A recently posted essay by I.J. Singh titled A Very Human Tragedy was a case report

of a Granthi at a Gurdwara caught in a vortex – a psychologically downward

spiral of loneliness, depression, alcohol abuse and hopelessness – so severe that

he committed suicide.

A recently posted essay by I.J. Singh titled A Very Human Tragedy was a case report

of a Granthi at a Gurdwara caught in a vortex – a psychologically downward

spiral of loneliness, depression, alcohol abuse and hopelessness – so severe that

he committed suicide.

Not surprisingly, the essay attracted a good deal of attention within the community and a fair number of comments, many of which were quite thoughtful. Obviously there is much more to be said on the matter.

In this collaborative attempt amongst the three of us, we will draw upon the comments of many readers of the earlier essay to formulate our opinions. They will remain unnamed since our interpretations integrate their views in ways that may not be easily ascribed to any one person.

Sikhs have been in North America for over a century. Our first Gurdwara dates from 1906. Now there are over 200 Gurdwaras in North America, most of them founded in the past 40-45 years.

The issues surrounding Gurdwara Granthis - their recruitment, selection and appointment as well as their on-the-job working conditions - are rife with matters of both management and human concern. The challenge is to find a solution so that the community gets its money’s worth and the Granthis find fulfillment and satisfaction in their employment.

Unquestionably, a Granthi’s job (if we can be clear on what it should be) is very different from other jobs that we engage in to put food on the table, and this only adds to the challenge. But it is a necessity that can’t be swept aside.

True, we have not formally surveyed Gurdwaras in the diaspora about their practices and expectations regarding a Granthi. But based on our own experience, along with anecdotal evidence, we believe that a minuscule minority (if any at all) has in place a written, legally sound and enforceable contract between the Granthi and the Gurdwara.

In fact, we are currently aware of only one Gurdwara, in Columbus Ohio, where such a contract is being negotiated and perhaps another one - in North America that has a written contract and job description specifying the expectations of both employee and employer; conditions of employment, issues of remuneration, vacation, and related issues between the Granthi and Gurdwara management.

These are normally standard provisions for any kind of employment anywhere.

Before we run too far with this, keep in mind that Granthis are not clergy (priests) and have no inherent ecclesiastical authority. But we seem to be creating a class that approximates priesthood, for which there is no provision in Sikhi. Let not Granthis morph into the new Brahmins despite clear Sikh teaching that admits no middleman between God or Guru and the Sikh.

With that said, the logical question is: do we need Granthis in the first place?

Ideally a Gurdwara, that is, a training ground for a Sikh, should be self-managed by volunteers from the sangat. This is how individual Sikhs connect to the fundamentals of their faith as well as hone their skills of collaboration with each other for a bigger cause. That is how true kinship and community develop.

But we must also recognize that Granthis are an organizational necessity in today’s world.

How, then, to define their role?

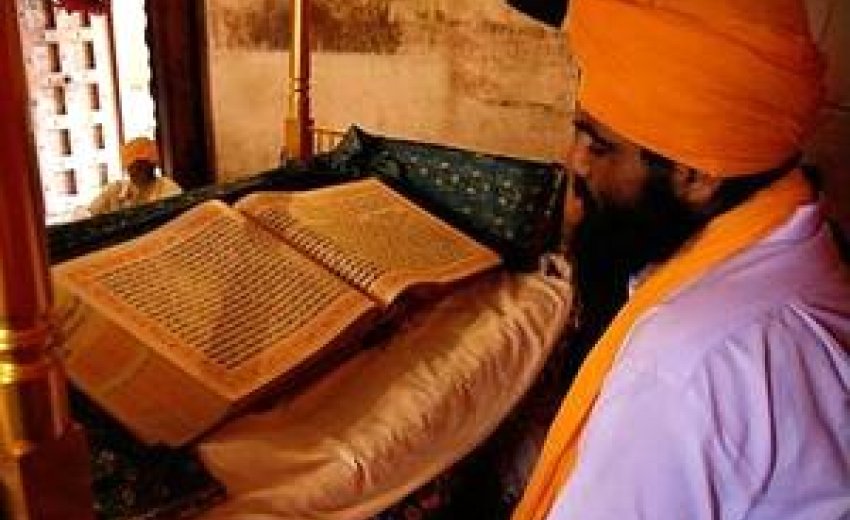

Are Granthis mere employees, a class of people who function as caretakers of Gurdwaras and the Granth? Or are they, in fact, as we would like to see them? i.e., Granthi as a curator or scholar of the Guru Granth and a teacher of the Sikh worldview, playing a larger role than one who serves at the whims of the Gurdwara management committee, and remains at their back and call.

