Sikh trainees tied a turban when performing their religious obligations at the Pulapol Gurdwara as “this makes you proud of who and what you are.”

Amar says he misses his operational days now that he is in management, including investigating crimes like murder. One of the cases when he headed the Criminal Investigation Department in Klang was the discovery of Mona Fandey’s first victim.

“We found a foot floating in Port Klang. Later, we found the torso and limbs too but without a head. It turned out she was a prostitute who had been killed after seeing Mona Fandey for a black magic ritual.” (Mona Fandey was a bomoh who murdered Batu Talam state assemblyman Datuk Mazlan Idris in 1993. Mona, her husband Mohamad Nor Affandi Abdul Rahman and their assistant Juraimi Hassan were found guilty and hanged in 2001).

Amar also found himself in the middle of a crime scene while off duty in Klang.

“I was driving on the first day of Hari Raya in 1994 when I saw a Mercedes-Benz swerve in front of me and crash into a divider. The driver had been shot in the face and died within minutes.”

In any murder case, he says, you need to start with a motive and work backwards. Investigations revealed that the murder victim was a businessman who had been shot, while driving, by a killer hired by his two business partners. They were arrested in less than a week.

Amar’s most treasured possessions are mementoes from his father and grandfather’s police days. Among the awards, citations and photographs in his 14th floor office at IPK KL is a metal plate with the words “KPL 1610” painted in white. It is his father’s staff number.

“Those days, it was common to call a policeman by his number and not his name. My siblings and I were known as ‘anak 1610’. My father’s police number would be nailed to the police quarters every time we shifted house.”

Amar is more attached to his father’s police number than his own, which is 10305. All his cars bear the number as do his telephone numbers. He has even nailed `KPL 1610’ to his house in Klang.

Another heirloom are two rattan canes which belonged to his grandfather, Bachan, with the initials F.M.S., which stand for the Federated Malay States. He also wears his grandfather’s dog tag with the words “SIKH” and his police number “2023” engraved, on a chain around his neck.

As a senior assistant commissioner, Amar is the highest-ranking officer among the 279 Sikhs currently serving in the Royal Malaysia Police.

As a senior assistant commissioner, Amar is the highest-ranking officer among the 279 Sikhs currently serving in the Royal Malaysia Police.

“For a small community, Sikhs have done very well. From policemen, watchmen and bullock cart drivers, many are now graduates and professionals. We have progressed because our parents were very strict with us and brought us up with the right values,’’ he says.

On how policing has changed, Amar says, “in the 50s and 60s, policemen would go on their bicycle beat and everyone knew them. Now, it is more challenging as public expectations are higher. Another challenge is dealing with the perception that crime is on the rise.

“The figures show that crime in KL has actually dropped but the perception is that crime is up. A crime can go viral and gets repeated many times on the net or through SMS.”

The police force in the 21st century is vastly different, thanks to information technology.

“Before, investigation papers and documents were in manual form. Now the Police Reporting System is fully online. Everything is in a database so it is easier to access reports and witness statements.”

There has also been progress in the quality and speed of investigations, as well as response time. More graduates have also entered the police force.

Despite his pride in being a third generation cop, it looks like there will be no fourth generation. None of Amar’s three sons by his wife Raj Kaur, a teacher, plan to follow in their father’s footsteps. The eldest, Harpreet Singh, 19, is doing medicine, Harprem Singh, 18, plans to do accountancy after his A-levels while Anilprem Singh, 15, who is in Form Four, has set his sights on actuarial science.

Amar is philosophical about this, realising that with the Sikhs’ better socio-economic standing, more options are now available to them. He, however, has no regrets about the choice he made.

“I believe being a policeman has made me a much better person. I have met people from all walks of life and it has taught me about human nature.”

Like most Sikhs here, Amar still keeps in touch with his relatives in Punjab and has visited his father’s village several times. All his first cousins still make a living as farmers, illustrating how truly life-changing Ishar’s decision to leave over 70 years ago was.

Courtesy of www.thestar.com.my