Let’s examine briefly the current relational dynamic between Granthi, sangat and management committee.

Granthis in most North American Gurdwaras are overwhelmingly Punjab-based, that is, they come directly from Punjab. Many, but not all, are reasonably well schooled in the Guru Granth and related Sikh literature and adept in Indian mythological lore as well – with varying degrees of competence in Punjabi and Gurmukhi, and on occasion, a few other Indic languages and traditions.

Such qualifications and skills are probably sufficient to serve the newly arriving immigrant community of Punjabi origin. And indeed, Granthis fulfill an emotional and cultural need for large segments of the sangat.

But being largely Punjab-based, Granthis also bring cultural baggage that does not always resonate with sections of the sangat. We have surging populations of young Sikh men and women either born or largely reared outside Punjab and India. Their primary culture is less Punjabi/Indian and more American/Canadian/British/Australian – or any of a variety of additional possibilities.

The mélange of languages that the youth command may have widely varying levels of Punjabi intermixed with their local argot. Significant and overwhelming parts of their lives are spent outside the Punjabi cultural ambit. Interfaith issues impact them on a daily basis, at work or at play.

This reality tells us that we need Granthis who are equally adept in Western societies; knowing their values, the Judeo-Christian traditions, as well as the language and culture of the countries in which we have created our presence.

We need to evolve a new professional approach to the matter, one that is sorely lacking at this time.

Management Committees, on the other hand, bring their own cultural and feudal baggage rooted in Indian norms. This is best reflected in current hiring practices as well as the master-servant model that prevails once a Granthi is hired. When Management Committees appoint a Granthi, chances are that there is no job description. If there is one, it might describe the role of a person who is a scholar, at least on Sikhi, and who is somewhat knowledgeable about the faiths of our neighbors.

The first requirement is often partially met, the second almost never.

The reality is that Granthis are reduced to survival wages and their role can at best be described as gofers at the mercy of management committees and hardly ever as mentors and scholars in their (chosen?) profession.

Given the constraints under which Gurdwaras operate and the marginally adequate background that many Granthis bring, what exactly should the elements of a social and employment contract with the Granthi be?

In appointing Granthis, the main provisions that need and deserve our close scrutiny are:

- A written agreement formally accepted by both employer and employee.

- Educational qualifications and professional experience as well as language skills of the country where posted, etc.

- Duration of Employment

- Probationary Period.

- Remuneration – weekly, monthly, yearly or some other clearly specified time span.

- Periodic adjustments to compensation as per changes in the Consumer Price Index

- Payments and Deductions for Income Tax or other payroll taxes, as per local laws.

- Number of hours: fixed/flexible/daily / weekly services as prescribed or feasible (when they may or may not exceed 40 hours.)

- Entitlements on the death of the employee and a severance package at termination of employment.

- Eligibility for return airfare to country of origin.

- Annual holiday leave including weekly off periods.

- Policy on paid vacation and sick leave.

- Education of children under 18 years of age (high school graduation?)

- Boarding & Lodging – residential accommodation including utilities.

- Medical and dental expenses.

- Additional income from Akhand Paath, Ardaas, functions and specially sponsored programs that are held within or outside of the Gurdwara premises.

- A sabbatical every seventh year. (Not uncommon for scholars in academia.)

These issues are largely self-evident. Most of us are familiar with how the world of independent contractors and employer-employee relationships works. And, of course, laws and conventions exist in every nation, and even in the smallest levels of communities, to guide us. That’s where the controlling legal authority would rest.

A major caveat is that none of us three authors of this paper is a lawyer. But the time for lawyers will come later. Now is the time to try and define exactly what we think our community needs and exactly what is available out there. First we should construct a framework that the lawyers will later parse.

At a minimum, such an Agreement establishes equality in the eyes of the law and will help educate Management Committees to shed some of their cultural mindset. It also ensures that an equitable contract will meet the basic needs of a Granthi.

Before we examine possible solutions it would be important to understand the extent and the substance of the problems in the diaspora. A recommended first step in this direction would be to gather Granthi Data. This could be done by surveying the over 200 Gurdwaras that exist just in North America today. The survey could gather data concerning numbers, qualifications, skills, current roles, and employment agreements. Requirements from the perspective of the Granthis could also be gathered.

A well-defined employment agreement would then be the next logical step in establishing a clear and equal relationship in the nexus of the management, sangat and Granthi.

The other requirement – a Granthi as a scholar who is equally versed in the mores of the West – is a long-term issue that will require more sustained planning.

In other words, the question is how we go about balancing the Granthis’ worldly material needs and desired spiritual leadership with our needs as a community and as individual Sikhs finding our way in and around the teachings, traditions and history of Sikhi.

There are a couple of steps that we can pursue and they must run in tandem.

An obvious suggestion is to develop an academy to train Granthis with an expanded curriculum for our needs of today and tomorrow. But that will take time and resources. Yet, this process should start yesterday.

In the meantime while we await the new breed of Granthis, we have no choice but to continue with the Granthis that we have but to supplement them with part-time associate Granthis who can span the cultural and linguistic divide comfortably.

Where are we going to find such people? We think this is not so easy, but it is definitely not impossible.

Our community has many Sikhs who migrated 30 to 40 years ago. Their numbers then were negligible and Gurdwaras were sparse. Faced with the challenge of having to explain their faith they self-learned the fundamentals of Sikhi and how to interact with non-Sikhs in the wider world.

Hiring this group of people or requesting them to come and work as associate Granthis would be a step in the right direction. Some of them are retired.This will increase their availability and give them a new lease on life. It will solidify the community. (With tongue firmly in cheek we would recommend the three authors of this essay although they are not all retired yet.)

Gurdwaras need to develop functioning libraries and useful literature. In much of North America, continuing education courses in language arts and other skills are freely available. Granthi contracts should require a Granthi to take a certain number of courses and help in the building of a library. Also, a part of the Granthi’s job is scholarly writing which he or she must do to remain the curator of the Guru Granth as well as to develop the skills to be able to participate in interfaith forums, etc. as a representative of the Sikh viewpoint.

Let us encourage and help Granthis to form an association where they can communicate and socialize with each other. Granthis need to develop a life outside the four walls of the Gurdwara. We need to acknowledge that a Granthi is not a gopher, and we cannot pay or treat him as if he is. A Granthi is the way for us to better connect with Sikhi. The existing unreal, almost toxic relationship between Granthis and Gurdwaras has to change – the sooner the better.

We recognize that in this essay we have used a broad brush to paint a large canvas. We request that our widespread communities take it seriously and add caveats, conditions and requirements as needed to formulate professional, serviceable and useful policies.

The relational dynamics between the Granthi, management and sangat need to be clearly understood and augmented. Without a strong tripod of all of these three, any Gurdwara will at best remain wobbly and dysfunctional.

We reiterate: the first step forward is to survey the existing Gurdwara Granthis across North America to amass reliable data on the Granthi-Gurdwara-sangat nexus – on existing numbers, qualifications, duties, expectations and remuneration along with other administrative policies and guidelines etc.

The Sikh Research Institute (SRI) would be ideally placed to collate such information because of their ongoing programs and activities aimed at internal development of the Sikh community, and also because they have an embryonic initiative in place that focuses on education and development of Granthis in the diaspora. (Full disclosure: Two of us, IJS and RS, are closely affiliated with the activities of the SRI.)

After that will be the time to bring out a coherent and well-defined Employment agreement that will provide us some minimal standards in qualifications and expectations.

For starters explore the “Granthi Training Initiative” of the Sikh Research Institute.

June 28, 2012